John DeHerrera was on-call for work the first day of 2002. But when the phone rang, it wasn't his supervisor – it was his brother calling to tell him their sister was dead.

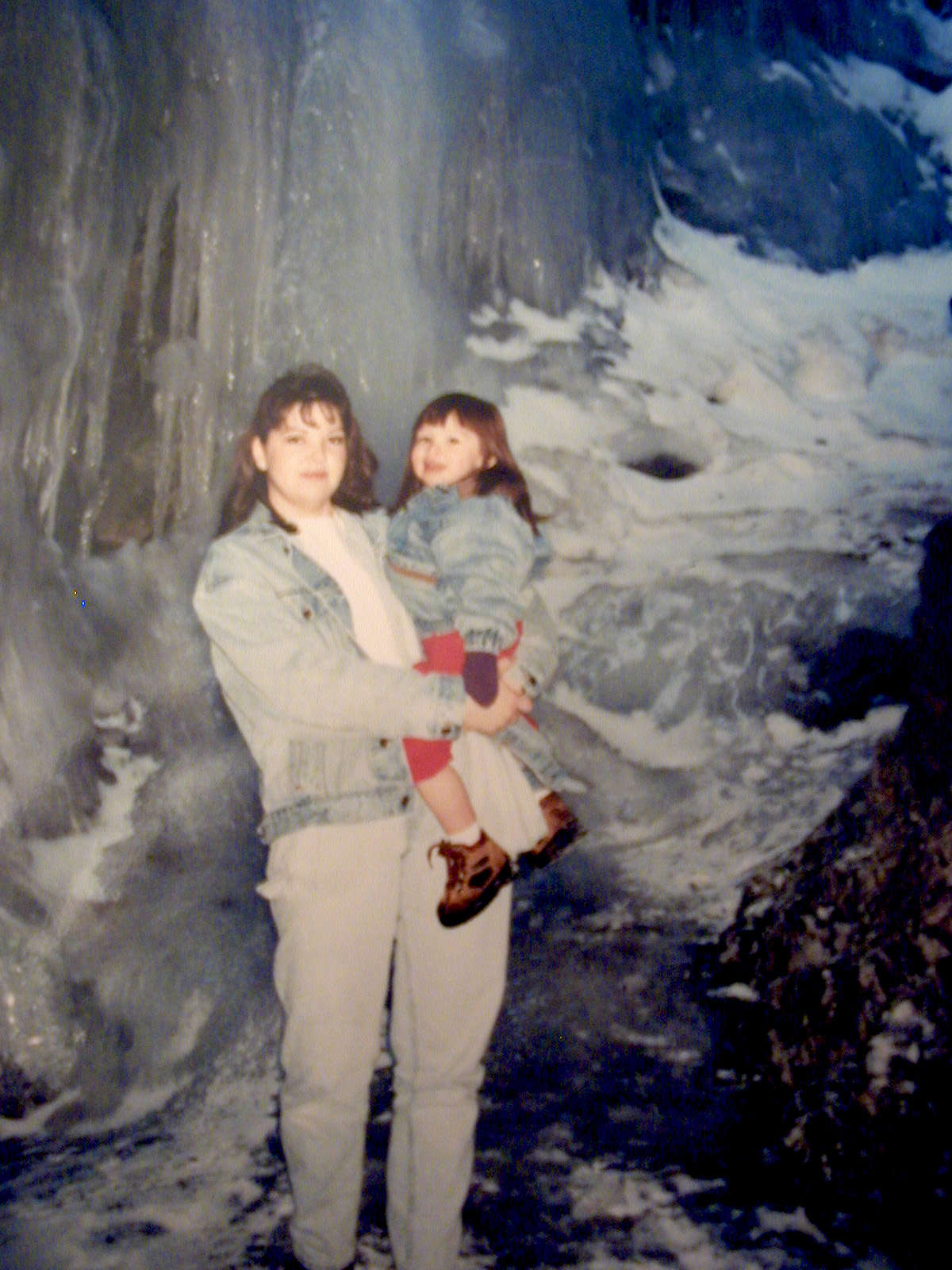

Deborah Garcia was 34, a mother of two small children and seemingly in good health. But on Jan. 1, 2002, she was rushed to the hospital in Alamosa after her husband told authorities he found her in their bed, unresponsive.

Because Alamosa County's coroner was not a forensic pathologist – the kind of specialized doctor qualified to perform an autopsy – the investigation of Deb Garcia's death was turned over to Dr. David Bowerman in El Paso County.

He concluded that she suffered a sudden cardiac death as a result of three undiagnosed heart conditions, according to a copy of her autopsy report obtained by 9NEWS.

“He assured us that he did a very thorough autopsy and, you know, that he had found something wrong with her heart,” DeHerrera, who lives in Aurora, told 9Wants to Know. “We had no course to say anything other than go by what his authority was and go on from there. That's what we carried on with our lives with.”

Then, after a discussion in August 2014 about exactly what heart conditions afflicted Deb Garcia, her sister sought another opinion. She sent her autopsy report and photographs to another forensic pathologist, who ultimately also examined the microscopic tissues taken from Deb Garcia's heart during her autopsy.

His conclusion, according to a lawsuit filed by members of her family last year: Deb Garcia's heart was normal and her death was a result of suffocation.

The family's lawsuit names her husband as her killer – something his attorney said he categorically denies – and seeks the return of life insurance proceeds, cash and property he inherited after her death.

And her case joins others as an example of why some people think Colorado's civilian coroner system – which dates to the Old West and has few requirements for the men and women who hold the important job of determining how and why people die – should be reformed.

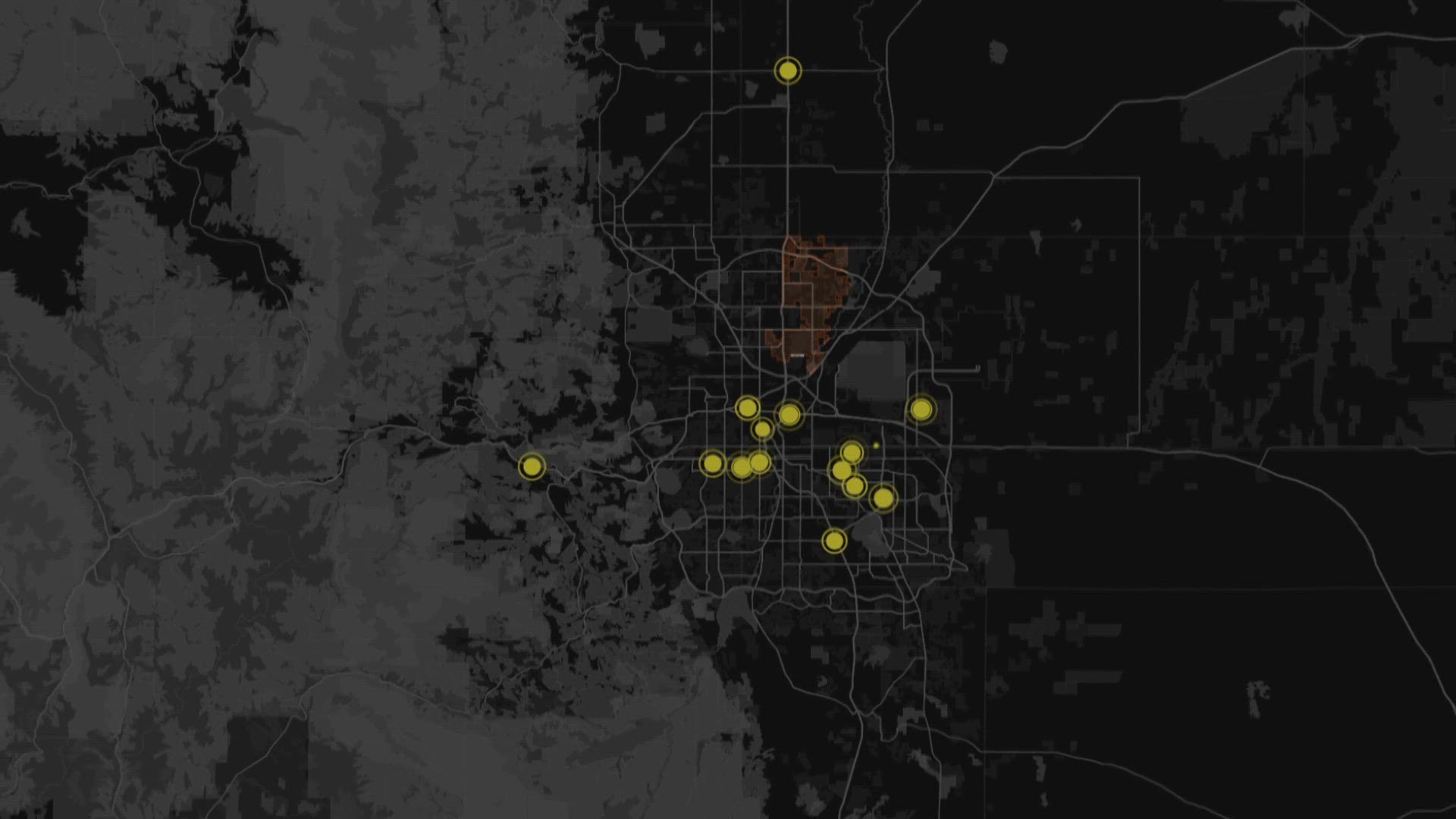

A yearlong 9Wants to Know investigation found that system is a patchwork of haves and have-nots where money sometimes determines whether an autopsy is performed and where some counties have deputy coroners on the job who aren't trained in death investigation.

It's a system where funding and caseloads vary widely between urban and rural counties.

And it's a system that costs on the order of nearly $22 million a year, 9Wants to Know determined after surveying coroners across the state and examining hundreds of pages of public records.

According to court records and other documents obtained by 9Wants to Know, Deb's husband, Joe Garcia, told investigators that when he'd gotten up on New Year's Day 2002 she'd seemed fine but stayed in bed. Later that day, he checked on her, found her unresponsive and called 911.

The lawsuit accuses him committing “the crime of murder in the first or second degree, or manslaughter, by feloniously killing his wife by asphyxiation ...”

Erich Schwiesow, an Alamosa attorney who represents Joe Garcia, told 9NEWS he flatly disputed the allegation. Joe Garcia, he said, denies having anything to do with his wife's death.

Schwiesow said he believes the lawsuit is “going nowhere.”

“It was a mysterious death that was investigated as a homicide with the focus being on her husband, Joe Garcia,” said Baine Kerr, a Boulder attorney who represents Deb Garcia's family.

That investigation was dropped five weeks later after the autopsy report came back. Bowerman concluded she'd died suddenly of undiagnosed heart problems – a “natural” death.

Kerr argued that not only did Bowerman make a mistake, but that it is emblematic of the problem with Colorado's coroner system. To be a coroner, one merely needs to be 18, a U.S. citizen, a resident of the county he or she will serve and cannot have a felony conviction.

The reality in Colorado today, according to 9Wants to Know's surveys of coroners across the state, is that only a handful are forensic pathologists, and those who are can make money on the side performing autopsies for other counties.

That's exactly what happened in Deb Garcia's death, Kerr said. Bowerman performed 210 so-called “private” autopsies in 2002, making money on each one of them – he was personally paid $700 for Deb Garcia's – in addition to the salary he earned as El Paso County's coroner, Kerr said. In that capacity, he performed another 345 autopsies, detailed forensic examinations and dissections that can take two to four hours to complete.

That's 555 autopsies in one year; more than twice what the National Association of Medical Examiners recommends as an appropriate caseload for a forensic pathologist.

“To whom is the pathologist beholden, or the coroner beholden?” Kerr asked. “He's an elected official with a public salary who is charged with investigating deaths in El Paso County. And it's a system designed to ensure his independence. He does not answer to the DA, to law enforcement, to defense lawyers, to the hospital establishment, to the medical establishment. He answers to the citizens of El Paso County.

“However, in these private autopsies under contract with rural counties for profit, he answers to the people he contracts with, and in this case that is completely managed by law enforcement.”

Kerr said it's an obvious conflict of interest.

Colorado is one of 14 states that still relies on a civilian coroner system, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Sixteen other states – including Utah and New Mexico – have gone to centralized medical examiner systems, where doctors, not civilians, are in charge.

The push to abandon the civilian coroner system is not new. Massachusetts went to a medical examiner system in 1877. National experts recommended that model be adopted across the country in 1928.

Many Colorado coroners defend the current system.

“I think you'll find that a lot of people have a lot more than just the minimum requirements,” Emma Hall, Boulder's coroner for the past 6 ½ years, told 9NEWS. “I have a lot of people that will joke with me. They'll hear, 'Oh that's all it takes to be coroner, I'm going to run for coroner.' And they don't have the faintest idea about anything to do with death investigations.”

She and others point with pride at a relatively new requirement: every coroner become a certified death investigator within a year.

But 9Wants to Know found at least a dozen counties where deputy coroners, who often have to step in and handle cases, aren't certified.

“It's a big loophole,” said Dr. Michael Dobersen, who served more than 20 years as coroner in Arapahoe County before retiring. “If the coroner happens to be out of town, obviously the deputy coroner is in charge. And without the proper training, certification, we're right back where we started from.”

Hall and other coroners are closing that loophole on their own. She is among the Colorado coroners who require their deputies to become trained as death investigators within a year.

“It's a big deal to us that makes sure that our staff are qualified and experienced and trained,” she said.

Other smaller counties struggle with it. Becoming a certified death investigator means attending multiple autopsies and going to multiple death scenes. In some of Colorado's rural counties, the caseload is so small – there were seven cases in Cheyenne County last year – that meeting the requirements for certification can take years.

Darren Dake, a deputy coroner and investigator in Crawford County, Mo., and a consultant in death investigations, questioned whether that is good enough.

“If your daughter was in another county and met her demise in some way and the person that showed up on that scene was the deputy coroner that wasn't registered with the state, had no formal training, and nobody even knew his name, would that be the appropriate person to investigate your daughter's death?,” he asked.

And 9Wants to Know also found vast discrepancies in resources in various counties. The budget in some of the state's largest counties is in the millions, and in some of the smallest ones it's no more than $20,000. Some Colorado coroners make less than $10,000 a year, meaning they need another job to survive.

That disparity in resources can affect decisions made during investigations.

Fremont County Coroner Randy Keller was one of the coroners who acknowledged that he has to think about his budget when deciding whether to order an autopsy.

“We run into some issues with funding that we only can do so many autopsies a year, so we've got to be a little discretionary,” he said.

Fundamentally changing Colorado's system would require new legislation. That doesn't look likely at the moment. Past efforts have all failed, and there is nothing on the horizon in the way of new legislation.

One thing that's not in dispute: John DeHerrera feels let down by the people who were supposed to give his sister a voice.

“For this this homicide to have happened that long ago and it slipped through the coroner's fingers and the investigator's fingers with the Sheriff's department, and everything that's transpired … it's challenging to deal with it,” he said.