CENTENNIAL, Colo. — Forensic serology – the analysis of biological evidence – has taken center stage at the trial of a man accused of beating a couple and their daughter to death with a hammer in January 1984.

Biological evidence is critical in the case – prosecutors need to convince the jury there is no innocent explanation for the presence of Alex Christopher Ewing’s DNA at the crime scene while defense attorneys need to cast doubts on the validity of that evidence.

It was against those competing interests that jurors have listened to hours of at-times tedious testimony about evidence in the case, and the effort to identify and understand the implications of blood and semen found at the scene.

Ewing, 60, faces multiple counts of first-degree murder in the killings of Bruce and Debra Bennett and their 7-year-old daughter, Melissa, who was also sexually assaulted.

During the passage of more than three decades from the crime to the time a DNA match brought Ewing into the sights of police investigators in 2018, the science of serology has evolved dramatically.

Back then, the idea of using DNA to identify the perpetrator of a crime was, in the words of one detective who has testified in the trial, “pie in the sky for law enforcement.”

Now, a genetic profile can be developed from a few skin cells or a drop of blood that can’t be seen by the naked eye.

And over the past two days, jurors in Ewing’s trial heard more than 3½ hours of detailed testimony from an expert in forensic serology who analyzed much of the evidence early in the investigation.

That included a section of carpet on which Melissa Bennett’s body was found, a comforter that covered her, and a napkin with blood on it discovered near a sink on the Aurora home’s second floor, where the bedrooms were located.

On the stand, Jeanne Kilmer, a longtime forensic serologist who was working at the Colorado Bureau of Investigation (CBI) in 1984, recounted going to the Bennett crime scene. There, investigators suspected the carpeting on which Melissa’s body was found may have had semen on it. Kilmer told jurors she personally cut the section of carpet from the floor and took it back to the CBI lab.

But her subsequent test for semen was negative – a point defense attorney Stephen McCrohan hit on in questioning her.

“You did your best work?” he asked her.

“Yes.”

“You were aware these were potentially important pieces of evidence?” he asked.

“All items of evidence are potentially important,” Kilmer answered.

There’s a reason McCrohan stressed the failure to locate semen on that carpet in 1984: Follow-up testing done in 1999 found semen on that section of carpeting, and the DNA profile it contained was eventually matched to Ewing in 2018.

Semen was also found on the comforter that covered Melissa – it, too, was matched to Ewing.

And while defense attorneys have suggested there could have been cross-contamination of evidence – and have raised issues about how it was handled, such as the fact many investigators didn’t wear gloves – under questioning from prosecutor Megan Brewer, Kilmer said the carpeting and the comforter were not packaged together and were not at the CBI lab at the same time.

Kilmer also testified at great length – she spent more than 3½ hours on the stand the past two days – about blood evidence.

McCrohan suggested in opening statements that a bloody napkin found on a vanity between Bruce and Debra Bennett’s bedroom and bathroom – and unidentified fingerprints discovered near it – cast doubt on the assertion that Ewing committed the crime.

That napkin, Kilmer said, had blood on it consistent with Bruce Bennett’s. McCrohan has suggested that the killer used that napkin to wipe blood from his hands, then tried to wash up at the nearby sink, leaving fingerprints on the faucet handle.

The person those fingerprints belong to has never been identified.

Kilmer was followed to the stand by longtime police detective Marvin Brandt, who was called to the Bennett home the day the bodies were discovered and later served as the lead detective on the case. He testified at length about various steps he took in the case, including an effort in 1988 and ’89 to go through all the evidence – a process carried out in a secure room in the building where the police department stored evidence.

But McCrohan got him to acknowledge that he sometimes laid out evidence on tables that hadn’t been covered with sterile paper, that he didn’t sanitize a tape measure that was photographed on multiple pieces of evidence, and that the wrapping covering some pieces of evidence had been opened by other investigators and not properly resealed.

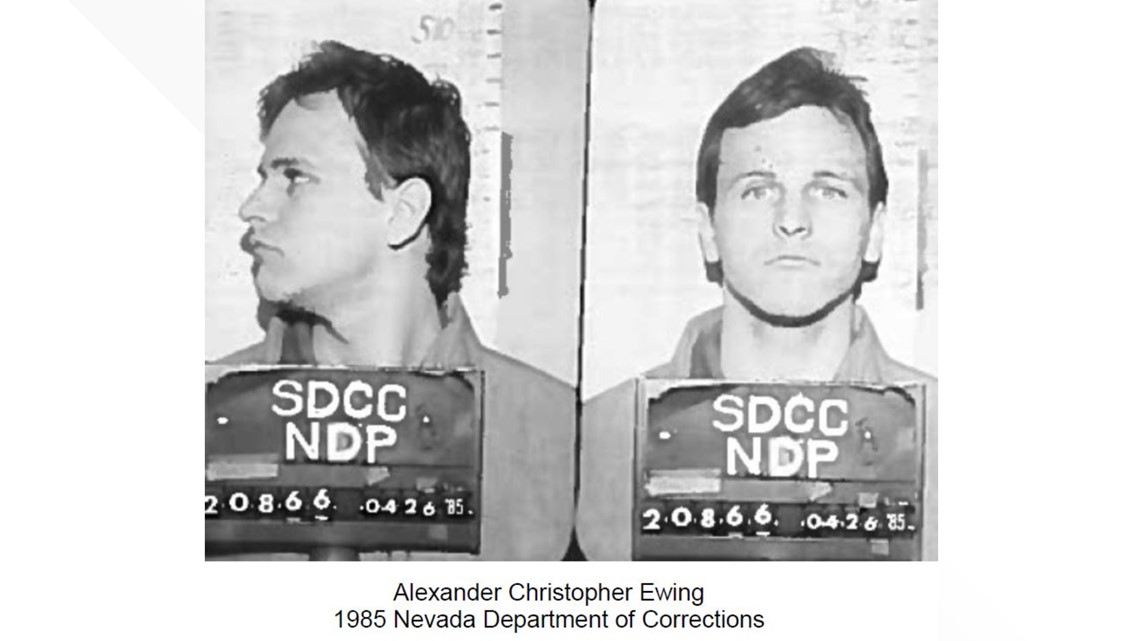

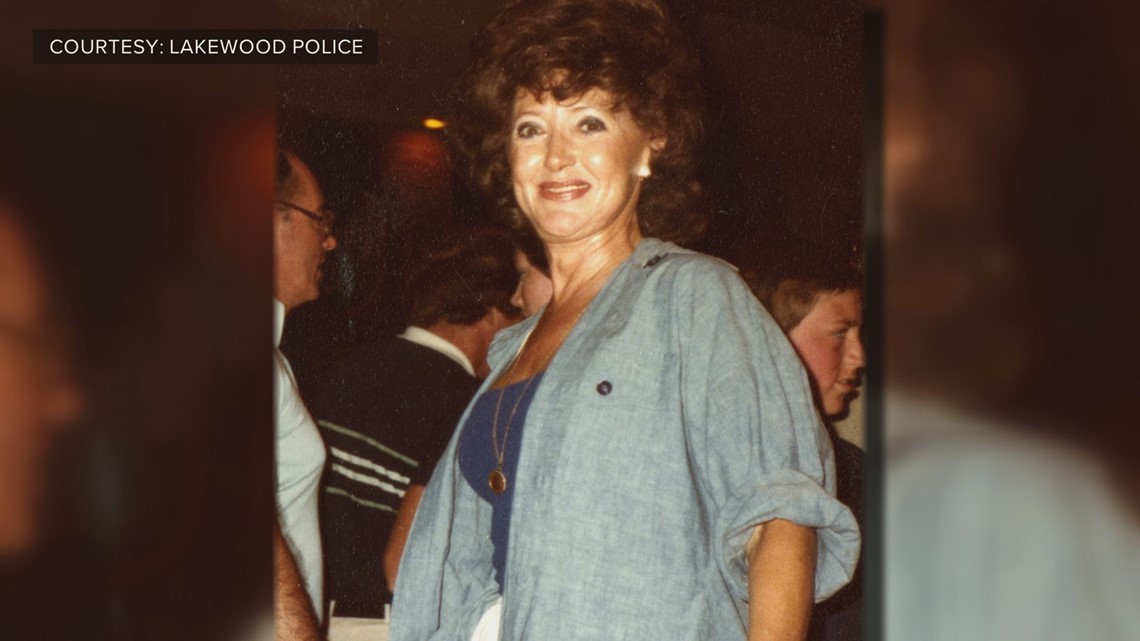

At the time Ewing was identified as a suspect in the Bennett killings – and the murder the previous week of Patricia Smith in Lakewood – he was behind bars in Nevada, serving a sentence for a late-night ax handle attack on a couple in Henderson. That assault occurred about seven months after the Bennett and Smith murders.

Ewing is scheduled to go on trial in Smith’s murder in October in Jefferson County.

Contact 9NEWS reporter Kevin Vaughan with tips about this or any story: kevin.vaughan@9news.com or 303-871-1862.

The story of the assaults, the search for a killer, and the anxiety that gripped the survivors and altered life in the Denver metro area is the subject of a 9Wants to Know investigative podcast.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Bennett family murders