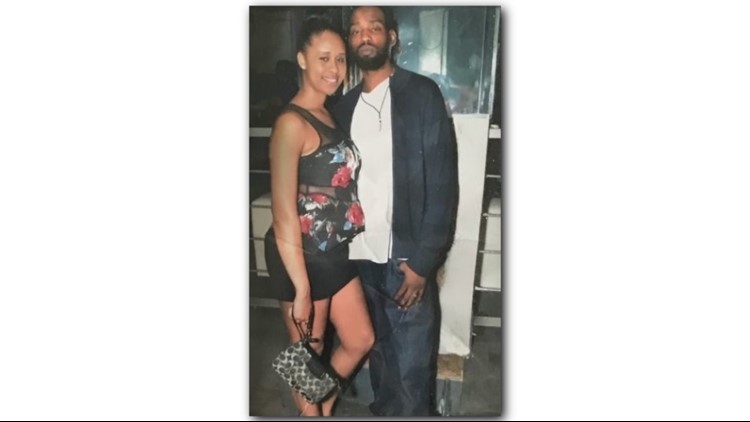

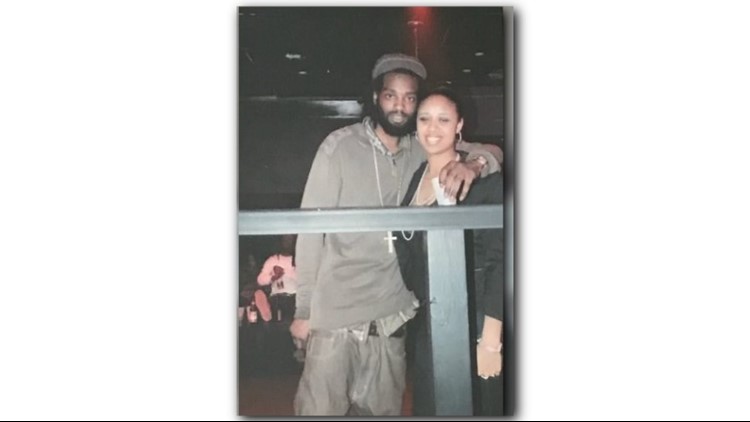

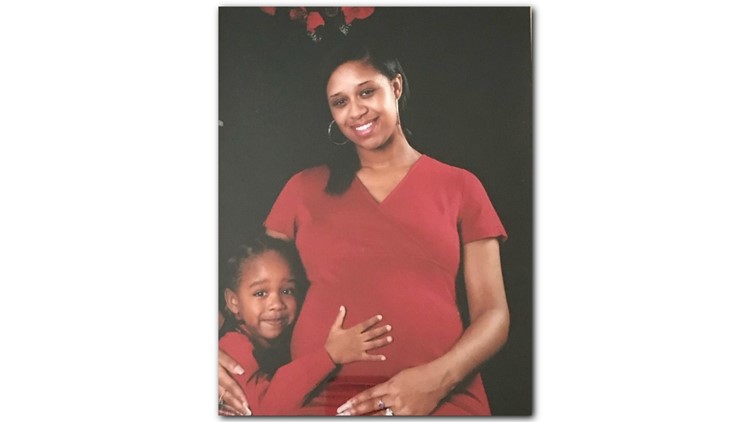

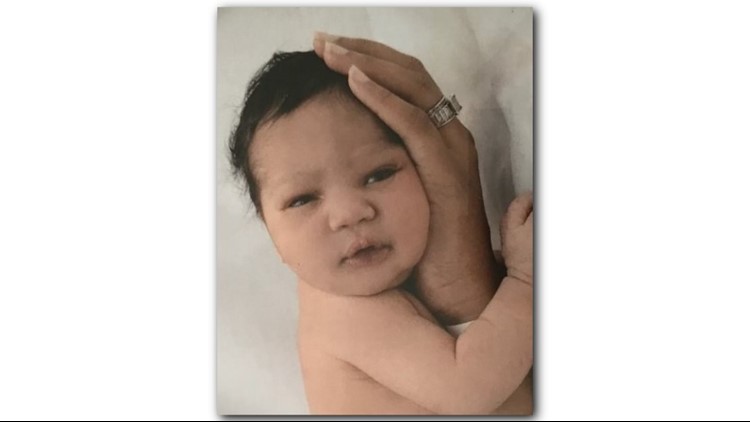

Ayanna Smith gave birth to her third son at 1:05 a.m. on New Year’s Day. Little did she know, one of her happiest moments would turn into one of her scariest.

“Shortly after he came out, I remember feeling extremely dizzy," Smith said. "It got extremely bright, and I saw stars everywhere. I just remember them placing him on me. I just told them, 'I can't move. I couldn't move anything.'"

Her mother, Sandra Smith, recalled the horror of watching from the delivery room.

“You went from this euphoria watching this little person come out," she said. "Then, all of a sudden, you just see a river of blood."

Sandra Smith watched the doctors remove her grandson from his mother’s arms. She watched her daughter turn ghostly pale; her lips were purple. That’s the moment she realized the delivery was dire.

An emergency blood transfusion helped save Ayanna’s life.

Ayanna is not alone

Ayanna Smith is one of 50,000 women each year who almost die as a result of childbirth. That’s one mother every 10 minutes in the United States.

The causes of most near-death emergencies are preventable. However, the risk of having complications is much greater for black women.

“If you are black and highly-educated, you still have a higher probability of pregnancy-related death than the least educated white woman," said Dr. William Callaghan, chief of the Maternal and Infant Health Branch at the Centers for Disease Control. "It is astonishing. The only difference is the color of one's skin."

Ayanna felt that her medical team assumed she would be like everyone else and missed the warning signs of her condition.

“If they had checked the charts, or if I had one consistent doctor, if this was one way for them to mark that this was [my] issue -- be careful of this, be mindful of it, they would've been more prepared for when I came in versus having to fix the issue after it's already happened,” she said.

Childbirth nearly killed Ayanna Smith

Some medical professionals don't agree that racism is to blame.

"We have a huge African American population of patients, and I have no doubt in my mind that we give them exact same care as anybody else," said Dr. Sujatha Reddy, a specialist in women’s health.

Some 800 mothers a year don't survive childbirth.

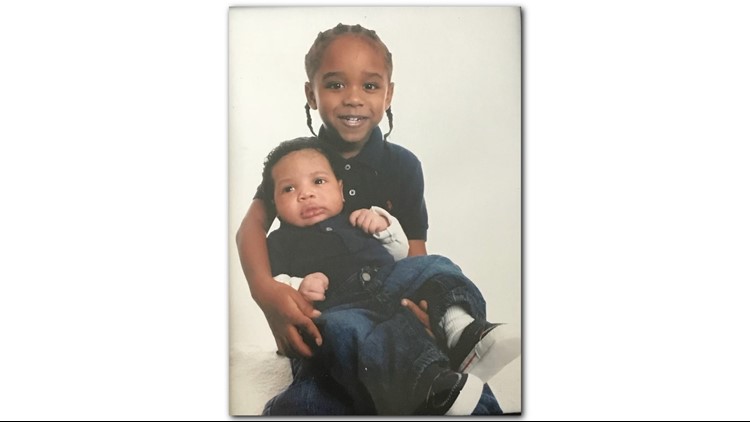

Kira Johnson was one of them. She died from a hemorrhage 12 hours after giving birth to her second son.

"When this happened to me -- when my wife passed away from a preventable cause related to childbirth, I was thinking Kira was an anomaly," said Charles Johnson, Kira's husband.

In the two years since Kira's death, Charles has learned the tragic truth.

"In a nation that's the richest, most wealthy country in the world, for this to happen is ridiculous," he said.

Losing a dream

Ayanna survived childbirth, but lost something else in the delivery room. She always dreamed of one day having a baby girl.

"She and her husband decided no, they're not going to because of what happened afterwards. That crushed me because I know my daughter wants a daughter and to know that she won't go through it because of this…it’s not fair," Ayanna's mother Sandra said.

“I don’t want to try again,” Ayanna said. "I think it affected my husband a lot more, because I don't think he wants to see me give birth again...If we wanted a girl, I don't know if we go through that experience again."

Fighting for change

April 12 is Kira and Charles Johnson's youngest son's birthday. It will also be remembered as the day Kira died.

Charles knows one day he'll have to tell his sons how their mother died.

"I anticipate that after we have the conversation...my sons will ask me, 'Daddy, what did you do about it?" he said.

"It's important for me that I'm able to look them in the eye and say, 'Son, you know we lost but they didn't win. This is the work that we've done. This is the legacy that your mother stands for. This is why other people don't have to worry about what we've been through. And that's what's important to me."

To push for a change, Charles has spent the past year lobbying Congress to pass two bills: HR1318 and the MOMS Act.

HR 1318 directs the Department of Health and Human Services to establish programs for reviewing pregnancy-related deaths in every state called Maternal Mortality Review Committees (MMRCs).

These groups search for answers about what caused a mother’s death. They also investigate what could have prevented her from dying. This information helps create action plans seeking solutions to stop it from happening to another mother.

Under HR 1318, states would need to develop procedures for mandatory reporting to health departments.

“We can review every single death and make sure that the death of every woman counts and there is a lesson in how to improve quality," said Dr. William Callaghan. "We’ll be able to understand where things went wrong in her care."

The MOMS Act is a proposed bill that would help states and hospitals fund programs aimed at reducing pregnancy-related deaths.

Kira's mother-in-law, Judge Glenda Hatchett from the reality TV show, said she's proud of the work her son is doing.

"I know that the advocacy work that Charles is doing will save lives," she said. "That will make a difference -- there will be other families who will not know the pain that we have known, that will not have to explain to a child that his mother is never coming home, will have to explain when you say 'I want to go to heaven because I want to see my mommy.' It is...no family should go through this."

Right now, both bipartisan bills seem stalled on Capitol Hill. Charles Johnson said he won’t stop fighting.

“My philosophy is wake up, make mommy proud, repeat. That's it. And that's how I do it day by day. Day after day,” he said.

Here's a link to help find your Congress members if you would like to reach out to them about the bills.

►PREVIOUS CHAPTER: Why childbirth is a death sentence for many black moms