LOVELAND, Colo. — Less than a year before Javier Acevedo shot and killed his ex-girlfriend Lindsay Daum and her 16-year-old daughter Meadow Sinner in Loveland last summer, a court ordered Acevedo to give up any firearms in his possession.

But no one checked to make sure he did that.

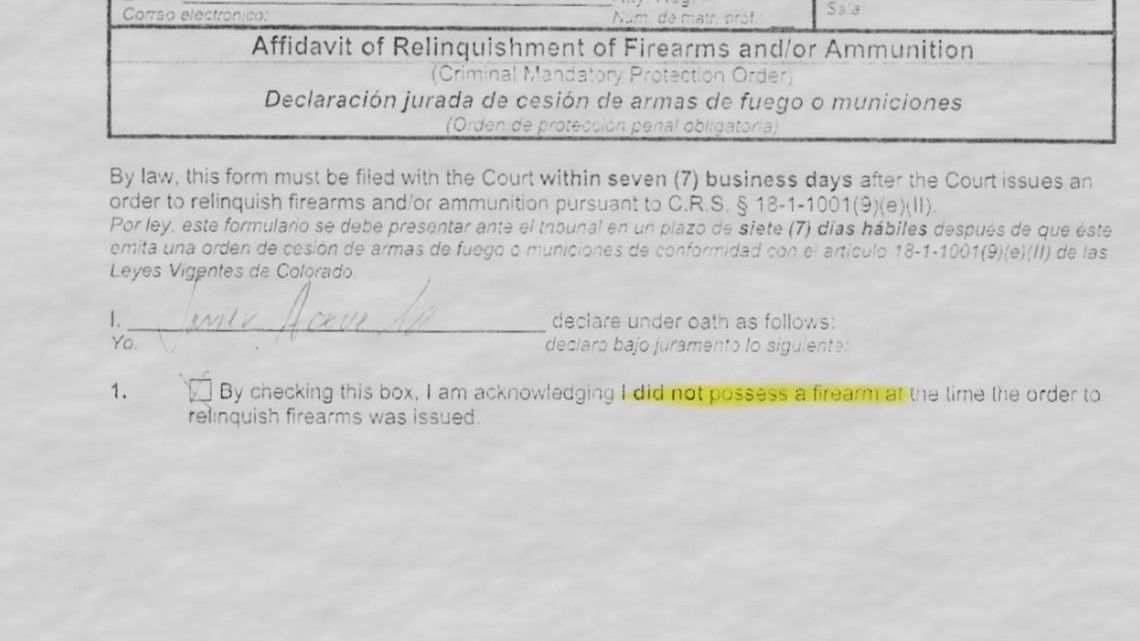

In November 2021 – eight months before the murders – a Denver County court granted a criminal protection order for Acevedo’s ex-wife. The court also ordered Acevedo to give up any guns. Court records show he checked a box saying, “I am acknowledging I did not possess a firearm at the time the order to relinquish firearms was issued.”

According to the Loveland Police Department, Acevedo legally purchased the shotgun he used to kill Daum and Sinner in March 2021, a few months before signing the firearm relinquishment form in Denver.

The case in Denver was handled by the Denver City Attorney’s Office. A spokesperson said their office doesn’t have a role in verifying the truthfulness of what is attested to on the firearm relinquishment form, and police lack probable cause to get a search warrant to look for a gun based off a protection order alone. Law enforcement, however, can get a search warrant if the person filing the restraining order specifically says the person has access to guns, according to the spokesperson.

The Denver Police Department said their records don’t show a search warrant was served against Acevedo.

“Unless someone is to say you are lying on that form or committing perjury, there is really no way to enforce that,” said Katie Wolf, the public policy director for Violence Free Colorado.

Wolf works with lawmakers on bills related to domestic violence. She said Denver sees more than 2,500 domestic violence cases at the municipal level every year, so it would take a lot of resources for the Denver City Attorney’s Office to investigate every single firearm relinquishment form.

Garin Daum, the brother of Lindsay Daum, feels someone should have double-checked to make sure Acevedo didn’t have a gun when he signed the firearm relinquishment form.

“Absolutely, that process should change. That is so clear. It is just incredible,” he said. “The fact they are like, oh just sign here – you are already in enough trouble. Just check this little box to say you don’t have guns.”

The Denver District Attorney's Office, which handles misdemeanors and felonies, does double check statements made on these forms. This office said it's the only jurisdiction in Colorado -- and one of only a few in the country -- that has a dedicated domestic violence firearms relinquishment investigator.

This person even reviews forms where the domestic violence defendant has said he or she doesn't possess a gun at the time, according to DA's office spokesperson Carolyn Tyler.

"As part of the DA’s Domestic Violence Initiative, DA McCann hired a firearms relinquishment investigator to work closely with our senior prosecutor and victim advocates," Tyler said. "Removing firearms as soon as a victim seeks help is critical, because a domestic violence victim is five times more likely to be killed if their abuser has access to a gun. In 2022, that investigator had a total of 114 firearms relinquished from 59 defendants."

The Denver City Attorney's Office said they don't have a firearms relinquishment investigator because domestic violence crimes prosecuted in municipal courtrooms don't prompt a federal law that prohibits someone charged and convicted of domestic violence offenses from having guns.

Garin Daum, Lindsay's brother, questioned how easy it would have been to find out Acevedo had purchased a gun before signing the form.

Wolf with Violence Free Colorado knows it’s not that easy, because she said the law in Colorado doesn’t allow that type of search or database.

“It would be a lot easier if there were a way to just check to see if people had guns, if there was a database where people’s names were listed,” Wolf said. “The Colorado constitution prohibits that from happening. I think there would be a very significant debate in Colorado in whether or not that should be the case or not, but in the case of domestic violence it would absolutely be beneficial, especially in these cases, for people to know if someone has a firearm.”

By the time police found Acevedo’s gun in July 2022, it was too late. He had already killed Lindsay Daum and Meadow Sinner.

“That’s all it was,” Garin Daum said. “A meaningless piece of paper.”

Lindsay Daum filed a request for a protection order against Acevedo twice. Both times, a judge in Larimer County denied her request, stating there wasn’t enough evidence.

A month before she was killed, Lindsay Daum told a judge Acevedo called her and threatened to kill her. Acevedo was also facing multiple felony charges, including sexual assault on a child.

After all of this, Garin Daum feels guilty he put so much trust in the system.

“This is one of the biggest pieces of guilt that I live with right now,” he said. “I didn’t do more, and I was like – hey, obviously you are going to get a day in court. I literally had faith in the legal system to protect her.”

“He said he had killed her and he was going to kill himself”

On July 28, 2022, Lindsay Daum’s boyfriend called 911. He told police Acevedo called him from Lindsay’s phone to say he had just killed her and was going to kill himself.

Dispatch also received 911 calls from other children in the house.

Officers responded to the home on Pavo Court in Loveland. They found Lindsay Daum and Meadow had been shot multiple times.

“[Lindsay] was a fairly private person, but her children were her life. That is what she did, like all she ever wanted to do was be a mother,” Garin Daum said.

“Meadow was sort of the polar opposite of her mother in a lot of ways,” Garin Daum said. “She was very social, very outgoing. She was involved in theater.”

Investigators from several agencies quickly started a manhunt to find Acevedo. Through a combination of phone ping searches, 911 calls from witnesses and help from the Denver Police Department’s helicopter, police found Acevedo in an open space in Erie later that day. He was holding the shotgun he used to kill Lindsay and Meadow.

Acevedo eventually shot and killed himself. A report from Loveland Police said Acevedo’s toxicology results showed a very significant amount of methamphetamine in his blood. He was also wearing the GPS ankle monitor issued in the Denver County case.

Two days before the murders, Loveland Police got a call from a concerned citizen that alleged Acevedo made a statement to them about killing his wife. Loveland Police said this was investigated and the department didn’t find probable cause for any criminal violation.

Legislation in the works

When Lindsay Daum requested a protection order a second time in Larimer County, Acevedo was facing multiple felony charges there.

A Denver County court had also placed Acevedo on intensive supervised release with a GPS ankle monitor because of the protection order issued for his ex-wife in November 2021.

Despite this, a judge in Larimer County denied Lindsay Daum’s request for a protection order. The judge said there wasn’t enough evidence to support one.

The case in Denver County was handled at the municipal level. Wolf said municipal cases are not in the same system as other courts. That means, according to Wolf, a judge reviewing someone’s background might not know he or she had a protection order in another city at the municipal level.

Wolf is currently working on a bill with state lawmakers to change that. She believes there needs to be a better way for judges to learn about cases in other areas.

“It’s really important when we talk about habitual offenders, when someone is offending more than one time, because they are more likely to if they have offended in the past,” Wolf said.

Wolf thinks the state needs to do a better job of letting domestic violence victims and survivors know who they can talk to if they disagree with someone’s statements on a firearm relinquishment form.

“I think at this point with the way the laws are right now that we need to do a better job educating victims and survivors that they are able to talk to the district attorney, to the judge, to let them know they disagree, that they know that person possesses firearms, and then they are able to trigger further action that is currently permitted by law," she said.

Resources

Below is a list of resources for victims and survivors of domestic violence.

- Crisis Center 303-688-1094 / Crisis Line 303-688-8484

- Family Tree 303-422-2133 / Crisis Line 303-420-6752

- Gateway Domestic Violence Services 303-343-1856 / Crisis Line 303-343-1851

- SafeHouse Denver 303-318-9959 / Crisis Line 303-318-9989

- Rose Andom Center 720-337-4400

- Project SafeGuard and Legal Advocacy

- Servicios de la Raza 303-458-5851

- The Initiative 303-839-5510

- National Domestic Violence Hotline 1-800-799-7233 / TTY 1-800-787-3224

- DOVE TTY/Voice 303-831-7932 / Crisis Line 303-831-7874

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Investigations & Crime