Gun seizures more likely under Colorado's Red Flag if law enforcement is involved

Red flag applications are approved 95% of the time if police step in. If Coloradans file on their own, the approval rate dips to 32%.

Colorado’s 2-year-old “red flag” law gives police officers and average citizens alike the power to seek the removal of guns from people they believe are dangerous – but a 9Wants to Know investigation found the chances that will actually happen depend largely on who’s asking.

The law took effect on Jan. 1, 2020, and it gives judges the power to issue what’s known as an “extreme risk protection order” if there’s compelling evidence that an individual poses a danger, either to themself or others. In those cases, the gun owner is required to surrender their weapons for 14 days, and the order can be extended to 364 days.

The goal of the law is simple: to temporarily remove guns from someone in crisis who hasn’t broken the law.

Red flag petitions The approval rate varies greatly depending on who makes the request.

A monthslong 9Wants to Know analysis of every single red flag petition filed in Colorado during the first two years the law was on the books found that judges approved 95% of the petitions filed by police officers – but a little less than a third of those sought by average citizens.

And in El Paso County – where the sheriff has publicly said he won’t enforce the law unless a crime is involved – the success rate is tied for the lowest approval rate among Front Range counties. Judges in El Paso County approved about one in five red flag petitions in 2020 and 2021.

Graphic created by Zack Newman.

The 9Wants to Know investigation, which included an examination and analysis of every single red flag petition, provided a detailed look at how the law has worked during its first two years of existence.

Graphic created by Janet Oravetz.

Of the 244 unique red flag petitions that were filed, 146 were granted. That’s an approval rate of 60% – significantly lower than the bill's fiscal note prediction before the law took effect that 95% of the petitions would be granted.

Of the 107 petitions filed by law enforcement officers, 101 – or 95% – were granted. But of the rest, which were filed by citizens, about 32% were approved.

While the approval rate in El Paso County stood at 20%, judges granted 65% of the petitions filed in neighboring Douglas County. And in Denver, where more than half of the petitions were filed by police, 79% were approved.

One case that unfolded in El Paso County in 2021 provides a snapshot of how the law can work.

A success story 'This is a step to helping him get better.'

A woman named Christine became frightened and then frustrated as her brother struggled with mental health issues and alcohol – and made suicidal threats.

9NEWS agreed not to use Christine's last name or identify her brother.

One night last fall, she called 911. Her brother was drunk, and he’d been in a FaceTime conversation with a friend and during it had put his gun in his mouth. Responding officers ultimately concluded that he was not a threat to anyone else and decided to let him sleep it off and check on him the next day.

When the next day came, a police officer called Christine and suggested that she file for a red flag order. She wasn’t sure what her chances of success would be but went ahead anyway.

“I felt like at that point I was kind of in the mindset of even if it doesn't go through, at least I tried,” she said.

Read her application below.

She went to court with a binder of evidence – including statements from a friend and her brother’s ex-wife and text messages from her brother. In one message, he wrote: “I swear to God, if one f------ cop shows up, there's going to be a standoff with your niece and nephew in the house .. so don't even try that bulls---.”

“I told the judge 100 times, you know, I know who he can be, and he's not himself right now,” Christine said. “I just want him to get better. And I think this is a step to helping him get better, is not giving him that opportunity to get chaotic with weapons.”

The judge granted the petition. Her brother surrendered his guns to their mother, who sold them.

Need for change An ambush of deputies in late 2017 spurred conversations and then change.

The law was championed by two Colorado sheriffs on opposite sides politically – Republican Tony Spurlock of Douglas County and Democrat Joe Pelle of Boulder County.

“There's no room for politics in people's lives or saving people's lives,” Spurlock said. “And that's what this sliver of law is about is saving people's lives.”

Both men were affected deeply by the same incident – a shooting on Dec. 31, 2017. That morning, a man with mental health issues and guns opened fire on Douglas County deputies. Deputy Zackari Parrish died, and four other officers were wounded. One of them was Pelle’s son.

“This became a special interest to me on a personal level, and a professional level,” Pelle said.

The family of the shooter had tried unsuccessfully to take his guns away from him, a source of great frustration for Spurlock.

“I think about Deputy Zack Parrish every day and I think about that very early morning,” Spurlock said. “I think about what could we have done in the front to prevent such a tragedy. … There wasn’t anything that anybody could do a lot about him having access to guns.”

The law, which was named in Parrish’s memory, allows police officers, family members, and roommates to seek a red flag order and requires them to go to a judge with a detailed petition laying out the reasons one should be granted and providing information about the person’s access to weapons.

Petition patterns There's a high bar for approval.

9Wants to Know observed a pattern in the red flag applications that were approved. They were all highly detailed and outlined a clear threat. Pelle said there’s a high bar for approval to make sure the law is not being misused to take guns away unnecessarily.

“It's a bit onerous,” Pelle said. “You have to go through a lot of hoops in order to get one of these. But it's there and it's available. And I think – and you have the data – but I think statistically it's fairly well proven that it's not being abused.”

However, there were other detailed petitions written by citizens that outlined a clear and present threat that were not approved for unclear reasons. In multiple cases, people dealing with domestic abuse pleaded with the court to take away the weapons but were denied.

Below is an example of a denied petition. It was requested by a resident of Pueblo County.

Those approved are often written like an incident report typically compiled by law enforcement. Christine said she thinks her binder made a difference in convincing a judge to grant her petition.

“I mean, I walked into court with a binder,” she said. “I put everything out there that I had that made me feel, you know, that he shouldn't be around weapons.”

Christine said it was intimidating to not be an attorney and go up against her brother’s court-appointed lawyer. Her advice for others in a similar position is to try to get the red flag order. This way, you know you did everything you could.

“Don't give up just because you think you're not going to get it,” she said. “If you don't ask for it, there's no chance of you getting it.”

Below is an example of an approved petition which was requested by a detective with the Aurora Police Department.

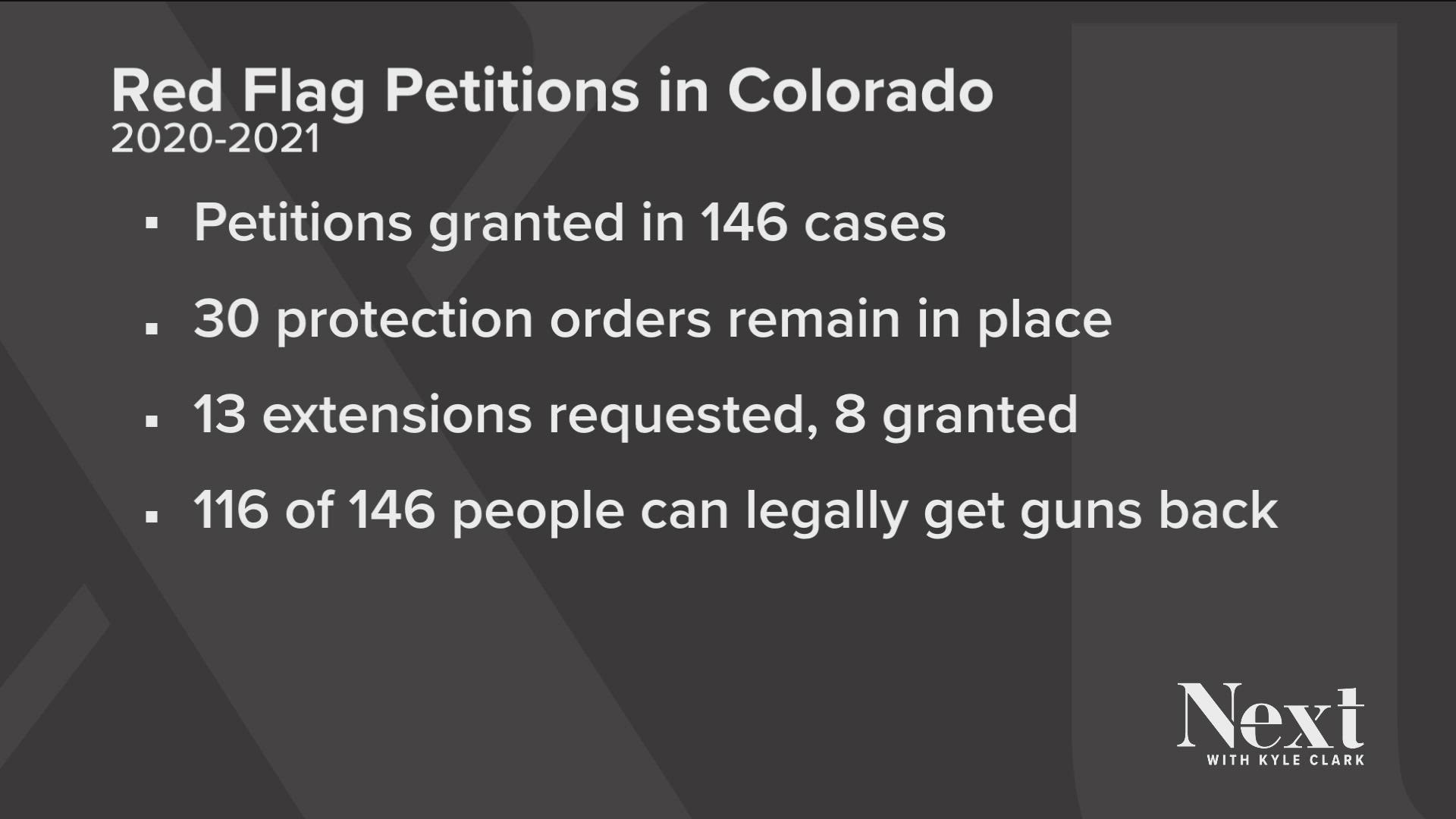

9Wants to Know looked at all the red flag petitions filed in the first two years of the law and found that judges granted them in 146 cases – some for 14 days and some for 364 days (both options are allowed under the law). We found that as of Wednesday, 30 of those extreme risk protection orders from 2020 and 2021 remain in effect – either because they haven’t yet expired, or they expired and were renewed by a judge for another 364 days.

The orders are extended only in rare cases – they were requested 13 times, granted eight times. But, 92% of those renewal applications happened in cases with law enforcement involvement.

All of the approved renewals came from police.

The bottom line: After Wednesday, 116 of the 146 people who were ordered to give up their guns can legally get them.

See the process behind our data analysis on our GitHub here.

Reach investigative reporter Zack Newman through his phone at 303-548-9044. You can also call or text securely on Signal through that same number. Email: zack.newman@9news.com. Call or text is preferred over email.

Contact 9Wants to Know investigator Kevin Vaughan with tips about this or any story: kevin.vaughan@9news.com or 303-871-1862.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Investigations & Crime