CENTENNIAL, Colo. — After several hours of deliberations, Thursday afternoon the jury deliberating the fate of the man charged in the 1984 killing of three members of the Bennett family told the judge they're "at an impasse". The judge, in turn, said it was "too early" to declare a mistrial and sent jurors home for the night

They're set to return to continue deliberations on at 8:30 a.m. on Friday.

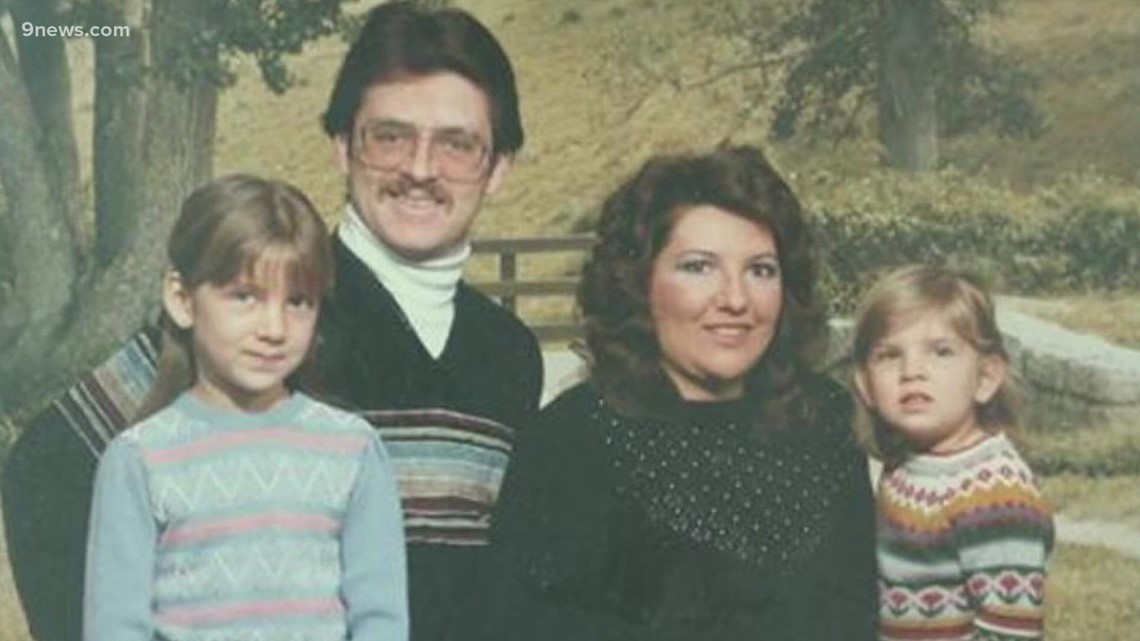

Earlier in the day, Prosecutors and a defense attorney laid out competing narratives for the jury that will decide whether Alex Ewing is guilty of multiple counts of first-degree murder in the slayings of Bruce and Debra Bennett and their daughter, Melissa, in January 1984.

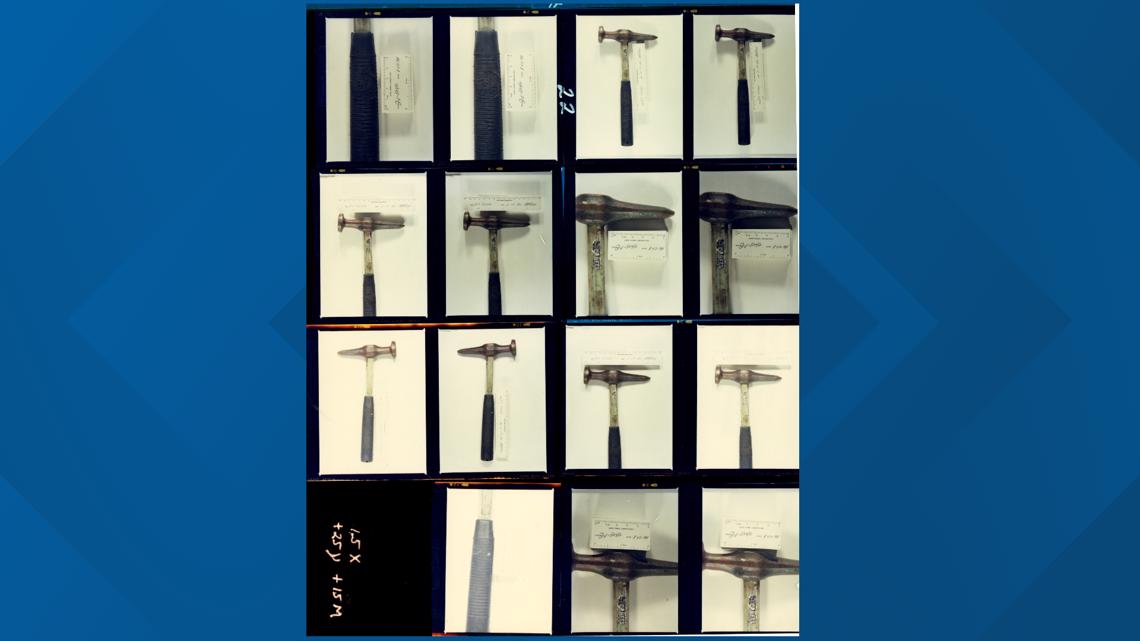

Ewing either brutally beat three members of an Aurora family to death with a hammer and raped a 7-year-old girl – or he’s the victim of a police investigation marked by mistakes and mishandled, lost, unexplained and untested evidence.

On one side, the jurors heard there is “no innocent explanation” for the presence of Ewing’s DNA on the carpeting where Melissa was raped and killed. On the other, jurors heard that “it’s just not that simple” that Ewing, and Ewing alone, committed the crimes.

The day had begun with the anticipation that defense attorneys Stephen McCrohan and Katherine Spengler could call at least one more witness – but that didn’t happen.

9WTK will have a special live stream on the trial following closing arguments on Thursday, August 5. If you have a question for Kevin Vaughan text it to 303.871.1491 and he will answer it following closing arguments.

“The defense rests,” Spengler told District Judge Darren Vahle after the jury was brought into the room a little after 8:30 a.m.

Ewing, who decided not to testify, wore a gray long-sleeved dress shirt and a maroon tie.

Ewing, 60, was behind bars in Nevada in the summer of 2018 when his DNA was matched to genetic material left inside the Bennett home in the 16300 block of East Center Drive – breaking open a case that had stumped investigators for more than three decades.

That DNA was the heart of the prosecution’s case.

They brought in multiple witnesses who testified that a DNA profile found from carpeting beneath Melissa Bennett’s body and a comforter that partially covered her matched Ewing. That DNA was extracted from sperm.

The defense acknowledged that DNA match but brought in witnesses whose testimony illustrated the fact that many of the original investigators failed to wear gloves and raised questions about the way evidence was stored and tested over many years.

They also raised questions about evidence that no longer exists.

For example, a hair found on Melissa Bennett’s pajamas that may have been left by the killer was destroyed in testing in the 1980s, and swabs and other evidence taken during the girl’s autopsy are gone – either because they were rotting and were destroyed, or because they were somehow misplaced.

McCrohan and Spangler suggested more than one person committed the crime and elicited testimony that none of the fingerprints found in the Bennett home was matched to Ewing. They questioned the failure by investigators to conduct “touch DNA” testing on evidence in the case, including the handle of a knife the killer is believed to have used to slash Bruce Bennett’s throat.

Closing arguments marked the last chance for each side to make an impression on the jury – and an opportunity to weave the testimony of the 34 witnesses into a coherent account of what the evidence could mean.

District Attorney John Kellner spoke first in the hushed courtroom.

“Thirty-seven-and-a-half years ago, under the cover of darkness, this defendant, this man, Alex Ewing, crept into the Bennett family home and snuffed out the life of a young family,” Kellner said, his voice rising with each sentence. “He brutally murdered Bruce Bennett, crushing his skull. He brutally attacked and murdered Debra Bennett, crushing her skull. And he raped and murdered a 7-year-old child.”

And then, Kellner said, Ewing fled – no idea that he’d left behind evidence that would one day identify him.

“He cannot walk, run or hide from the advances of science – that this man, to the exclusion of all other people in this world, left his semen behind after raping Melissa Bennett to death and killing her family,” Kellner said.

Kellner walked the jury through the crime – to the killings, the discovery of the bodies, and the horrific wounds they suffered.

He detailed the elements of the crime necessary to convict Ewing.

In all, Ewing faces six counts of first-degree murder in the Bennett killings. Three of the counts allege that he killed Bruce, Debra and Melissa Bennett after deliberation. Three of the counts allege that he killed each of the victims while committing another serious felony – including the sexual assault of Melissa Bennett and the burglary of the family’s home.

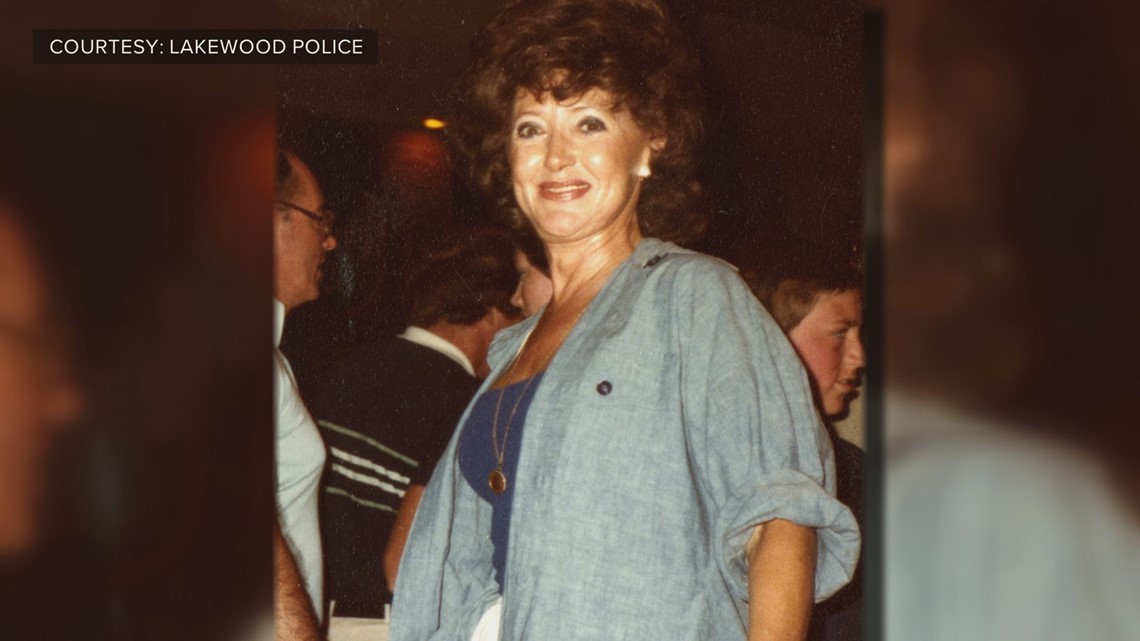

Kellner reminded them that Ewing’s DNA was found in the Lakewood townhome where Patricia Louise Smith was raped and beaten to death with an auto-body hammer. That killing occurred six days before the Bennetts were killed.

A judge ruled that the jury could be told about Smith’s killing for limited purposes – “proving identity, for showing modus operandi and common plan, scheme, or design, and to refute any defense of mistake or accident as associated with the DNA evidence.”

Kellner reminded the jury of the similarities between the two crimes – at both homes, the killer is believed to have entered through an open garage door, emptied purses and wallets, surprised the victims, used a hammer as a weapon, and committed violent rapes, leaving his victims partially clothes, on the floor, with their legs spread apart and their faces covered.

“This is the defendant’s signature move,” Kellner said. “He did it at the Smith house, and he used that same M.O. at the Bennett house.”

He suggested the lack of fingerprints was easily explainable – the killer wore gloves. And he argued that testimony and evidence made it inescapably clear that none of the evidence that yielded DNA was compromised in any way.

Testing, he reiterated, conducted at different times over many years, located Ewing’s DNA not only on the carpet and comforter from the Bennett home but also on carpeting and a blanket at Smith’s home. And, he told the jury, there was no cross-contamination between the cases – there was no DNA from any of the Bennett’s on evidence in the Smith case, and there is none of Smith’s DNA on any of the evidence in the Bennett case.

“It’s the defendant’s DNA and it’s the defendant’s M.O. in both cases,” he said.

Ewing, he said, was in Colorado until just 11 days after the Bennett murders, lived not far from the family’s home, worked on a plumbing crew with access to “the implements of murder” and could have worn the type of work boots that left bloody footprints at the scene – and left his DNA all around Melissa Bennett.

“There’s a reason for that,” Kellner said. “Because he’s guilty.”

He said for Ewing to have to be innocent would require the conclusion that he was the “most unlucky man in the world.”

After a break, McCrohan stepped before the jury, the flat screens in the courtroom displaying the words, “Alex Ewing is not guilty.”

“Alex Ewing is not guilty,” McCrohan began. “It’s simple. What the government needs you to believe, the story they need you to believe about what happened in the Bennett home, that it was Alex Ewing and Alex Ewing alone that committed this crime. But you’ve seen the evidence in this case, and you’ve seen that it’s not that simple.”

He urged the jurors to look at the evidence – and the evidence prosecutors decided not to introduce. Do that, he told the jurors, and “you will find that does not equal proof beyond a reasonable doubt.

It is not proof beyond a reasonable doubt because Alex Ewing didn’t do this,” he said.

He told the jury one thing is not in dispute.

“What happened to the Bennett family was horrible,” McCrohan said. “What Connie Bennett had to suffer, no person, no mother, should ever have to go through. What Vanessa Bennett has suffered, no person should have to go through.”

None of that, he said, was in dispute.

“What we’re challenging is who did it,” he said.

He accused prosecutors of failing to do “touch DNA” testing of numerous pieces of evidence. Those included the knife the killer used to slash Bruce Bennett’s throat, Debra Bennett’s purse, Bruce Bennett’s wallet, two drawers pulled out in the kitchen, Melissa Bennett’s underwear and pajamas and a knife found underneath her body.

“All of these things likely have the skin cells of the person who did it,” McCrohan said.

That testing wasn’t done, a prosecution witness said, because looking for touch DNA in cold cases has proven to be a waste of time because of the way evidence was handled decades ago, which often left it contaminated with genetic material, sometimes from gloveless investigators.

McCrohan hit on that failure, arguing that even if touch DNA testing showed genetic material from investigators or others it would still be valuable information.

“They can figure that out if they want to,” he said. “Or they can stick their head in the sand and say nobody knows.”

McCrohan reminded the jurors about the dozens of fingerprints from the Bennett home that have never been identified – and that none of them were Ewing’s.

RELATED: Ewing says he won't testify, as defense notes fingerprints found in Bennett home aren't his

And he suggested, again, that unidentified fingerprints on an upstairs faucet were left by someone “who had blood on their face or hands, attempting to clean up.”

McCrohan reiterated police failings – such as a supervisor’s decision to give a group of cadets a tour of the Bennett crime scene. During that tour, someone moved a pair of bloody jeans and a blood towel from the floor to a clothes hamper.

And he hit on the DNA results.

“You don’t have any information about when that semen was left on that carpet and comforter,” he said.

Underscoring that point, he suggested the destruction or loss of swabs from Melissa Bennett’s vagina left a big, unanswered question – was there semen in her body matching what was found on the carpeting.

“There’s no evidence before you those match the carpet,” McCrohan said. “They might. They might match the carpet. They might match someone else.”

When he turned his attention to Smith’s murder, he focused on the failure to find Ewing’s DNA on the hammer that killed her or on her bra, underwear, jeans, blouse, sweater, boots, or billfold.

And, as in the Bennett killings, none of his fingerprints were found at the scene.

Like Kellner, he talked to the jurors about the burden of proof – which rests on the prosecution – and the fact the defense does not have to explain anything.

“I get worried about the burden of proof and I get worried because you all might be back there thinking, well, they didn’t give us an innocent explanation for the semen,” McCrohan said.

He urged them to consider the lack of evidence.

“Ladies and gentlemen, Alex Ewing is not guilty,” McCrohan said. “Alex Ewing did not commit the crime. The reason this evidence doesn’t add up, the reason you don’t have answers to all these questions is because he did not do it. We’re asking you to find him not guilty of all these crimes.”

The prosecution got the last word.

“There is no innocent explanation,” prosecutor Garrik Storgaard said. “There is absolutely no innocent explanation about how that man’s sperm is underneath Melissa Bennett’s raped body. There is no innocent explanation about how that man’s sperm got on the comforter. There is no innocent explanation how that man’s sperm got inside Patricia Smith, underneath her, or on the blanket that covered her.”

Storgaard dismissed the value of touch DNA – noting that his own pen might not have his profile on it but contain genetic material from others.

The DNA in the Bennett case, he reminded the jury, came from sperm.

“You don’t need a biology lesson to know how that happens,” Storgaard said. “The defendant didn’t just accidentally deposit his sperm on a 7-year-old girl. The defendant didn’t just accidentally deposit his sperm on a raped and murdered Patricia Smith.”

Skorgaard walked within a few feet of Ewing, with a photo of the Bennett family on the screen behind him.

“In 1984, this man right here massacred this family,” Skorgaard said. “But he left a key. He left a key to his identity. He left a genetic key – his sperm.”

At 12:08 p.m., Storgaard finished, and a few minutes later the case went to the jury of six men and six women.

Nearly 50 people were in the courtroom for closing arguments – a stark difference from much of the trial when the gallery was occupied by a dozen or so people at most times.

Bruce Bennett’s mother, Connie Bennett, sat in her usual seat in the front row, flanked by her sister, two of her children, and other family members.

Connie Bennett had gone to her son’s home after he and his wife had failed to show up at work on Jan. 16, 1984, and discovered the horrific scene.

Also in the courtroom were the victims of two other attacks that police suspect Ewing in – but that he has not been charged with.

One was a woman who, along with her then-husband, was attacked by a man with a hammer on Jan. 4, 1984. The other was a woman who was beaten, sexually assaulted and left for dead late on Jan. 9, 1984, or early the next morning.

The first police officer who arrived at the Bennett home after Connie Bennett’s call for help was in the gallery.

So were Jefferson County prosecutors handling the case against Ewing in Smith’s murder. He is scheduled to go on trial in that case on Oct. 18.

Contact 9NEWS reporter Kevin Vaughan with tips about this or any story: kevin.vaughan@9news.com or 303-871-1862.

The story of the assaults, the search for a killer, and the anxiety that gripped the survivors and altered life in the Denver metro area is the subject of a 9Wants to Know investigative podcast.

“BLAME: The Fear All These Years” takes listeners back to the attacks and tells the stories of those most deeply impacted — the survivors and the loved ones of the dead. It follows the police investigation through years of cold-case frustration, forensic breakthroughs and the latest developments.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Bennett family murders