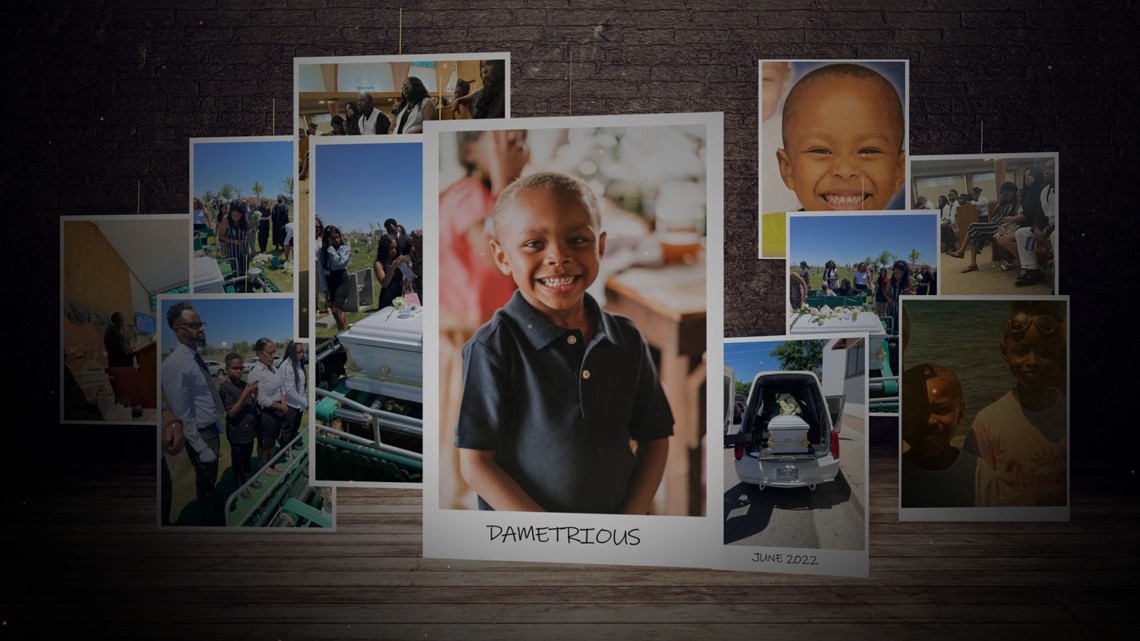

DENVER — An 8-year-old boy who was beaten to death in June missed 60 days of school in the year before he died, according to attendance records reviewed by 9NEWS.

On June 3, Denver Police responded to an apartment for a call about a child who was unresponsive. That child 8-year-old Dametrious Wilson died from his injuries, and since his death, 9NEWS has been looking into the circumstances.

That morning, Susan Baffour, Dametrious' great-aunt called 911 to report that the boy was not breathing. Police responded to their apartment in the 1900 block of Ulster Street around 8:20 a.m.

Baffour told police she spanked Dametrious the night before, an arrest affidavit from Denver Police says. She's since been arrested and faces charges of first-degree murder and child abuse in connection to his death.

She appeared in court on Dec. 9 for an arrangement hearing, but it was delayed until February due to her attorneys leaving the public defender's office. Baffour's new counsel said they needed time to get up to speed on the case.

For months 9NEWS has been working to learn if something could have been done to prevent the death of this little boy. School records show there were signs of potential issues.

When children can't speak for themselves, others need to speak for them. Those people with a voice are called mandatory reporters and are mandated by law to speak up.

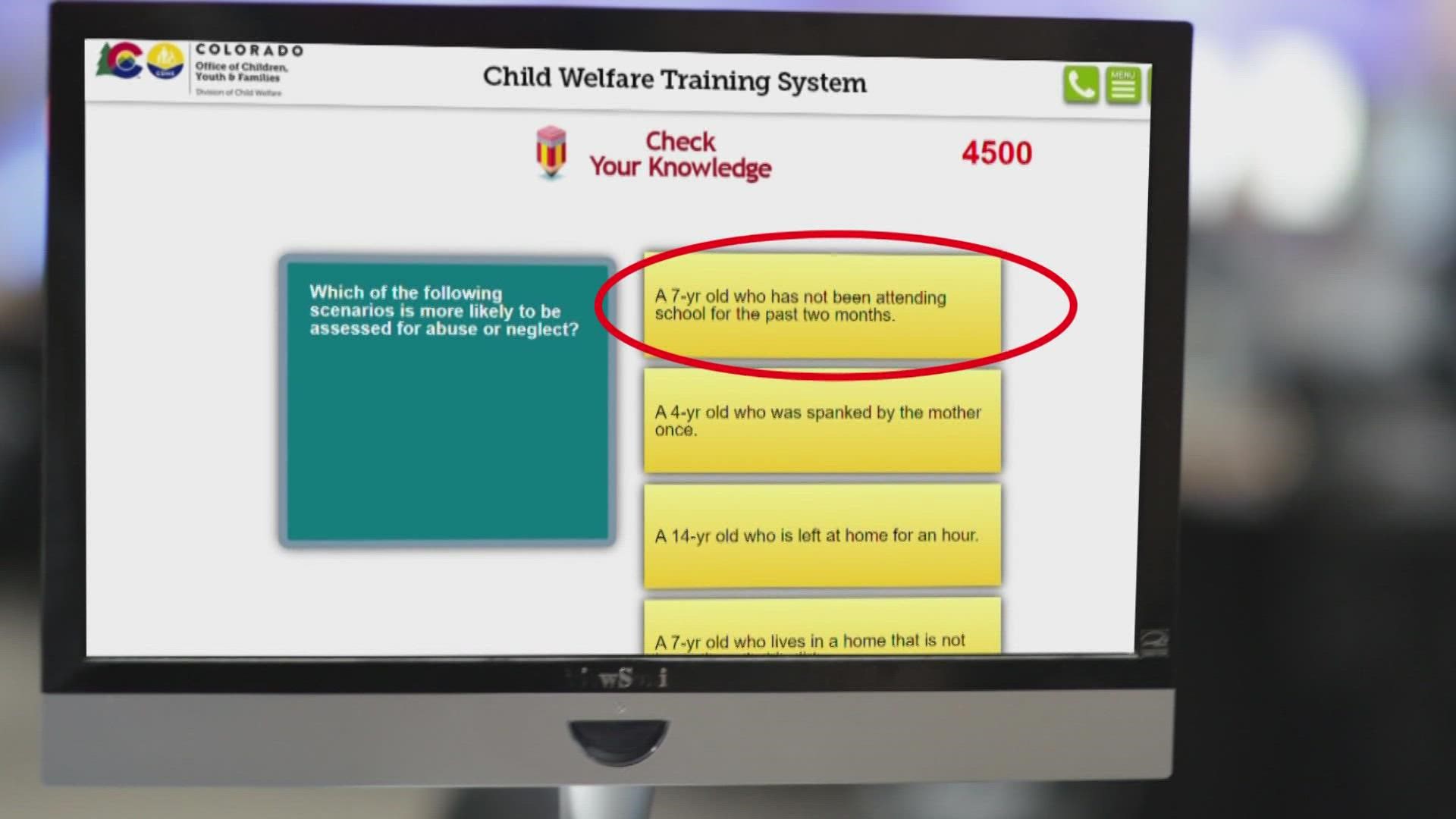

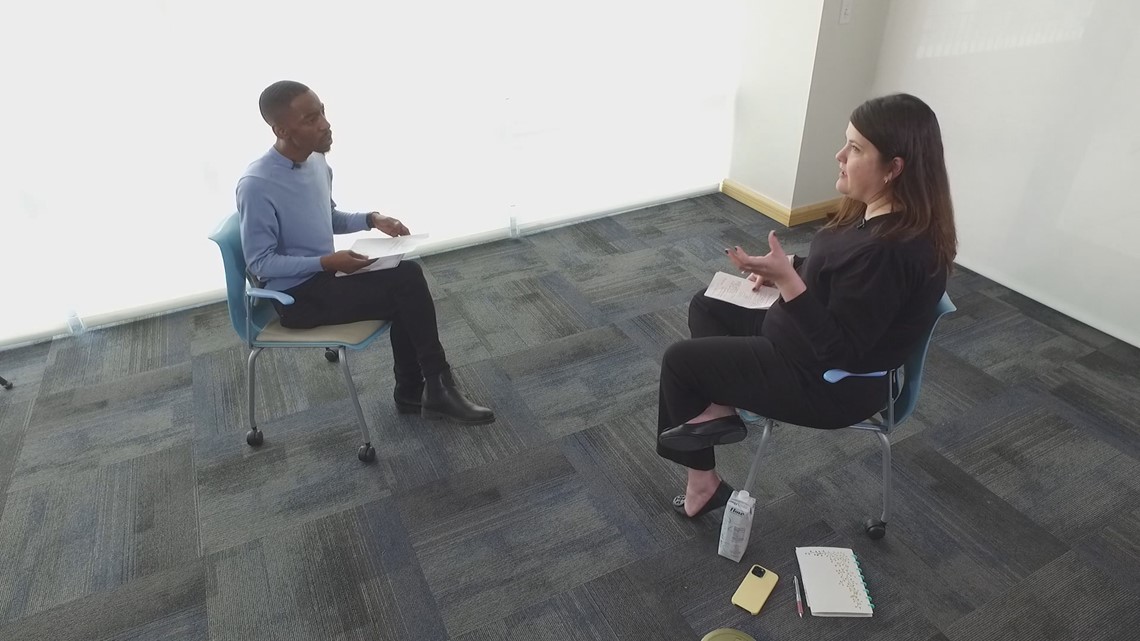

"These professionals are a really key part of our child welfare system…They get to know and build trust with children who as trusted professionals children confide in, children talk to,” said Ida Drury. She's with the Kempe Center and is the principal investigator of the Colorado Child Welfare Training System.

Drury works at the Kempe Center at The University of Colorado in Aurora. The center works with the Colorado Department of Human Services to train 15,000 mandatory reporters every year. That includes teachers who see it all.

"Neglect constitutes about 80% of the reports they see in Colorado,” Drury said.

Educational neglect is when a student misses at least five days of school per month. That's when teachers are trained to make a report to Human Services.

"I think educational neglect is hard. Even in the child welfare system whether or not it rises to the level of abuse or neglect is a much higher bar,” Drury said.

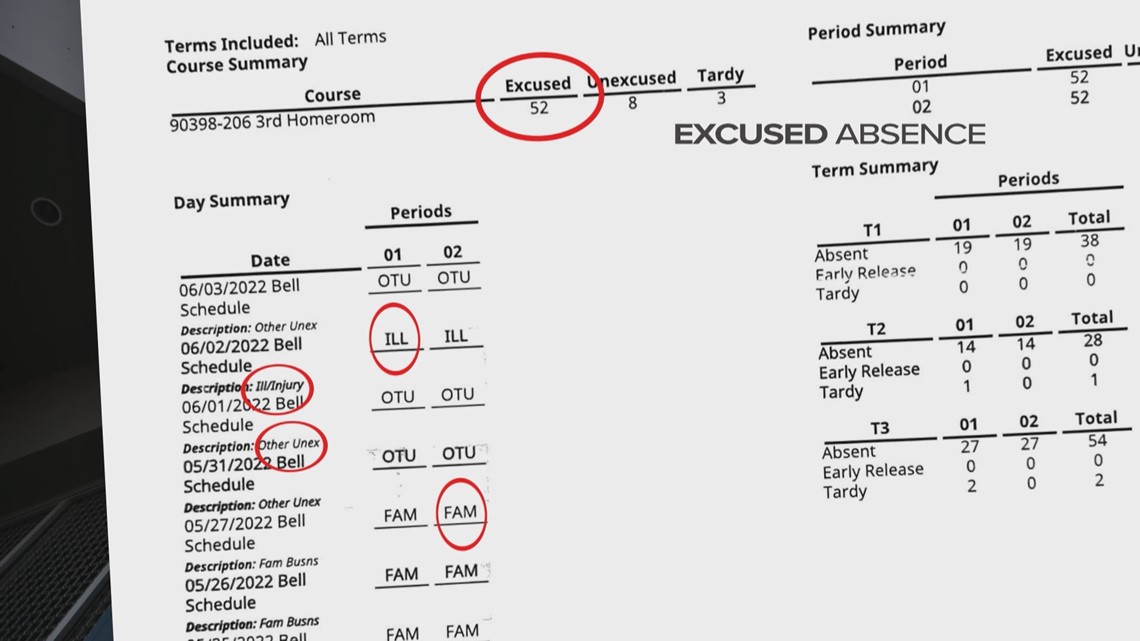

Dametrious missed 60 days of school at Ashley Elementary during the 2021-2022 school year prior to his death.

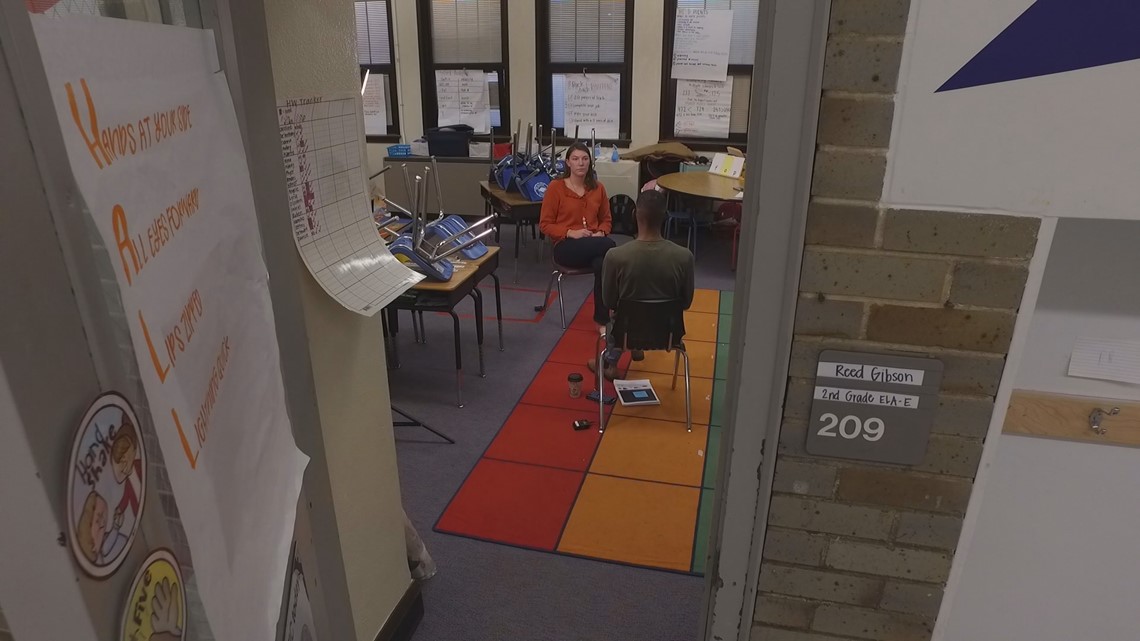

"He did miss usually at least one day a week,” said Dametrious’ second grade teacher, Reed Gibson.

Based on attendance records from Ashley Elementary, Dametrious was a victim of educational neglect during the school year leading up to his death in June 2022. Just 19 days into the school year he had already missed 10.

“Susan had emailed asking if we could put him on remote learning and we told her that that wasn't an option,” Gibson said.

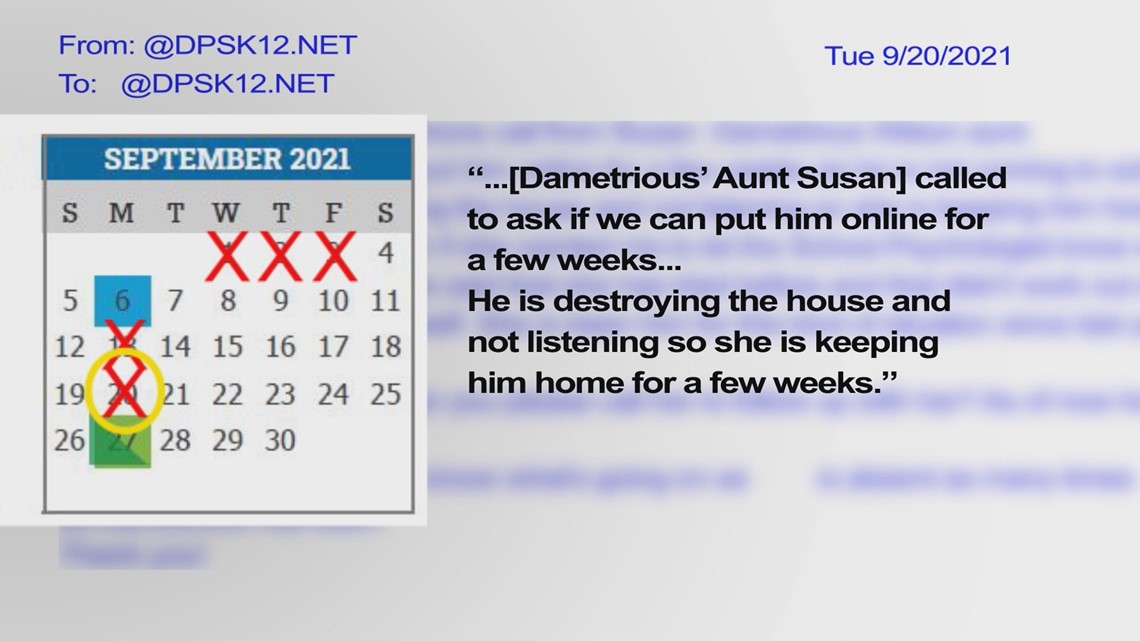

On Sept. 20, 2021, Dametrious Gibson got an email from the school attendance secretary in the office.

"It wasn't right that she [Susan] was trying to keep him home for two weeks,” Gibson said.

"Dametrious' Aunt Susan called asking to put him online for a few weeks. He is destroying the house and not listening. So, she is going to keep him home for a few weeks,” the secretary wrote in part.

No call was made to Human Services.

"Can I just be straight up with you; I don't think that would've gotten screened in. I mean if you called just that in, I don't see the suspicion there necessarily,” Drury said.

Instead, Denver Public Schools tried to handle the absence internally by sending the department of public safety to conduct a welfare check. No one answered the door and there was no request for follow-up.

"We've heard of this a lot, I think institutions try to manage their personnel in their own system... does that make sense to have extra stop gaps to make the report,” Drury said.

Throughout the rest of the school year, Dametrious missed a minimum of five days per month for five consecutive months. His absences went unreported to Human Services.

"Ultimately if you're calling the hotline and you're making a report of child abuse or neglect over that hotline that meets your muster for making a report of child maltreatment. It’s as simple as that,” Drury said.

Two previous reports made about Dametrious and his older sister Noelle were screened out meaning they were not investigated any further. One was in November 2019, and a second was in October 2020.

"Screen out fatigue is something that I heard from mandatory reporters that is so discouraging,” Drury said.

The difference is these processes are some reasons why the clarity surrounding the law raises questions for many who care about the well-being of children.

"Mandatory reporting laws are flawed for a number of reasons,” said Colorado’s Child Protection Ombudsman Stephanie Villafuerte.

She says it's flawed because some mandatory reporters don't understand how the law operates which can result in a lack of reports.

"There's a lot of ambiguity around the law. We have, I think, amended Colorado’s law 31 different times. But not in a substantive way, we keep adding more reporters…and really, it's because of the lack of precision in which we write these laws in which we train professionals. We're leaving kids exposed on all ends,” Villafuerte said.

Drury and Villafuerte agree Colorado has been too general as a child welfare system. Now a task force has been created in hopes of improving the training and the law around reporting.

“All are invested in this idea that we can come together and create a system where we are more accurately identifying those children who may be at risk,” Drury said.

The mandatory reporters on the task force want to simplify the process and improve the voice for children who need it most.

"We want to make sure as mandatory reporters they're doing a good job and reporting the types of things they don't look back on later and say oh shoot I knew something was happening there and I just didn't get the chance,” Drury said.

The task force has 13 meetings over the next two years. The goal at the end is to develop a plan and present recommendations for a potential change in policy and training. Essentially, they want to completely transform the system.

The mandatory reporter training is available online in both English and Spanish. You do not have to be a mandatory reporter to take the training, but it does create more eyes and ears for children who may be experiencing abuse or neglect.

If you have any information about this story or another story idea, email Darius Johnson or Janet Oravetz or Anna Hewson.

If you suspect a child is being abused or neglected call the Child Abuse and Neglect Hotline at 844-CO-4Kids. The hotline is available 24 hours a day, every day.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Finding the gaps the death of Dametrious Wilson