DENVER — On June 3, 2022, multiple lives were turned upside down and changed forever. That's the day Denver Police (DPD) responded to an apartment in the 1900 block of Ulster Street for a call about a child who was unresponsive.

The boy, 8-year-old Dametrious Wilson, died from his injuries. He and his older sister, Noelle White, had been in the care of their great-aunt, Susan Baffour, who was arrested and charged with murder in the case. She's pleaded not guilty and is set for trial this summer.

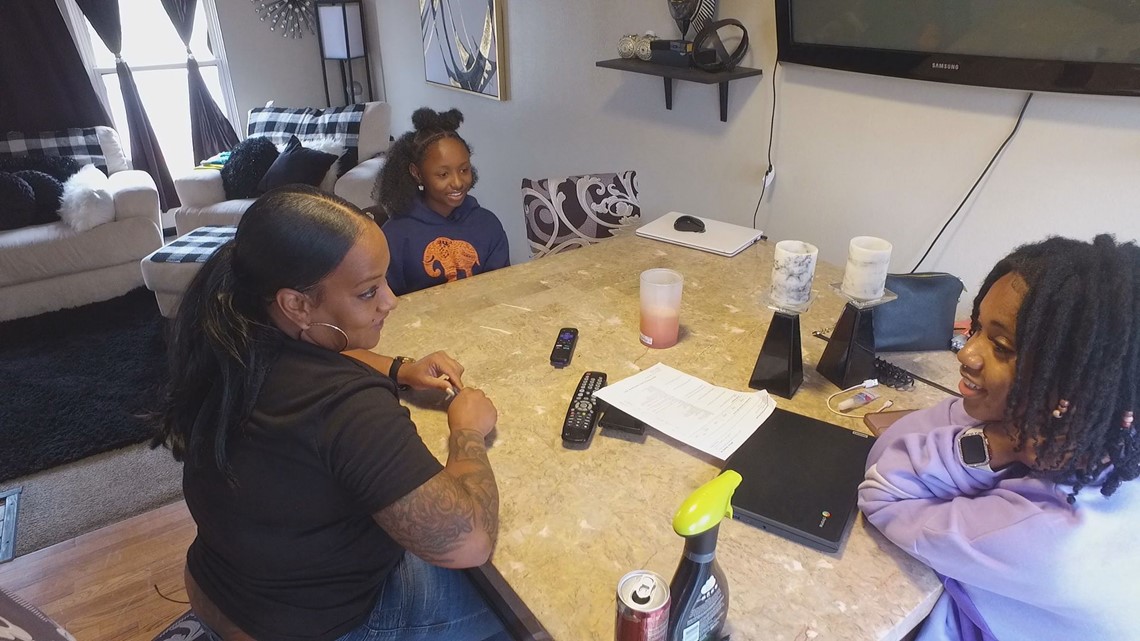

“We walked this together. She's been so pleasant, so happy, so strong through all of this. But it was a whole process,” Candance White said about her niece, 11-year-old Noelle.

Since her brother's death, she's been searching for stability and found it at her aunt's home.

"It was just the case worker came, dropped her off some stuff, and was pretty much like we'll talk soon,” White said, recalling the day Dametrious died and Noelle was welcomed into her home.

"I was scared. I was scared. Because not only am I taking in another child, I'm taking in a lot of responsibility with that child,” she added.

Noelle was at the home on the day her younger brother was found dead. According to an arrest affidavit from Denver Police, he was beaten with a wooden back scrubber by Baffour, who was chosen and trusted by the family and Denver Human Services to care for the two siblings in 2017.

For the past year, White's been learning how to navigate Denver's often complicated child welfare system. She learned the responsibility of kinship care came with two options.

"It was like you can be certified or uncertified. My first thought is I'll be uncertified. It's my niece," she said, though the differences between being uncertified vs. certified were not clearly laid out to her.

Becoming certified enables kinship caregivers to receive money from the state — anywhere between $1,200 and $1,500 a month.

"In order for me to ensure I could provide for her like I provide for my children, I went certified," White said. "I don't really to this day understand what the huge difference is. Besides them sending me a check. I don't know.”

Certification comes with a lot of hoops and hurdles that include training and inspections, similar to the foster parent process.

"I've never dealt with Human Services before, I've never dealt with people inundating my life, and that's all it has been. It's just been a lot to have her,” White said.

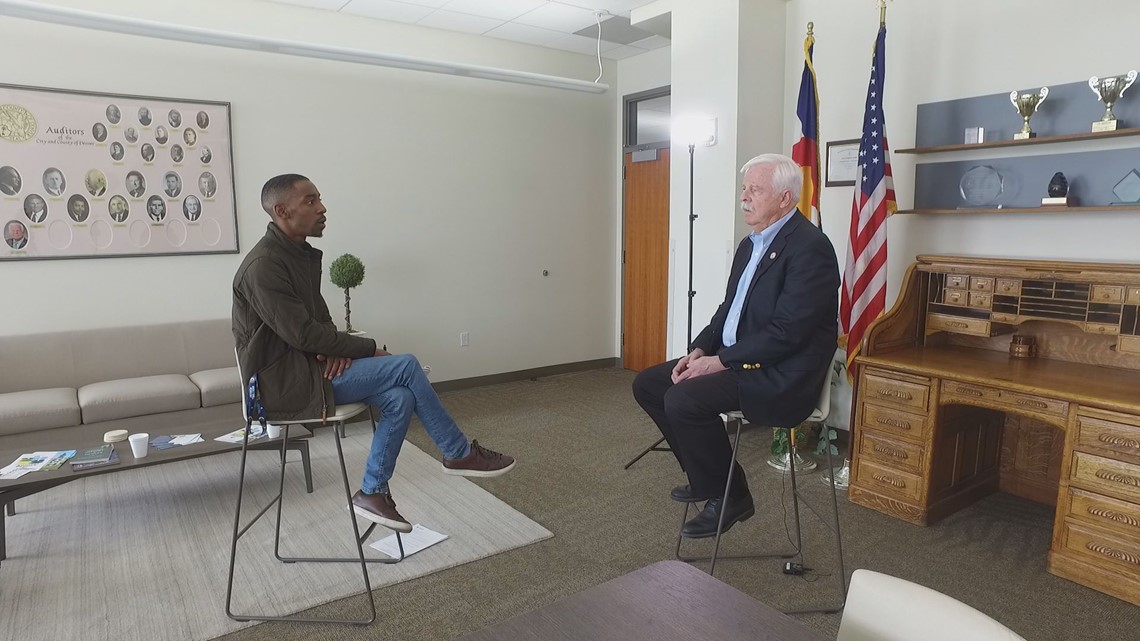

Denver Auditor Tim O’Brien said children like Noelle are part of an “at-risk” population they’re concerned about. He also believes that the certified caregiver payment is essential to the care of these children.

His office conducted an audit in March 2023 that questions how effective the kinship certification process is within Denver Human Services.

"The training given to the people who would certify somebody to be a certified caregiver is inconsistent, and that means the quality differs from person to person,” O’Brien said.

According to the report, as of September 2022, 1,600 children in Denver were placed within kinship care, meaning they're with relatives or other people with a significant relationship to them. Only 263 of those caregivers are certified.

"If you are not certified, you don't get those resources," O'Brien said. "If you don't get those resources, that impacts the kind of care you are potentially able to provide for a child.”

While non-certified caregivers might not get the those payments of approximately $1,200, they are eligible for other resources, according to DHS. The agency said it has 24 dedicated staff members who can provide support and connection to benefits such as parenting support, and financial support for items such as diapers, car seats and beds.

“We acknowledge and are sympathetic to the challenges kinship caregivers experience and strive to equip them with the resources they need to maintain the health, safety, and best interests of any child in their care," Denver Human Services said in a statement in response to the audit. “Our goal is to connect parents and families with our resource engagement and prevention services, like our Denver Parent Advocates Lending Support (DPALS) program, before kinship care or other interventions take place.”

How does an agency with oversight over so many children and families not have certain policies and procedures in place or some policies that are still in draft form?

"They also have a fairly high amount of turnover," O'Brien said. "People that are moving on to another job in the department or just getting out of Human Services altogether."

After the audit, O’Brien’s office laid out several recommendations that are meant to be implemented by the end of this month.

"What we recommended is that they have a program that has structure to it. That they can measure the outcomes of the training program that they provide to the individuals working in the department," O'Brien said.

"All of that goes with the training program," O'Brien said. "A curriculum, feedback, making sure that you're consistent in the quality of the education that they're providing so those people can educate the caregivers.”

Victoria Aguilar, a spokeswoman for DHS, told 9NEWS that all the recommendations have already been put in place or would be in place by the deadline of May 31, 2023.

The hope is that the recommendations will mean that caregivers like White aren't left trying to figure out the child welfare system on their own.

"Through this whole process, nobody really told me what this entailed. It was kind of like on the surface. But when you don't know, you don't know," White said. "I just want Human Services to have a sit down with all the agencies they involve and come together."

Part of her frustration is how much Noelle is being constantly checked on while they’re trying to heal from the trauma of their loss, though no one checked up on Dametrious and Noelle when they were in the care of Baffour.

"Where was, 'what does she need, are you safe' then?" White questioned. "Now you're over here, you've taken everything from me short of blood. Once a month. Sometimes every three weeks you're over here. Asking me the same 10 questions."

When Baffour was granted allocation of parental rights in 2017, no additional followup was required by DHS under current state law. After their placement, DHS was contacted twice about concerns related to at least one of the children, according to records obtained by 9NEWS. Both complaints were screened out for not meeting the criteria of abuse or neglect.

She said she wonders whether Dametrious would be alive if more questions were asked of Baffour while the siblings were in her care.

"It’s hard. It’s hard knowing her [Noelle's] brother is not here. It’s hard visiting a cemetery. I've lived his life three times over," she said. "It’s hard wondering what he would be like, how they would be together. You know. And I just feel like this process is failing so many families.”

There have been highs and lows, White said, but in the end, "The outcomes are high. Cause I have Noelle. That through everything, that's the best part.”

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Finding the Gaps: The Death of Dametrious Wilson