'They sweep, we move back': A homeless woman in Denver moved 5 times in 3 months

The policy to move people living on the streets has spread out camps from a central core into neighborhoods unaccustomed to the tents and the people living in them.

Carrie Gladue, 44, is a mother of three. Born and raised in Denver, she spent much of 2021 sleeping in a tent and walking to and from Denver Health’s methadone clinic.

She struggles with the summer heat and winter chill and said she detests people who hurl trash and insults her way. When offered housing help, she declines.

“I don’t want to be put under a microscope,” she said. Next year will be her fifth year living on the streets.

Gladue has never met the city’s mayor and, to be honest, wouldn’t really know what to say to him if she did run into him.

But few people have had more power over her life than Mayor Michael Hancock. His policy of forced removal from what he calls unsanctioned encampments has forced Gladue into even more of a vagabond lifestyle.

In the three months we followed Gladue, she moved five times.

She might not consider herself a symbol of the city’s ongoing and oftentimes futile efforts to rid itself of impromptu camps. But if the city and its mayor are going to have sustained success with those efforts, they have to persuade people like Gladue to take a chance on city services.

As of now, she said she's not ready to give in.

“We get about three weeks out of every place, most of the time,” she said. “That’s how we play the game.”

It’s a game being played inside an ever-expanding arena, a 9Wants to Know investigation found.

Chapter 1 The Game

City officials call them cleanups. Those who are the subject of those cleanups routinely call them sweeps.

Whatever you call them, few city policies have had more impact on the day-to-day lives of the unhoused on the streets than the frequent and forced removal of the encampments in which many of them live.

According to records reviewed by 9Wants to Know (9WTK), the city’s efforts have increased not just in frequency but in scope.

In 2020, the city removed 50 encampments.

Through Oct. 28, 2021, the city removed 83 encampments this year.

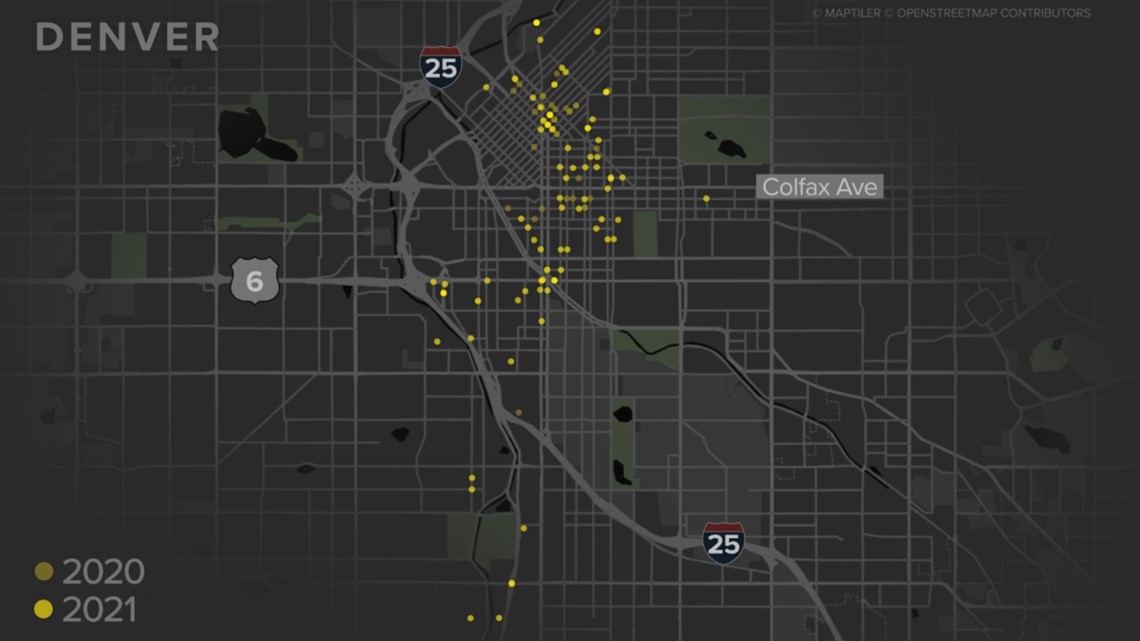

In addition, the 9WTK investigation found the city’s forced removals appear to have spread encampments out from a core area just east of downtown.

Once confined to a general area around 24th and California streets, it’s now routine for city crews to clean (or sweep) camps miles from that area.

Gladue said it feels like a game -- one that forces her into neighborhoods that she knows she’s not welcome in.

“Lots of houses, lots of people, lots of angry people who don’t like us,” she said.

She said she prefers more industrial areas. When we first met her, she was living in a camp near West 6th Avenue and Quivas Street. That area has been cleaned, or swept, five times this year.

“They sweep, we move back. They sweep, we move back,” she said.

Her 20-year drug addiction hasn't waned through the moves. Methadone keeps her away, for the most part, from heroin. Meth remains a daily part of her life, she said.

“It’s just a part of who I am at this point,” she said.

Death, or at least the specter of it, looms large over her life. She figured she has known “dozens” of people who have died from overdoses during her time on Denver’s streets.

“I worry about that a lot," she said. "I worry about that often. I don’t want to die out here."

That worry has yet to persuade her to do something about it.

“I want this to be harder for me. I don’t want to get used to this," she said. "I don’t want to get used to this, but it seems the longer I'm out here, the more used to it I’m getting."

Chapter 2 Mayor: 'It's just not safe'

“We’ve got to find a way to connect [her] closer to services and to help her become more stabilized and self-sufficient,” Hancock said when asked about Gladue's story.

The Denver mayor was quick to point out the millions of dollars the city has spent and will continue to spend to help people like Gladue, but he admitted his office has more work to do.

“Until [Gladue] trusts these services, we’re going to continue to stay on her and do what we can to connect her,” he said.

Just don’t look for him to discontinue what he still calls cleanups.

“We’ve got to do what we can to help them, but we cannot allow these encampments to exist. It’s just not healthy. It’s just not safe,” he said. “The alternative of having them there as opposed to cleaning them up and trying to connect them to services is just untenable. It’s unacceptable.”

His opponents on the issue remain frustrated, to say the least.

“It’s really unfortunate that we have a mayor who is so close-minded to solutions,” said Ana Cornelius with Denver Homeless Out Loud.

Denver Homeless Out Loud did a study in 2020 that largely mirrored some of the things we found during our investigation.

For example, the study found 70% of those removed from encampments returned to the same site within weeks of the removal.

One location, 29th Street and Arkins Court, has been swept (or cleaned) six times since the start of last year.

“People do go back to some of the same spots,” Cornelius said.

If they don’t, she said, they’re moving farther and farther from resources they need.

“They may have a resource that is close," she said. "They may be close to a service provider that they frequent."

When Gladue moved to an encampment near South Elati Street and West Cedar Avenue in the late summer, it would take her sometimes as much as an hour to bike herself and her two dogs to Denver Health’s methadone clinic.

One hour, one way. Another hour back.

“I haven’t slept in about three days,” she said.

Chapter 3 Fences go up, people move out

Thanks to a court order, Denver now gives residents of the encampments seven days to get out before crews come in and remove everything from the site.

We met Rick right before the city moved into a camp at Elati and Cedar. Rick didn’t want to give us his last name.

“I’ve been here about two weeks,” he said. “Sometimes we get to stay a month. Sometimes it’s two weeks, and we just have to find another place to go to. It gets old."

The day of a sweep/cleanup, Rick is up at 4 a.m. That’s when city crews and city contractors move in with the fences.

Fences go up, and people move out.

Once a common object of local news crew scrutiny, these days you’ll seldom see a camera around.

You will, however, frequently see a woman named Amy Beck.

We found Beck working a sweep/cleanup near 6th and Quivas.

“It’s been swept pretty regularly since February,” she said.

Beck is paid by no one to be here. She simply volunteers to help make sure people are appraised of their rights. “If we want to see these people thrive, we have to offer more housing,” she said.

“When they are swept, their lives are disrupted for days, if not weeks,” she added.

Gladue described the process this way: “They come in at 4:30 in the morning, and they fence the whole thing off. They sit on top of people, and they then come around 6:30 and they say, ‘You have until 8:30 to get out of here.’ We’ve heard it all before. And, so, we go, ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah.' ”

“There’s got to be a better solution," she said. "I can’t for the life of me think about what that solution could be, but something.”

Gladue acknowledged that almost everywhere she might decide to go next will result in someone being upset. “We don’t want to be in someone’s front yard. We don’t want to be near businesses,” she said.

What would she tell Hancock her solution is?

“I don’t know. I don’t know what to do,” she said.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Investigations from 9Wants to Know