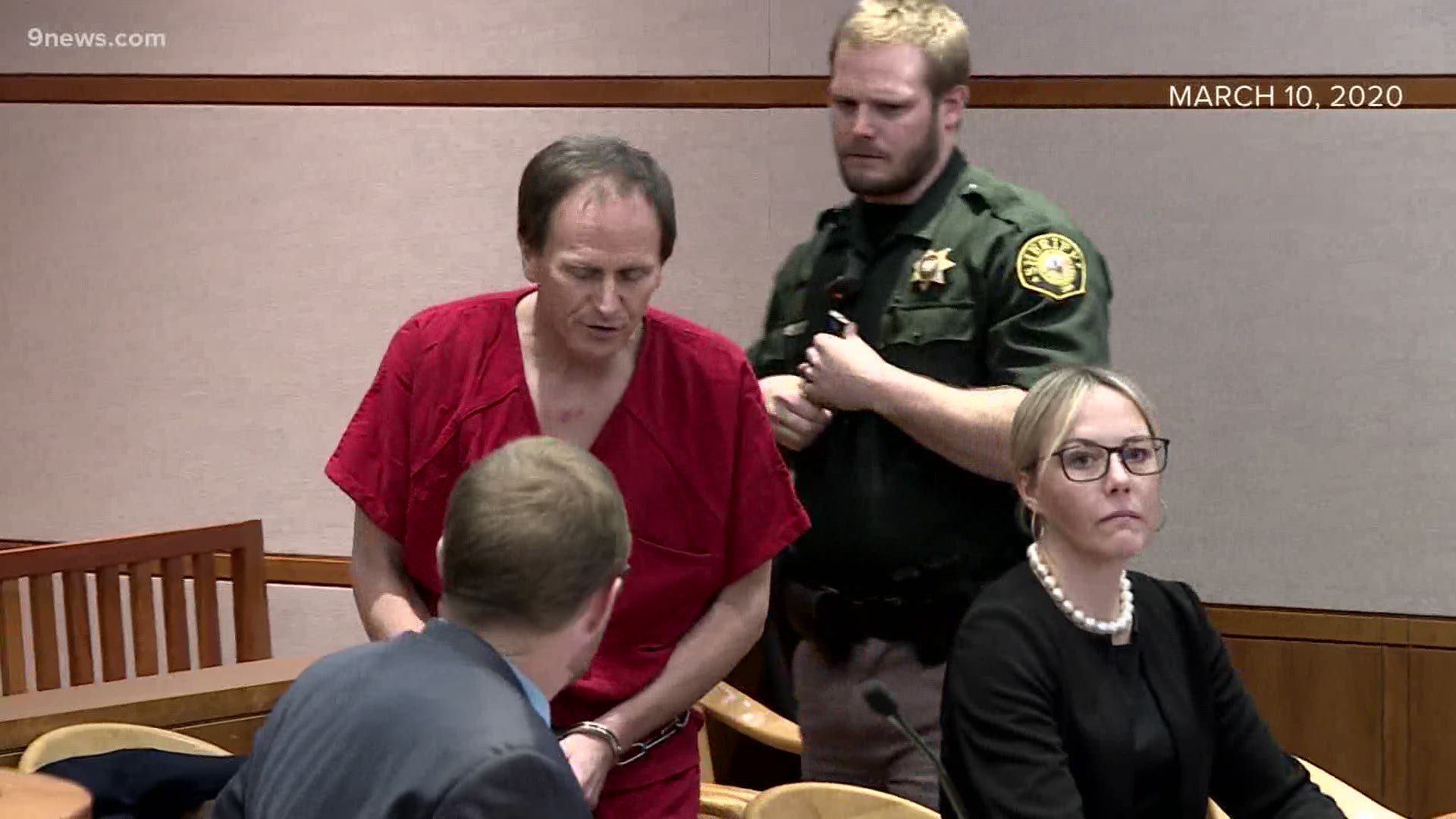

ARAPAHOE COUNTY, Colo. — Attorneys for the man accused of murdering three members of an Aurora family with a claw hammer raised questions Thursday about whether police investigators mishandled evidence in the shocking case.

The questions came during the second day of depositions of witnesses in the case of Alex Christopher Ewing – and they were initially directed at a retired Aurora police officer who was the original lead detective in the Jan. 16, 1984 attack that left Bruce and Debra Bennett and their 7-year-old daughter, Melissa, dead. A younger daughter, 3-year-old Vanessa, critically injured.

Ewing is scheduled to go on trial April 19. However, the case has been beset by delays, and with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic more are possible. As a result, Arapahoe County District Judge Michelle Amico allowed prosecutors and defense attorneys to take video-recorded testimony now from several older witnesses that could be played for a jury if they are unable to testify later.

Defense attorney Katherine Spengler zeroed in on the handling of evidence when she cross-examined former Aurora police officer Wilson Egan, pointing to a blood-stained pair of jeans that were found in the home’s master bedroom.

Egan responded to the scene the day the murders were discovered and was the lead investigator on the case for about two years.

RELATED: Woman recounts discovering that her son, his wife and daughter had all been bludgeoned to death

RELATED: Judge: Hammer murder suspect won't face death penalty in 1984 killings of 3 members of family

“Those jeans were not collected right away, correct?” Spengler asked the retired officer.

“If they weren’t, I’m not aware of that,” Egan replied.

The jeans had originally been seen on the floor in the bedroom near Debra Bennett’s body, but someone placed them in a hamper before they were booked into evidence.

After providing Egan with a report to refresh his memory, he acknowledged that the jeans – and a towel with blood on it – weren’t collected until six days after the killings.

Spengler also asked about the handling of a small retractable knife originally seen near the body of Melissa Bennett – which prosecutors surmise the killer used to cut off the girl’s pajamas. When the knife was collected, it had been moved by someone to the top of a dresser in the room.

There was no indication in the report on the collection of the knife that it had originally been seen on the floor.

And later, Spengler noted that in April 1986 Egan and other investigators were notified that the knife could not be located in the warehouse where the department stored evidence.

“The minute we were made aware of it having been misplaced we went over there … and found it,” Egan said.

He said it was located inside an evidence envelope in a box.

Spengler also questioned Egan about the security at the crime scene in the initial hours.

“Can you estimate how many people were inside the home?” she asked.

“No,” Egan replied.

“Because you hadn’t established scene security yet?” she asked.

“No,” he said.

However, under follow-up questioning by prosecutor Megan Brewer, Egan said the scene could be entered only by authorities – there was evidence tape up around the home, and “there were numerous police officers present.”

“You couldn’t walk through the scene, no,” Egan said. “There was scene security 24 hours a day, seven days a week.”

He also said the collection of evidence six days after the killings was during the time period that crime scene investigators were still working in the home – and that the warehouse where the evidence was stored was secure and not open to the public.

Later, defense attorney Stephen McCrohan raised similar issues with retired crime scene technician Walter Moeller, who was among those responsible for photographing and collecting evidence inside the Bennet home.

McCrohan wasted no time pointing to the practices in place 36 years ago.

“When you went to the Bennetts’ home and collected all this evidence, were you wearing gloves?” McCrohan asked.

“No,” Moeller replied.

“In 1984, was it pattern and practice when you went to a crime scene to collect evidence to wear gloves?” McCrohan asked.

“No,” Moeller said.

Moeller acknowledged there were times when he touched one piece of evidence with his bare hands and then another. He acknowledged leaving a palm print on the window sill in the bedroom shared by Melissa and Vanessa Bennett. And he acknowledged that a police lieutenant brought a group of recruits through the crime scene but said he does not know many they were – or who they were.

McCrohan asked him about discrepancies in markings on a number of pieces of evidence.

Debra Bennett’s purse, for instance, was found in front of the home the day the murders were discovered, and Moeller tagged it and put it in an evidence bag that day. But the bag wasn’t booked into the evidence room until nearly a month later, on Feb. 15, 1984, according to markings on the bag. At the same time, reports show that detectives opened the purse on Jan. 30, 1984, and did an inventory of the contents – but there are no markings on the bag showing that it was opened and re-sealed.

In another line of questioning, McCrohan showed that numerous pieces of evidence from the home were marked as having been collected on Feb. 14, 1984, long after crime scene technicians had finished in the Bennett home.

“Sir, were you at the Bennett residence on Feb. 14, 1984?” McCrohan asked.

“No,” Moeller answered.

That question and answer was repeated multiple times.

None of the questions dealt with the evidence that identified Ewing as a suspect more than three decades after the killings: DNA.

It was a DNA hit in the summer of 2018 that linked Ewing, then behind bars in Nevada serving a sentence for a 1984 ax-handle attack on a Henderson couple, to thee long-unsolved killings of the Bennetts and Patricia Louise Smith in Lakewood.

He’s scheduled to be arraigned Feb. 26 in the Smith case.

Contact 9Wants to Know investigator Kevin Vaughan with tips about this or any story: kevin.vaughan@9news.com or 303-871-1862.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Investigations from 9Wants to Know