Private Guards, No Oversight, a Pattern of Rape

Nowhere to Turn: This nationwide investigation exposes widespread sexual assault by private contractors transporting inmates and pre-trial detainees.

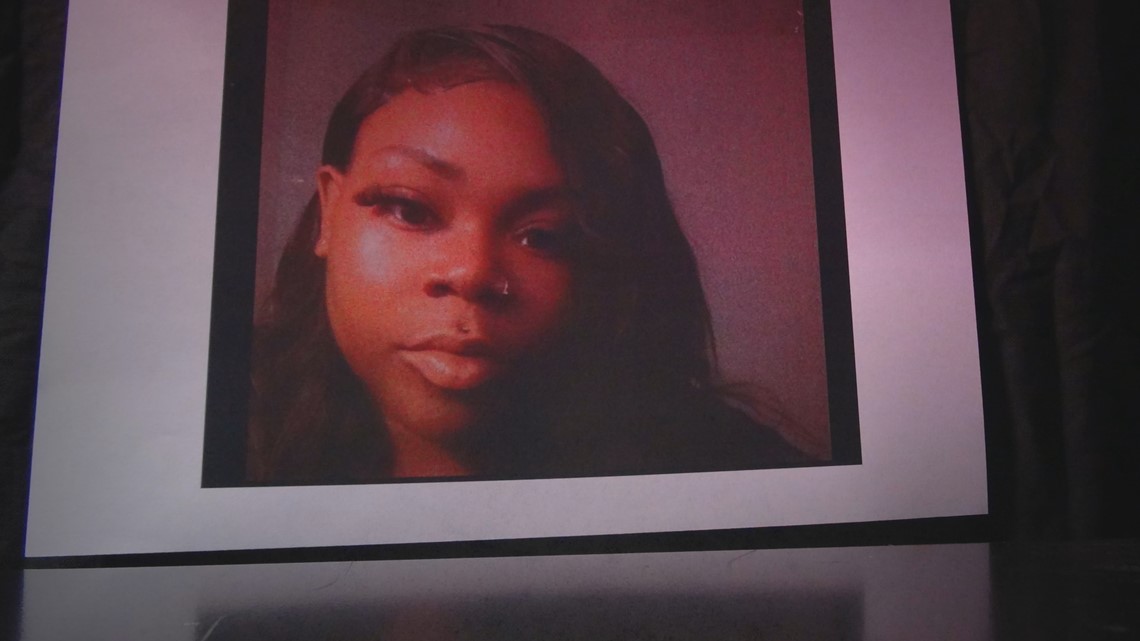

In June of 2019, Danielle Sivels was living in Texas when she was arrested on an out-of-state warrant for probation violations stemming from a 2015 hit-and-run.

Danielle, 34 at the time, battled mental illness, addiction, and grew up in and out of the foster care system surviving family violence and sexual assault as a child.

She was now set to be extradited nearly a thousand miles to Ramsey County, Minnesota.

Ramsey, like countless jurisdictions across the country, outsources its long-distance prisoner transport to private for-profit companies because it’s cheaper than making the long treks themselves.

A pair of guards from Ramsey’s contractor, Inmate Services Corporation (ISC), headquartered in West Memphis, Arkansas, picked Danielle up at the Dallas County jail.

She had been on her way to the gym when arrested and was wearing just workout leggings and a sports bra.

She was placed in handcuffs, leg shackles, and a belly chain and loaded into a white passenger van filled with other inmates, all male, for extradition to the Ramsey County jail in Saint Paul, Minnesota.

Danielle says the two-day journey was a trip through hell filled with terror, threats, and repeated sexual assaults by an ISC guard.

“It could have been prevented,” she said of the alleged assaults. “It could have all been prevented.”

Danielle is right.

KARE 11’s investigation, based on a review of thousands of court documents, contracts, federal records, media reports, and interviews with former guards, detainees, and attorneys finds ignored warnings, legal loopholes, and broken promises.

The result: a nationwide failure to provide oversight of the private prisoner transport industry that has fueled a systemic pattern of rape and abuse.

Editor’s Note: KARE 11 does not identify victim-survivors of sexual assault without their consent. In some cases, only initials or a first name are used to protect their privacy.

Chapter 1 The Predator and the Prey

The van carrying Danielle pulled into a truck stop in Oklahoma.

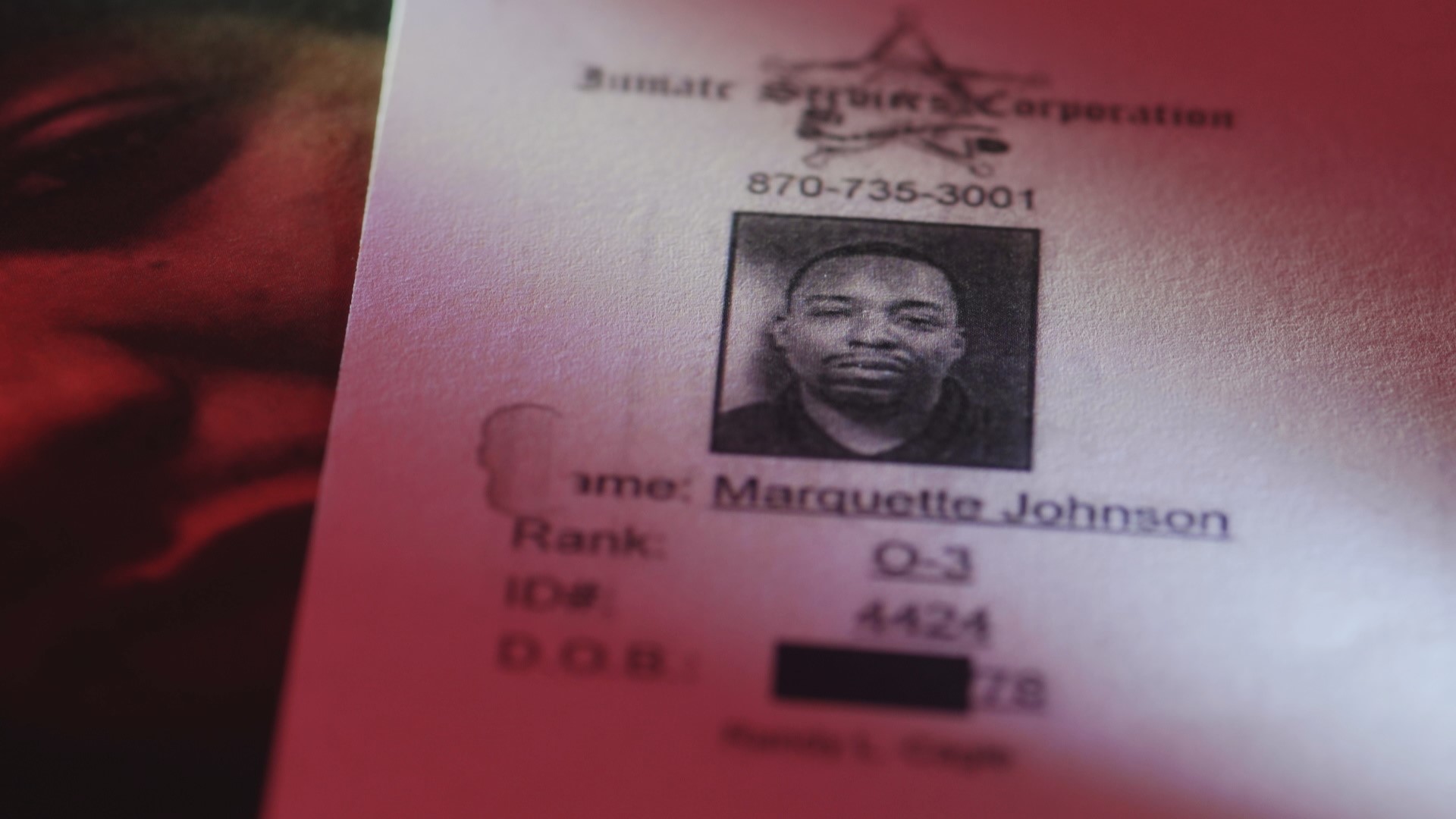

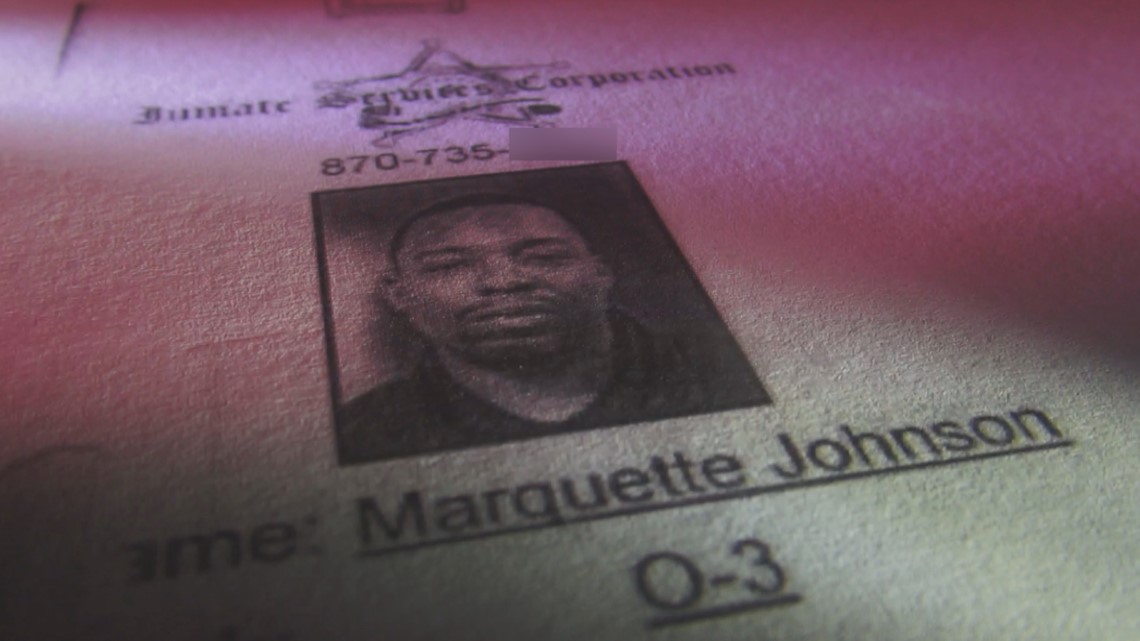

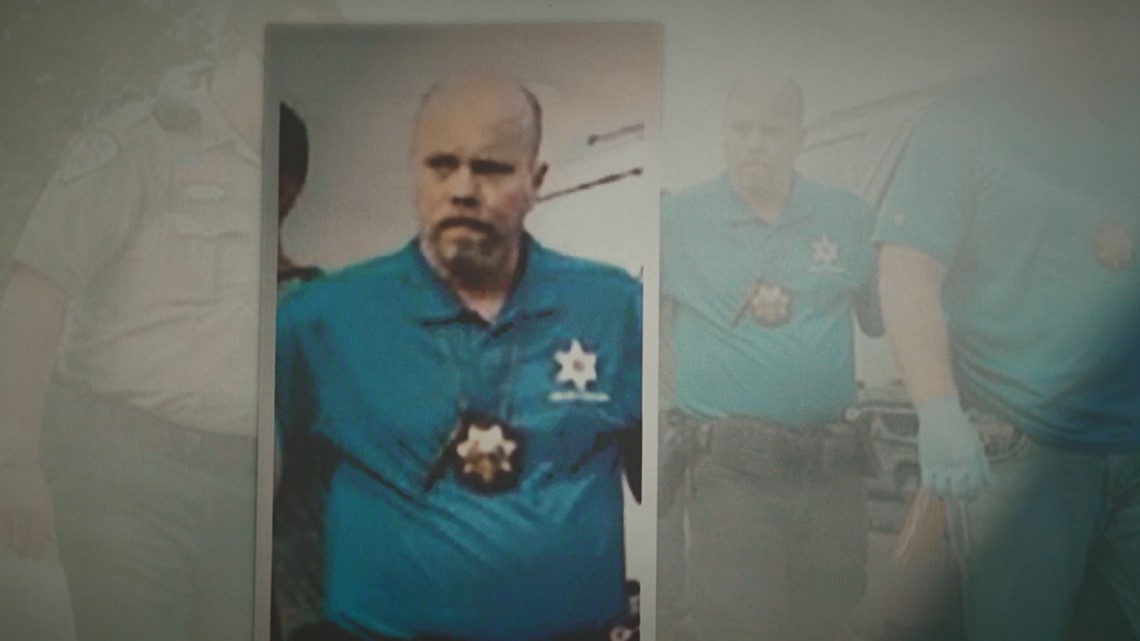

One of the guards, Marquet Johnson, 44, asked her if she needed to use the bathroom.

According to a lawsuit filed in U.S. District Court this year by Danielle and her attorneys, Johnson walked her inside with her hands cuffed behind her back, followed her into the stall and stood facing her as she sat on the toilet.

She says the guard then unzipped his pants, exposed himself and demanded oral sex, forcefully pushing her head down. Danielle says Johnson had a gun, and she had no choice.

“I’m handcuffed, I’m in a bathroom stall,” Danielle said. “He was a predator, and I was the prey.”

That was just the beginning.

After that first sexual assault, Danielle says she was subjected to bizarre mind games and intimidation.

She describes Johnson taking her handcuffs off and having her sit directly behind him in the van, placing her arms around his waist as he drove, which left her hand resting directly on his gun.

She says Johnson’s partner woke up, saw her hand resting on Johnson’s gun and looked shocked, but said nothing.

Both the federal statute providing standards for private prisoner transport companies and Ramsey County’s contract with ISC called for a female guard to be present during the transport of a female inmate.

But that mandate was not followed by ISC or enforced by Ramsey County. Records KARE 11 reviewed for this and numerous other transports of female inmates by ISC show there were often just two male guards.

“There really is no oversight,” said Paul Applebaum, one of the attorneys representing Danielle in her lawsuit which accuses Ramsey County of deliberate indifference to their duty to screen private vendors tasked with transporting inmates.

“So, I’m not surprised in the least that this is what’s being uncovered by people like yourself who are digging this up,” Applebaum said.

As the transport van carrying Danielle approached the Iowa-Minnesota border, she says Johnson led her, once again handcuffed, into another rest stop bathroom. He followed her into the stall, and this time violently raped her over the toilet leaving her in pain and bleeding.

“I felt like a scared little girl, and I felt like there was nobody who could help me,” she recalls.

Danielle believed Johnson, who was hauling her around the country in chains, carrying a gun and a badge, was a member of law enforcement so she was afraid to say anything when dropped off at the Ramsey County jail.

She thought because of her criminal history, she would not be believed.

“That was exactly what I was afraid of,” she said as tears streamed down her face, “that’s exactly why I didn’t say anything.”

Chapter 2 Continuing Contact

Danielle kept silent about the alleged attacks as she pled guilty to the charges she was facing and was incarcerated at the Shakopee women’s prison.

However, her interaction with the man she says raped her was not over.

Marquet Johnson began contacting her via emails and phone calls at the prison. She says he pursued a relationship, acting as if the rape was not rape at all.

“He tried to make it seem like it was consensual,” she said. “He tried to make it seem like he was confused, like that’s what I wanted.”

Even if that were true, it’s impossible for an incarcerated person to consent to sex with a guard says Julie Abbate with Just Detention International, a non-profit dedicated to ending sexual abuse in confinement.

“Due to the power dynamics that the staff hold over every incarcerated person, it renders consent absolutely impossible to give,” said Abbate, a former deputy chief in the U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division.

What KARE 11’s investigation discovered, and Danielle had no way of knowing at the time, is that Marquet Johnson wrote notes to and tried to keep in contact with at least nine women he had transported as a guard for ISC.

The women all have similar stories of sexual assault.

Chapter 3 Accused Serial Rapist

Five months after Danielle’s transport, in November of 2019, Delta County, Colorado paid ISC to pick up a female detainee in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

The following account comes from federal and state court records.

Marquet Johnson and another guard picked up a woman with the initials T.P. at the Santa Fe jail.

She was loaded into a white van that held three male detainees.

About an hour into T.P.’s transport, the van stopped in Albuquerque to drop off the three men leaving her alone with the guards.

A few minutes later, around 5:50 AM, the van stopped at a gas station with an attached Carl’s Jr. restaurant.

The other guard went inside to buy breakfast and that’s when court records state Johnson ordered T.P. into the back row of the van and climbed in after her. He removed her ankle restraints, loosened her handcuffs, leaving her belly chain in place.

T.P. told the guard that she was unsure what was going on, but that she did not want “to do this.”

In response, Johnson pulled out a short black gun, and, while resting the gun on his lap, told T.P. that he wanted her to cooperate, “otherwise, it was going to get ugly.”

He then raped her while holding his gun against her cheek.

Afterward, he ordered her to quickly pull up her pants, she was still doing so when the other guard came back with the breakfast burritos.

The other guard got in the driver’s seat and Johnson stayed in the back row with T.P.

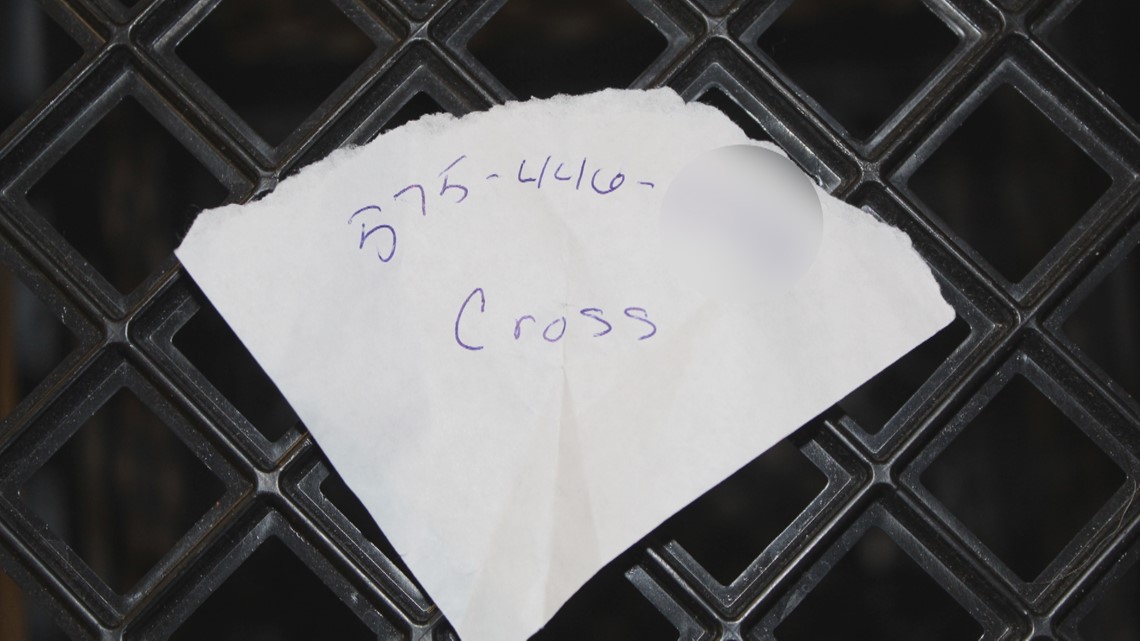

Johnson then wrote a note with his number on it and stuck it in his victim’s back pocket.

Later at another rest stop, Johnson gave the woman a bottle of soap and a washcloth and whispered for her to go clean herself in the bathroom. T.P. went into the bathroom but did not wash up, she told investigators, as she wanted to preserve evidence of the assault.

When dropped off at the Delta County Colorado jail, T.P. told the booking officer about the attack and requested a rape kit.

DNA from that rape kit was matched to Johnson after federal investigators served a search warrant on him.

The note Johnson wrote was also found in T.P.’s clothes. The number on it matched Johnson’s.

"There's not really a question whether it happened,” said T.P.’s attorney Laura Shauer Ives. She added that her client saved other women from being raped. "Absolutely my client saved a number of women from being victimized by this man."

Johnson was charged with sexually assaulting T.P.

A recent court filing indicates the two sides are working on a plea agreement and “anticipate that Defendant will enter a guilty plea in mid to late November.”

Johnson’s lawyer did not respond to a request for comment.

Chapter 4 The Search Warrant

FBI agents investigating T.P.’s case served a search warrant on ISC headquarters in West Memphis, Arkansas.

The agents were looking for evidence of other transports Johnson had done that included female detainees.

That led them to an ever-growing list of women – 15 is the latest number available in court records – who told eerily similar stories of being sexually assaulted or harassed by Johnson.

A woman with the initials W.P. provided KARE 11 with a note she says Johnson gave her after showing her his gun and sexually assaulting her in a rest stop bathroom during a transport from Sisseton, South Dakota to New Braunfels, Texas.

The phone number on it matches the note T.P. received six months later.

W.P. says Johnson also pursued a relationship with her while she was incarcerated and after she was released. She says she was at the lowest point in her life following her arrest and incarceration and rationalized away what happened just to be in a relationship with someone.

The woman tells KARE 11 that Johnson even showed up at her Colorado home while he was working, coming inside for sex, while a van full of prisoners waited in her driveway.

Dabrielle Dixon was extradited in 2019 from Chicago, Illinois to Des Moines, Iowa on charges related to writing bad checks. She had never told anyone her story of being sexually assaulted by Johnson in an Illinois rest stop bathroom until the FBI contacted her.

“The stress from it, the traumatization of it, the hurt from it is just building up when you don’t have nobody to talk to,” Dabrielle told KARE 11. “I don’t want that to happen to nobody else,” she explained as the reason she’s now publicly sharing her story.

In Minnesota, Danielle Sivels also said she had never told anyone her story of being raped until the FBI approached her asking if anything happened to her during her transport by Johnson.

When she learned there were so many other women with similar stories, she says it brought guilt.

“I feel like, if I would have said something sooner, it might have saved even just one person from experiencing what I experienced,” she said.

The FBI’s search warrant at ISC headquarters revealed that even when a woman sounded the alarm about Johnson’s behavior, his employer left him on the job transporting female detainees.

Eight months before T.P. was transported, Johnson picked up a young woman named Laura in Indianapolis, Indiana to be taken to Munfordville, Kentucky.

Laura was six months pregnant.

According to the federal criminal case against Johnson, when the van stopped at a rest stop, Johnson told the woman, “Damn, girl. I didn’t get to see you when they picked you up, but I see you now.”

After all the other detainees were dropped off, Laura was alone in the van with the guards.

Court records claim Johnson then climbed into the back-bench row beside the woman, removed her handcuffs and began pawing at her, rubbing her shoulders and upper thigh, telling her he was attracted to her and had never been with a pregnant girl. He then repeatedly asked if he could use her belly as a pillow.

Laura repeatedly said no. Johnson swore at her and then climbed back into the front of the van.

When she was dropped off in Kentucky, Laura told a jailer what had happened.

She was instructed to write a statement which the jail sent to the transport company.

Federal investigators found that statement – recounting how Johnson inappropriately touched her – inside ISC headquarters when they served the search warrant.

KARE 11 obtained a copy of that statement along with the jail report about the incident through a public records request.

ISC’s owner Randy Cagle, when contacted by KARE 11, went on a profanity-laden phone call with a tirade of threats.

“When you were warned that he (Johnson) was misbehaving with women in your care, what did you do?” KARE’s A.J. Lagoe asked.

Cagle responded, “Go f*** yourself,” and hung up.

In court filings, Cagle has claimed all his employees received training regarding sexual assault, and quote, “I’m not sure how I’m responsible for common sense.”

At least 11 women report being sexually assaulted by Johnson after ISC was warned about his behavior, according to interviews and records reviewed by KARE 11.

Danielle Sivels of St. Paul is one of them.

“They need to be held responsible for what they did,” Danielle said. “Just because we’re inmates does not mean we’re not people.”

Johnson is far from being the first guard for Cagle’s company to be accused of sexual assault.

“They were sodomized, they were raped at gunpoint, they were deprived of basic human rights,” said Megan Curtis, another of Danielle’s attorneys accusing Ramsey County of failing to do due diligence before entrusting people in their custody to the private company.

“They have a responsibility, not only legally, morally to transport these women safely,” she added.

Chapter 5 A History of Rape

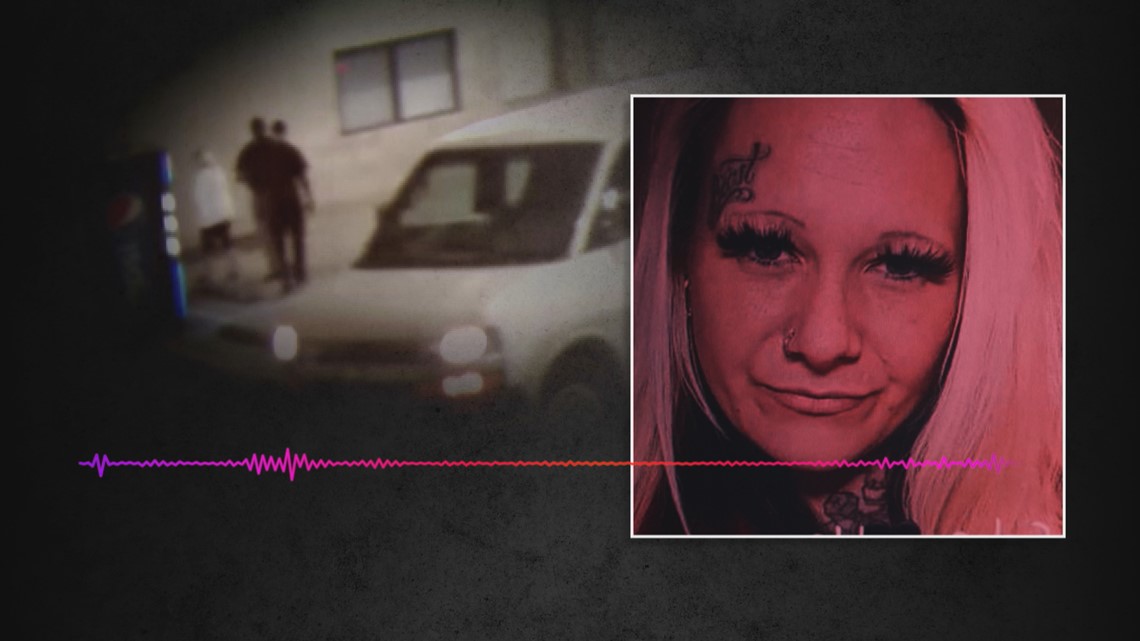

“I just want my story to be heard,” Jennifer Seelig said in a phone interview from Shakopee prison where she’s currently serving time.

Video from inside the sallyport at the Ramsey County Correctional Center in 2020 shows Jennifer being led into the jail by a rapist with a badge.

“Instills a lot of fear,” Jennifer said about wrestling with whether to report what had happened to her. She thought her rapist was an actual member of law enforcement. “Like, who’s going to believe me over that person?”

What she didn’t know, until informed by KARE 11, is Rogeric Hankins was not a deputy or police officer. He was just a driver and guard for a private company.

Jennifer was living in Olympia, Washington when she was arrested on a DWI warrant out of Ramsey County, MN.

Ramsey sent their private transport contractor ISC to pick her up.

ISC’s contract with Ramsey shows they were paid $1 per mile for out-of-state pickups of inmates and pretrial detainees.

Over the course of the nine years Ramsey contracted with ISC, an analysis of county procurement records reveals the company was paid more than $570,000.

In violation of the contract, once again, Jennifer says there was no female guard during her cross-country trip.

Late one night, the van pulled into a Missouri rest stop and Jennifer was escorted into the bathroom by Hankins.

“He actually raped me,” Jennifer said, “full-on raped me in the bathroom stall.”

When Hankins dropped her off at the jail in St Paul, he whispered to her to stay quiet.

“I’ll take care of you. Don’t talk about it, don’t say anything,” Jennifer says she was told.

When she saw a female guard at the jail she happened to know, Jennifer reported the assault.

Confronted by a Ramsey Detective in a recorded phone call, Hankins denied any inappropriate contact. “Hell no!” he responded, telling the investigator he was a happily married man.

A rape kit was done. The DNA proved Jennifer was telling the truth and Hankins lied about the sexual assault.

He was convicted and sentenced in July 2023 to nine years in federal prison.

Not all cases receive that level of justice.

ISC Captain Chris Weiss was accused in a 2017 lawsuit of violently raping an inmate in a rest stop bathroom.

Court records show the woman, named Crystal, also claimed Weiss forced her to perform other sex acts on him in the van and threatened if she reported it, “he would see that there were additional charges against her.”

Weiss’s partner, guard Ryan Moore, testified under oath in depositions that she woke up in the night and witnessed sexual contact between Captain Weiss and Crystal who was seated on the floor of the van between the two front seats.

Moore said it wasn’t the first time she had witnessed her partner sexually assault an inmate they were transporting. Weeks prior, she said she saw Captain Weiss acting inappropriately against another female inmate named Ashley.

“He stuck his hand down my pants while the van was driving,” Ashley said in an interview with KARE 11.

She says she was terrified because Weiss, who was transporting her from Colorado to Indiana for a probation violation on a prior drug charge, had complete control over every aspect of her life.

“So, it’s like you don’t want to make him mad,” she said, “but then I didn’t want that to happen either.”

Ashley, who says she’s now put her life back together and is set to graduate college in the Spring, calls it the worst moment of her life.

Despite that testimony from two victims and a fellow guard, the Justice Department brought no criminal charges.

Why not?

FBI Agent Vanhoose gave sworn testimony in the civil lawsuit brought by Crystal that he took the evidence he gathered to U.S. Attorneys in Arkansas, Arizona, and a lawyer at DOJ headquarters in D.C. “My case was closed because of jurisdiction issues,” he testified.

Because the victim and witness weren’t sure what state the van was in when the alleged sex assault happened, the U.S. Attorneys all declined prosecution.

“Which really makes no sense, that’s baffling,” said Abbate the former DOJ Civil Division Deputy Chief. “That should not happen! At all. That’s something that the Feds absolutely should have jurisdiction over, and it should not be an excuse to sexually abuse someone simply because they don’t know where the heck they are when it happened!”

ISC, while admitting no wrongdoing, settled lawsuits brought by both women accusing Captain Weiss of sexual assault.

He kept his job and was overseeing other guards for ISC who would go on to be accused of sexually assaulting women in their care.

KARE’s investigation has to date tied ISC and five of its guards to 21 sex assault allegations in the last 10 years where there’s already been a lawsuit, criminal charges or conviction.

“It’s horrifying but not surprising,” said Rita Lomio, a former Justice Department trial attorney who now works for the Prison Law Office. “And it shows a real need for additional investigation and action to protect people being transported between jails and prisons.”

“They have complete power and control,” Jennifer Seelig said of the transport guards. “Our entire lives are in their hands.”

While given that power and control over the people they haul around the nation in chains, private prisoner transport companies like ISC operate with virtually no oversight or regulation.

Chapter 6 Unlicensed

In Minnesota, the Board of Private Detective and Protective Agent Services is tasked with licensing companies providing private security.

Board President Rick Hodsdon, a lawyer and retired prosecutor, tells KARE 11 the licensing requirements include companies being paid to guard and transport inmates.

“So, if you are a company that transports prisoners,” Hodsdon said, “once you get to the state line, Minnesota’s regulatory requirements also apply.”

He added, private guards transporting prisoners without a state license is a gross misdemeanor.

KARE 11 enquired if Cagle’s company, ISC, has ever been licensed in Minnesota.

According to the State Board, there is no record of them being licensed now or previously.

Ramsey County has to date refused to respond to KARE 11’s questions about why they were giving tax dollars and entrusting the safety of inmates to an unlicensed company.

“They are feeding these women into exactly that situation where it’s a lamb to slaughter,” said Applebaum, the attorney suing the county.

Counties putting people into the custody of unlicensed contractors is not isolated to Ramsey County and ISC.

KARE’s investigation also discovered Hennepin County, which includes the city of Minneapolis, has contracts with the private company U.S. Corrections LLC to do prisoner transport.

U.S. Corrections LLC, whose company website states they “provide service to all 50 states,” is not and has never been licensed in Minnesota according to the state licensing board.

Hennepin County claims they were ignorant of the law.

A Sheriff’s Office spokesperson sent KARE 11 a statement which states in part;

“Hennepin County was not aware that entities engaged in the business of providing prisoner transport are required to be licensed by the State of Minnesota Board of Private Detective and Protective Agent Services. As soon as Hennepin County learned of this requirement and confirmed that US Corrections LLC is not licensed in Minnesota, the Sheriff’s Office immediately suspended using the vendor.”

U.S. Corrections President, Joel Brasfield, said in an email to KARE 11 that he disagreed with the position that his company needed to be licensed in Minnesota and it is “a no-brainer” that a license is not required.

Part of Minnesota’s licensing requirements include enhanced background checks and specific training for guards. Important requirements Minnesota’s licensing Board President explained, because the federal standards are incredibly ineffective.

“The federal standards are very weak,” Hodsdon said, “and they have a lot of gaps in them, and they don’t cover a large percentage of prisoner transports in the United States.”

Chapter 7 "None of it Happened"

The Interstate Transportation of Dangerous Criminals Act, also known as Jeanna’s Act, is the only federal law that provides guidelines or standards for the niche industry of private companies ferrying prisoners.

It was passed in 2000 in response to the killer of 11-year-old Jeanna North of Fargo, N.D. escaping from a private prisoner transport company.

The Act, which is supposed to be enforced by the Justice Department, is aimed at preventing prisoner escapes. However, it also sets basic training standards for guards and safety rules for the people being transported which if violated can result in $10,000 fines.

The Act requires, among other things, background checks for guards that include fingerprinting, a minimum of 100 hours of training, a female guard for female inmates and specialized training in the area of sexual harassment.

“None of it happened,” said Christina Hall, a former guard for ISC.

She told KARE 11 that when she started with the company, instead of 100 hours of training, she received 30 minutes focused only on how to shackle an inmate and spray them with pepper spray in the back of the van if they would not comply with orders.

She also said she was not background checked as the law requires.

“They just sent me to a place in Memphis to get my picture taken to make a badge, and I never had fingerprinting done,” said Hall.

While ISC owner Randy Cagle has refused to respond to questions, in court records from lawsuits filed against his company, he’s claimed “ISC performs a criminal background check and drug test on Agents before they are hired,” and, “After agents are hired and before they can begin transporting inmates, they are required to take 40 hours of classroom training offered by ISC.”

However, Leila Brown, another former guard with ISC said that’s not true. When asked how much training she received when she started at ISC with no prior law enforcement or corrections experience, she told KARE 11, “Probably about 35 minutes, 45 tops.”

Again, like Christina Hall, she said her training was only focused on how to work the shackles she would place on the detainees while transporting them for days and weeks at a time.

Brown also says her transport partner, Marius Nesby, who would go on to be convicted in Illinois after a female detainee accused him of sexual assault in a rest stop bathroom, bragged that he and a prior partner indulged in sexual favors from female inmates.

A Wisconsin woman also accused Nesby of sexually assaulting her.

Just as in the case of Captain Weiss, court records reveal the FBI investigated but brought no charges.

The FBI refuses to comment on why the WI case against Nesby was dropped, or even acknowledge they opened an investigation.

The WI woman won a $152,000 default judgment against Nesby and ISC, but her attorney tells KARE 11 they’ve yet to collect a dime from the company which is no longer operating out of their listed headquarters and is the subject of a growing number of lawsuits.

For the private transport companies, violating Jeanna’s Act carries little risk.

The law has been used just once, in 2013, to penalize a transport company that allowed a convicted sex offender to escape in North Dakota from an unlocked van.

In the 23 years the Act has been in existence, the Justice Department has failed to take any action to enforce the training and safety standards.

“Nobody is enforcing the standards that are out there,” said Abbate. “Nobody is looking at the regulations that are out there, there is no oversight of these companies! And when no one is looking, staff feel like they can act with impunity to commit crimes against the people they’re transporting. Nobody is looking and we need to.”

The federal law also has what legal experts describe as a major loophole. Jeanna’s Act specifically says the standards only apply to companies transporting “violent prisoners.”

There are no federal protections for non-violent people like Jennifer Seelig, extradited for DWI, or Dabrielle Dixon, accused of writing bad checks, or Danielle Sivels, transported from Dallas to St. Paul for probation violations.

“Sometimes inmate lives don’t matter,” said Danielle. “We just don’t matter. We’re just a number.”

Chapter 8 Broken Promises

Both Congress and the U.S. Department of Justice were put on notice years ago about inhumane conditions and deadly abuses taking place in private prisoner transport vans.

A blistering 2016 Marshall Project investigation laid bare a pattern of neglect, escapes, and deaths tied to the industry.

ISC and Randy Cagle Jr. were featured prominently, as the report detailed how a man with diabetes named Michael Dykes had to have both his legs amputated after spending three days in an ISC van while he said his requests for medical care were ignored.

The Marshall Project reporting was addressed in a House Judiciary Committee hearing.

Rep. Ted Deutch (D-FLA.) questioned then-U.S. Attorney General Loretta Lynch about the lack of federal oversight.

“General Lynch,” he said, “I’d just ask what can be done for us to focus on an issue that we were so concerned about here in Congress 16 years ago that we passed legislation, but that legislation seemingly goes unnoticed or certainly unenforced.”

He continued, “We’re not talking about pallets of laundry detergent we’re talking about human beings; we’re talking about American citizens. And no matter their crime, they deserve better than the way these transport services are treating them.”

Lynch responded that she would review the “extremely important issue” and report back.

Committee Chairman Bob Goodlatte (R-VA.) insisted that happen. “If the General would look into this in-depth and report back to the committee,” he said, “we would very much require that.”

KARE 11’s investigation finds, seven years later, there is no evidence the promised review and report to Congress ever happened.

No laws changed.

Rape and abuse continued unchecked.

“Nobody is looking, and we have to, we have to look,” said Abbate. “This is exactly what we need Congress to step up and do, to fix this problem, to protect the people who are in our custody that are abused by people who hold ultimate power over them.”

She added, “It’s time to act!”

Back in St. Paul, Danielle Sivels says she’s not hopeful meaningful reform will take place. For that to happen people would have to care.

“If it was your mother or your child or your sister you would care,” Danielle said. “And we are someone’s mother, we are someone’s child, we are someone’s sister.”

----

Special Contributions by KUSA Denver; John Charlton, WHAS Louisville; Drew Coffey, Eastern Illinois University; KING Seattle, WUSA Washington D.C., WFAA Dallas.