From checking up on ex-mistresses to getting dirt on a girlfriend’s boss to trying to get a date, 9Wants to Know found Colorado police often avoid criminal charges when they illegally access law enforcement databases for personal reasons.

After an extensive review of discipline records, court documents and other public information, 9Wants to Know found far more misconduct cases compared to cases resulting in prosecution.

The databases protected by law

The National Crime Information Center (NCIC) and Colorado Criminal Information Center (CCIC) are important federal and state databases police use during criminal investigations. They contain loads of private information on citizens like private phone numbers, addresses and property information.

Using NCIC and CCIC without valid reason is considered a crime under respective federal and state laws, however officers who are caught abusing the systems are rarely charged.

“We haven’t found that there’s been enough stringent discipline, at least on the abuses that we know about,” said Denise Maes of the Colorado ACLU. “It is not a toy and it can’t be abused.”

The numbers

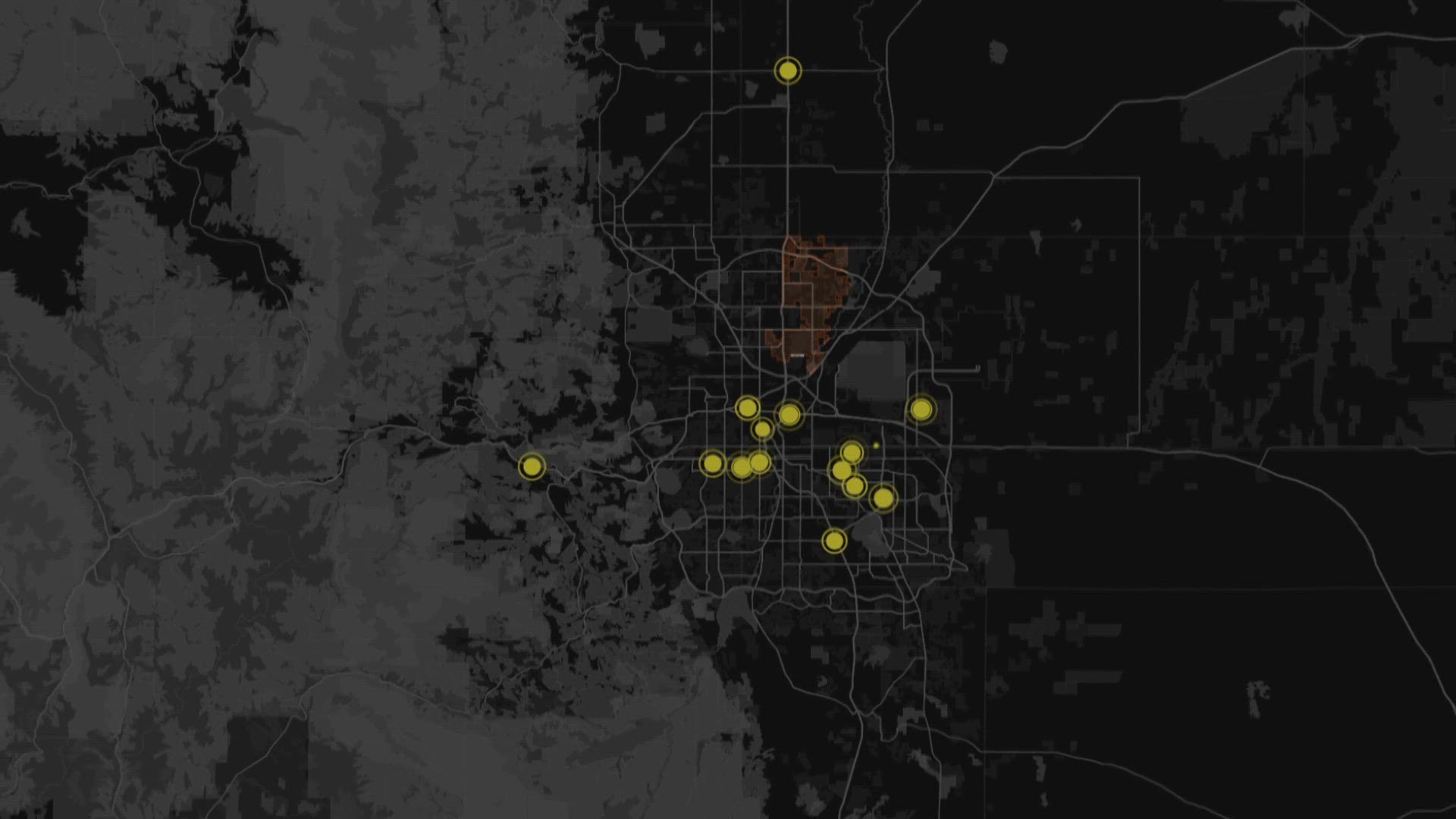

Over the past five years, the Colorado Bureau of Investigation documented 105 sustained NCIC misuse cases across the state.

9Wants to Know could only find two cases of law enforcement officers being charged over the last 10 years for violating NCIC rules---and those were federal cases.

Out of Denver’s 25 sustained cases over the past 10 years, most officers received a written or oral reprimand. Ten officers also lost up to one or two day’s pay. One officer was fired.

None of those DPD officers were criminally charged, including former cop Daniel Dunahue who looked up his ex-mistress after being accused of holding a gun to her head in a restraining order.

A CBI spokesperson said about 20,000 people currently have access to NCIC.

A victim’s perspective

“I was angry,” said a Denver area woman whose privacy was violated. She spoke to 9Wants to Know on the condition her name wouldn’t be revealed.

The woman received an anonymous, handwritten letter to her home, claiming she was on a police “scanner” and that she was “driving like a maniac.” The letter threatened she would be ticketed.

“For a long time I would walk outside of my house, I would look around, just to make sure things seemed okay,” she said.

Discipline documents reveal a mechanic obtained the woman’s address after he got his cop buddy, Denver Officer John Diaz, to run her license plate. Diaz received a written warning in the case.

“I don’t trust law enforcement like I used to,” the woman said.

Other NCIC abuse victims declined to speak to 9NEWS, fearing retaliation.

Police perspective: “We are somewhat unique”

“It’s wrong and we deal with it,” said DPD Deputy Chief Matt Murray. He said such criminal charges would be up to the district attorney.

Murray said the judicial system views police differently because they face stricter punishment at work compared to the average citizen. Murray said current internal discipline surrounding NCIC abuse is reasonable, because even a written reprimand can go on an officer’s permanent record, preventing promotions.

“It’s not an excuse, but we are somewhat unique because an officer faces double jeopardy in everything they do,” Murray said. “They could face criminal charges, but they definitely face departmental sanctions and sometimes those sanctions are much higher than people think.”

The Colorado Bureau of Investigation, which is responsible for overseeing NCIC use in Colorado, has a policy of relying on home law enforcement agencies to handle NCIC discipline.

A spokesperson for CBI said, typically, they would only launch a criminal investigation against an officer if they are requested by an agency to do so.

“You need to look at each case on its individual basis,” said CBI spokesperson Susan Medina, who echoed Murray’s reasoning.

When asked for how many people have been criminally prosecuted for NCIC abuse under CBI’s investigative authority, Medina provided one example of a state employee who was charged in 2014. That employee was not a law enforcement officer, she said.

“When you look at the full spectrum of actions that are available to a law enforcement agency, I would have to believe each agency is taking the necessary steps to take appropriate action,” Medina said.

A spokesperson for the Denver District Attorney’s Office said it reviews the egregiousness surrounding an NCIC violation, but that “a state criminal charge may not be filed if a harsher or more appropriate penalty comes from administrative discipline.”

Spokesperson Lynn Kimbrough could not say if her office reviewed any of the DPD officers with sustained violations, claiming they don’t “have a way to look up anything on cases we may have reviewed and declined. It would have to be a labor-intensive manual search of paper refusal slips that are in folders, chronologically by date.”

The Independent Monitor: Tougher Discipline Needed

In March, Denver Independent Monitor Nicholas Mitchell called for stricter discipline against DPD officers after his review of the 25 sustained cases involving NCIC abuse.

" ... each case risked potential harm to the reputation of DPD officers as trustworthy public servants, and in one case, the improper disclosure of NCIC/CCIC information created the opportunity for possible criminal behavior by a vengeful spouse,” Mitchell’s report said.

Mitchell’s call was met with no-change in the discipline matrix, which outlines what kind of sanctions an officer receives depending on a policy violation.

Deputy Chief Murray said at this current point in time, the discipline matrix reasonably handles NCIC discipline, what at its initial state is a Level 1 violation.

Murray stressed officers will often face stricter discipline for matters far more egregious than an NCIC look-up. It depends on how officers uses the information, Murray said.

“If somebody uses that information at a greater level, that’s going to prompt a bigger response.”

Civil Rights Advocates

“This opens a window to what is probably a more wide-spread problem than maybe we think,” said Denise Maes of the local ACLU. “I think a lot of us take too much comfort in the fact that this information is safeguarded, because that’s what the government and that’s what law enforcement, CBI, tell us all the time.”

Maes said she hopes the Denver Police Department will re-examine its discipline surrounding NCIC abuse.

“Outside some independent investigative body, the police will always whitewash any misconduct they engage in,” said David Lane, a civil rights attorney based in Denver. “This is like any other internal affairs investigation. When you have police investigating police misconduct, it generally goes pretty well for the police.”