40 Years in the Dark: How genetic genealogy solved the Helene Pruszynski murder case

Authorities found Helene's killer using science that couldn't have been imagined even a few years ago.

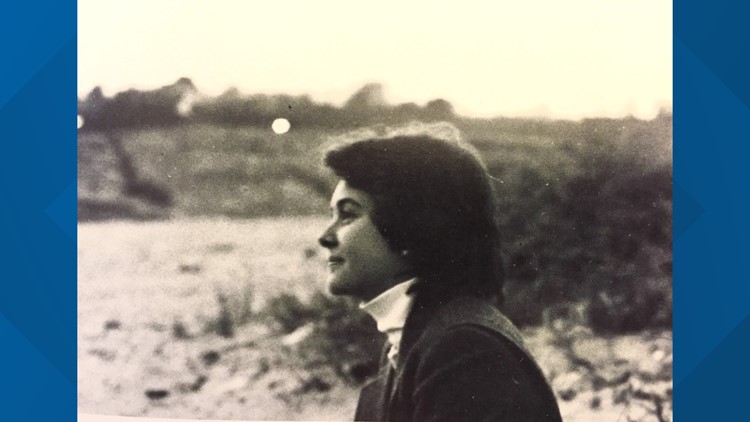

Courtesy Janet Pruszynski Johnson

Just after 10:30 the chilly night of Jan. 16, 1980, Englewood police officer Richard Welbourne looked at a Polaroid photograph of a woman with a thousand-watt smile, turned it over, and wrote out a shorthand-description in a ball-point pen.

- 5’ 100, Brn, Blue,

- Blue Coat

- Lt Tan Cord Type Pants

- Grn Sweater Over White

- Turtle Neck.

- Lace Type Brn Shoes

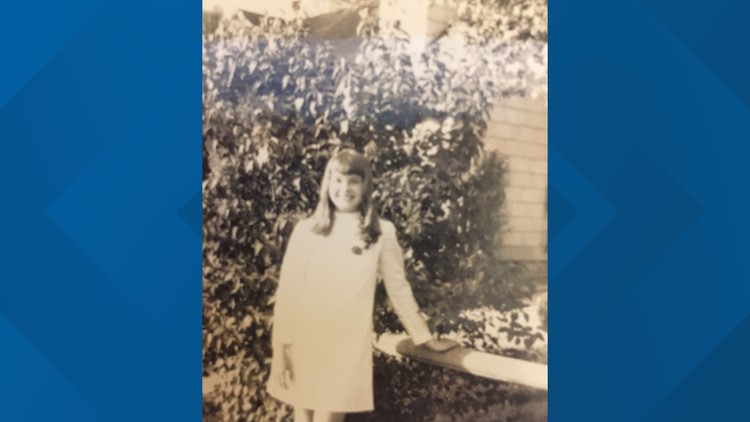

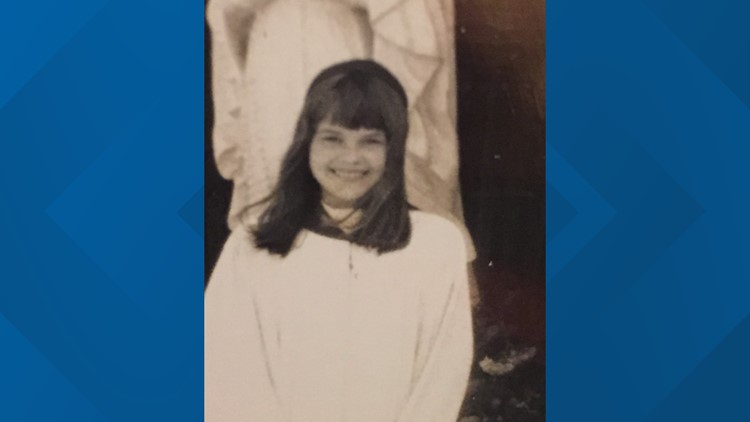

The woman in the picture was 21 years old. Her name was Helene Pruszynski. She was a senior at Wheaton College in Massachusetts who had come to Denver with a classmate after they’d both been selected for internships. Helene, an aspiring journalist, was working in the news department at K-H-O-W radio. The day before, she’d covered a big story – the aftermath of the fatal shooting of a Secret Service agent inside the Denver field office.

Now, Helene was missing.

Her shift at the radio station had ended at 5:30 p.m. Responsible and punctual, she followed the same routine every day. Walk two blocks from the radio station’s office to the corner of 14th Avenue and Broadway. Climb onto an RTD bus for the trip to Englewood. Get off in front of Frank the Pizza King near the corner of Union Avenue and Broadway. Walk six blocks to the home of her aunt and uncle, where she and her classmate were staying.

She should have been home by 6:30 p.m.

Worry quickly overtook Helene’s aunt and uncle and her friend, Kitsey Snow. They’d driven to the bus stop, driven up and down Broadway, and called the radio station. They’d called the police. They’d walked the nearby streets, looking for something – anything – that might tell them where Helene was. Back at the house, Kitsey had written in her journal.

"Poor Helene. What is she going through? Where is she? Is she alright? … I can’t believe this is happening. I keep telling Aunty Wanda not to worry or imagine the worst which is of course what I am doing."

Helene was four hours overdue when Officer Richard Welbourne arrived to take a missing persons report. Nobody – not the people who loved Helene, not the generations of detectives who would work to solve the case – could have imagined it would be nearly 40 years before there would be an answer.

And it was an answer that would only come after decades of advances in forensic science, and only because creative detectives figured out a new way to use it.

Baseball, music and journalism Helene's early years

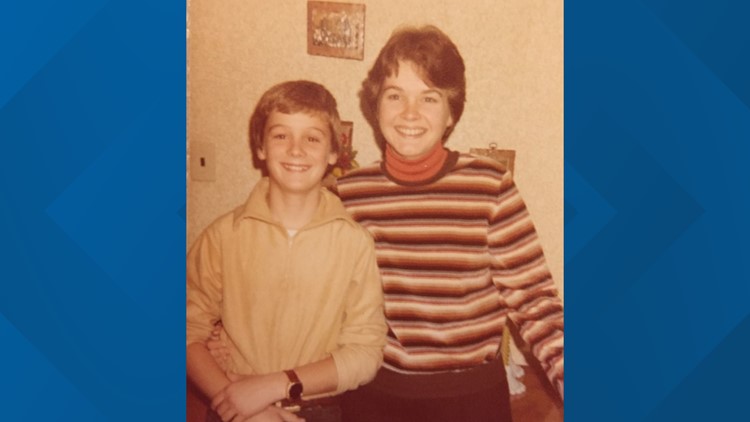

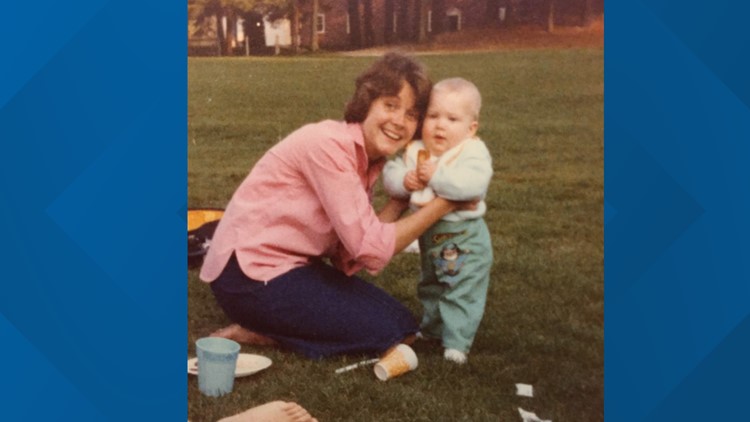

Helene Pruszynski spent the first part of her life in South Huntington on Long Island – the youngest of three children of Chester Pruszynski, an Army veteran and engineer, and his wife Henrietta. Her sister, Janet, was nine years older; her brother, Chet, 12 years older.

Helene fell in love with baseball, rooting for the New York Mets, memorizing all the team’s players and their positions.

Then her father took a new job in 1972, and moved the family to Hamilton, Mass., at the time a town of fewer than 7,000 northeast of Boston.

Helene traded in her love of the Mets, adopting the Boston Red Sox.

In high school, she was active in music and stage.

At Wheaton College, she studied journalism – and was thrilled when she landed that radio station internship.

“She just was an eager beaver, go-getter in college, you know?” her sister would say many years in the future. “She was a strong person and she got involved – she made things happen.”

PHOTOS: 40 Years in the Dark: The 1980 Helene Pruszynski murder case

'There's a body out there' Promising crime scene turns cold

Around 9 a.m. the morning after Helene’s disappearance, a woman driving along Daniels Park Road in northern Douglas County heard her 13-year-old son call out: “Mom – there’s a body out there.”

She glanced into the lonely field of brown scrub with patches of snow here and there. It did look like a body.

The woman flagged down the operator of a road grader, who went to investigate.

When he was 10 feet away, he knew. It was a woman, and she was dead.

Over the next two hours, investigators from the Douglas County Sheriff’s Office and the Colorado Bureau of Investigation swarmed the field.

Almost immediately, they knew the woman had been brutalized – sexually assaulted and stabbed to death, her hands bound behind her with nylon straps. Her identity was settled nearly as quickly – an Arapahoe County sheriff’s deputy, who worked part time at K-H-O-W, arrived at the scene. He knew he was staring at the body of Helene Pruszynski.

Detectives worked the scene carefully, looking for evidence. In the dirt along the edge of the two-lane road, they noticed tracks left by a vehicle, and footprints – two sets of them in the snow leading out into the field; one set, apparently from cowboy boots, returning.

They gathered everything they could find that might help them figure out who did such an awful thing: an empty milk carton, a hunk of bread, an old can. They snapped photographs and made plaster casts of the tire tracks and the footprints.

And they got lucky.

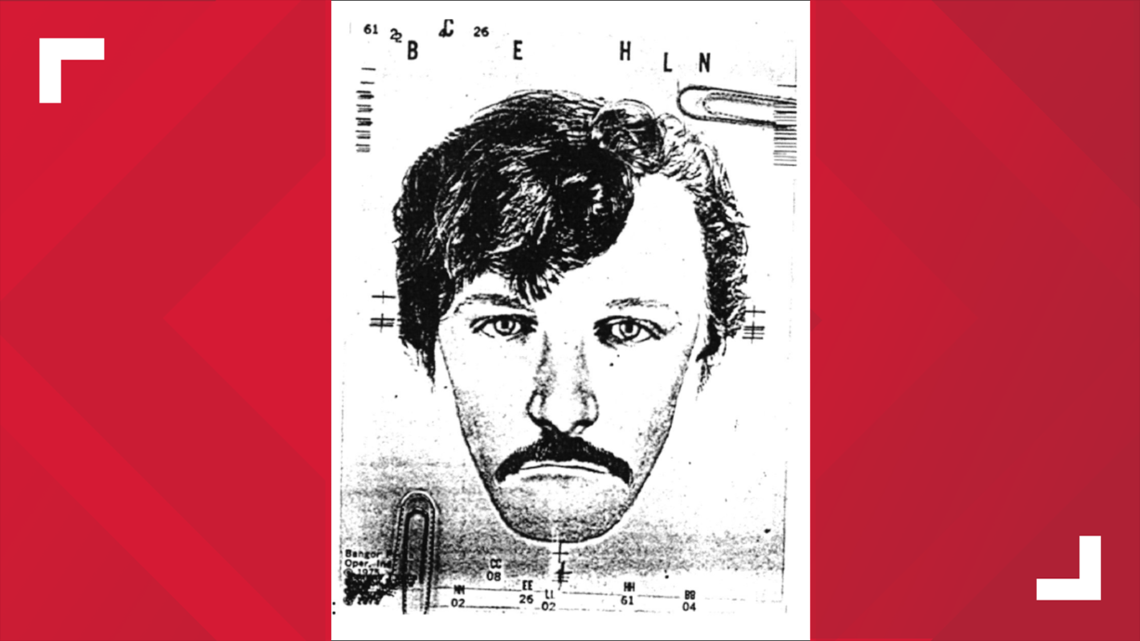

After the news broke, a woman came forward with a remarkable story. She’d been driving along Daniels Park Road around 10:20 the night Helene disappeared and had seen a man in the area where her body would be discovered. She provided a detailed description – 20 to 30 years old, possibly Caucasian, medium-length brown hair “over the ears,” possibly wearing a mustache. Under hypnosis, the woman recalled more details. An artist drew a remarkably realistic composite of a possible suspect.

Detectives also had a theory. A woman had been raped not far from where Helene should have gotten off the bus a couple weeks earlier. The very night she vanished, another woman had been accosted in the street. It seemed likely that those cases might be related to Helene’s disappearance and murder.

But the investigators also faced a huge handicap: Helene had been in Colorado less than three weeks, and it was likely she was attacked by a stranger – the most difficult kind of case to solve.

“We’re doing everything we can to run down leads,” said Carl Whiteside, deputy director of the Colorado Bureau of Investigation. “But after that, you know the way it goes. Especially when the victim is new in town.”

The following year, the investigation into her murder went cold. It lay dormant for nearly two decades.

No match Case re-examinations turn up no leads (at first)

When Helene Pruszynki was murdered in 1980, the idea that the killer had left behind DNA that could identify him was still years in the future. By 1998, that future was in full bloom.

That year, Tony Spurlock, now Douglas County’s sheriff, Holly Nicholson-Kluth, the current undersheriff, and Capt. Bill Walker re-opened the investigation. They formed a task force that included investigators from the Englewood Police Department and the Colorado Bureau of Investigation who went through all the evidence, learning that none of it had ever been tested for DNA.

That testing yielded a genetic profile of the killer. But after it was uploaded to the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System – a repository of millions of profiles from both known criminals and unsolved crimes – there was only disappointment.

There was no match.

The case was re-examined again in 2000, 2005, 2010 and 2013, when that DNA led to eight women who may have been related to the killer. The follow-up investigation went nowhere.

In 2017, detectives began yet another look at the case, hoping for a breakthrough.

A DNA revolution Home DNA kits bring new leads for investigators

Beginning with its widespread use to solve crimes in the late 1980s, detectives found DNA both tantalizing and defeating.

If they put a profile in the FBI database and got a hit, or tested a sample from a crime scene against a suspect and got a match, they were almost always on the doorstep of solving the case.

If they didn’t, it was just another piece of evidence that they couldn’t fit into the puzzle before them.

This happened even as science marched on and DNA could be extracted from smaller and smaller samples – eventually even from a hair, and then from a few skin cells. But even with those advances, cases often stalled out when they couldn’t find a match.

Then came the home DNA kit revolution – millions of people testing themselves, hoping to learn about their ancestry, track down long-lost relatives or find birth parents. And eventually, investigators realized that even if they couldn’t take DNA from a crime scene and find a killer, they could use the sample to find the killer’s relatives.

Genetic genealogy was born.

Here’s how it works: Detectives take a DNA sample from an unsolved crime and upload it into an open-source database, such as GEDmatch. If they’re lucky, they’ll be provided a list of people related in some way to the killer. From there, they build a family tree – and, if everything goes well, they’ll end up with the killer somewhere in the mix.

Then it becomes a matter of old-fashioned detective work. Is a suspect the right age? Was he in the area where the crime occurred and when it occurred? Does he have an alibi?

That’s the work that Douglas County sheriff’s investigator Shannon Jensen pursued, beginning in 2019

It can be daunting – when Jensen first ran the killer’s DNA through the genealogy site GEDmatch, she got 3,000 hits – 3,000 people who shared some genetic connection to the man detectives had been hunting for nearly four decades.

“There are some that are so far back – you know, eighth generation, seventh generation, sixth generation,” Jensen said. “They’re important, but they’re not very useful to a detective in solving a case like this.”

But as she worked her way down the various branches in the massive group of people, she got to people closer to the killer. She reached a distant cousin, who had access to profiles for family members Jensen had not found.

“I was able to contact those people who had already done an Ancestry or a 23andMe DNA kit,” Jensen said. “They were willing and able to upload those to that public database.”

That took her closer – to two relatives in particular. Jensen, who had never been on a case like this one before, worked with – and learned from – a genealogist, Joan Hanlon of United Data Connect.

There were false starts. She and other detectives went to Arizona to follow one possible suspect. Jensen, working undercover, saw the man toss a water bottle into a trash can, grabbed it later and sent it to the lab. No match.

Later, she zeroed in on a man named William White Jr., a man with a history of “deviant sexual behavior.” The DNA from Helene’s body and clothing was compared against White’s. Again, no match.

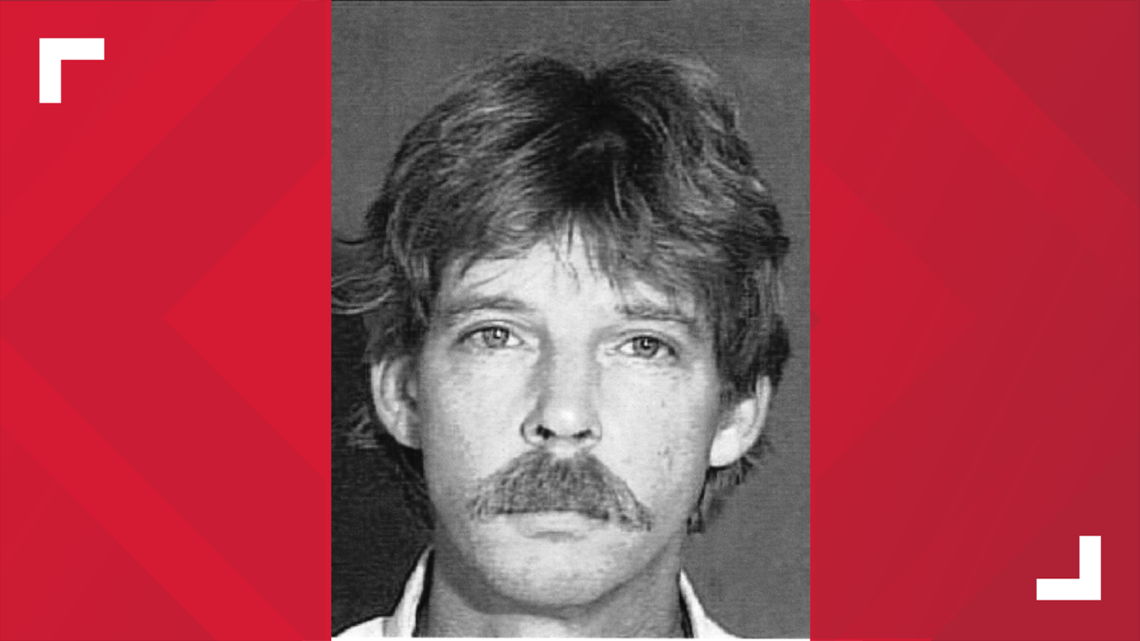

Then Jensen turned her attention to his younger brother, Curtis Allen White – a man who’d been convicted of raping a woman at knifepoint in Arkansas in 1975, who’d come to Colorado in 1979, and who’d started going by a new name in 1982: James Curtis Clanton.

As Jensen put together the details of his life, she was sure she had found Helene Pruszyinski’s killer. She went to Lt. Tommy Barrella, an experienced officer new to cold case work.

“We have this thing,” Jensen said. “He has to have his coffee before he can really talk to anybody, and I was shaking with adrenaline, and I said, 'I know who he is.' And he's like, 'What?' I said, 'I know who he is.'”

At that point, Jensen needed only one thing: A sample of Clanton’s DNA.

In November 2019, Douglas County deputies went to north-central Florida and followed Clanton for days, waiting for him to unsuspectingly leave his DNA on something. They finally got their chance when he went to a bar not far from his home outside Lake Butler, 30 miles north of Gainesville.

Clanton ordered a beer, poured it into a mug and drank. Then he did it again. After he left the bar, detectives grabbed that mug and brought it back to Colorado for testing at CBI.

It was a match.

'We do have a warrant' A carefully orchestrated plan results in killer's arrest

A few minutes before 2 o’clock in the afternoon on Dec. 11, 2019, Douglas County sheriffs Sgt. Attila Denes and Det. Mike Trindle stood along a quiet road outside Lake Butler, Florida, waiting for Jim Clanton.

He rumbled up in his big rig and got out.

“Your name came up initially as a suspect in a major securities fraud case out of Colorado – we’re talking a multi-million-dollar case,” Denes told him. “We started digging into the case. What we actually think happened is someone has assumed your identity back in Colorado.”

Denes asked Clanton to come in for a recorded interview so “we can get your side of what’s going on, make sure you’re not involved.”

Clanton agreed.

None of it is true. Instead, it was a carefully planned cover story aimed at getting Clanton to lock himself into specific details — where he was living when Helene was killed, what kind of car he drove, whether he had a girlfriend.

Their aim: to get him on the record with facts they knew to be true so that he couldn't later claim, for instance, that he’d had a fling with Helene but had nothing to do with killing her.

Once in a small office at the Union County Sheriff’s Office in Lake Butler, Denes and Trindle questioned him for an hour. It all seemed innocuous enough.

Finally, Trindle got to the point.

“You can probably tell by now that there’s more to this than this financial case, right?” he said. “I don't really care about stolen cars in 1980 in Colorado. But we do care about a young woman in Colorado in 1980, and I wanna, um, I wanna show you a picture and see if you recognize her."

Trindle pulled a photo of Helene from his notebook and slid it across the table.

“No, sir,” Clanton responded. “I think I want an attorney now. You accusing me of something else, I know.”

“I do have to advise you of a couple things,” Denes said.

“I’m under arrest?” Clanton asked.

“We do have a warrant for your arrest, for first-degree murder and kidnapping,” Denes said.

“For what?”

“First-degree murder and kidnapping,” Denes said.

“You got the wrong guy,” Clanton protested.

“We actually have your DNA in her, and on her,” Denes replied.

Then a Florida officer handcuffed Clanton and led him to jail.

'I did it' James Clanton admits to killing Helene

At his court appearance the next day, Clanton waived extradition, agreeing to fly back to Colorado to face charges. It was something of a surprise.

But the biggest surprise came as he rode to the airport with Barrella. Clanton said he wanted to talk. Barrella got out his phone and began recording as he read Clanton his rights. Then he started asking questions.

Video below: Audio of Clanton's chilling confession to Helene's murder while riding to the airport.

“OK,” Barrella said. “So, when we contacted you the other day and we were interviewing you about, uh, your time in Colorado, did you have an idea of what we were talking to you about?”

“Yes,” Clanton replied.

“OK. And what did you think that was about?”

“About murder,” Clanton said.

“OK. Why, why did you think we were talking about murder? Did anybody – did either of the cops mention the word murder to you or, um?”

“No,” Clanton said faintly.

“No,” Barrella replied. “OK. So why did you think was about murder?”

“‘Cause, I knew that was gonna come up and get me one day,” Clanton said.

“Why, why was it going to come up and get you – did you murder someone?”

“‘Cause I did it,” Clanton said.

“OK, you did what?” Barrella asked.

“I killed the girl they’re accusing me of killing,” Clanton said.

And there it was – a month shy of 40 years since a man grabbed Helene Pruszynski off an Englewood street, sexually assaulted her, walked her out into a field and stabbed her in the back nine times – a confession.

Clanton kept talking – in the car, during the flight back to Colorado. While on a drive with Douglas County investigators, he answered investigators’ questions about the attack on Helene.

How he approached her after she got off the bus.

“I told her I had a knife,” Clanton said. “She says, ‘I see it,’ and I said, ‘Well, let’s go.’ And she said, ‘OK, I’ll go.’ She wasn’t gonna fight.

“I just opened the passenger door, told her to get in the floorboard. I went around and got in the car and took whatever it was I used to tie her hands up and went that way somewhere.”

What he told her while driving to a wood shed where he would rape her.

“She asked me what I was doing, and I told her I was kidnapping her for money,” Clanton said. “And she said, ‘Well, my parents don’t have any money,’ and stuff like that. I didn’t tell her what I was really doing until we got into that woodshed.”

What he did after pulling to the side of Daniels Park Road.

“We got out of the vehicle, and walked through the field – crossed the fence and walked in through the field,” he said. “And … I told her to get down on her knees and said, I said, ‘You gonna have to walk home from here. So don’t get up until after I leave.’”

After a pause, Clanton continued.

“And, as has happened with me on several occasions, for some reason or another,” he said, pausing before continuing, “I just kind of step out of myself and watch myself do that.”

By “that,” he meant plunging a knife into Helene’s back nine times.

He spoke of a disjointed childhood – being abandoned by his mother, spending time in foster home with a pedophile. And he spoke of a rage inside him he never understood.

“When I was 8 years old, I started with insects, and putting them in red ant piles,” he said, “and went up to amphibians and other small animals. And when I was 8 years old, I hung a cat in a tree and beat it to death with a tree limb. Couldn’t understand why a kid that old could get that kind of rage. That rage has always stayed with me, I mean, it’s – I think every time something hurts me that bad that I can’t deal with it, I learned anger covers up pain. That’s pretty much the basis of everything I’ve ever done. I’m just mad all the time.”

Videos below: Raw body-worn camera footage of James Clanton's confession while on the plane flying to Colorado.

In late February, after prosecutors agreed to take the death penalty off the table, Clanton stepped into Judge Theresa Slade’s courtroom in Castle Rock and pleaded guilty.

'The sunshine of our lives' 40 years later, family & friends get justice

On July 1, Clanton was finally back in front of District Judge Theresa Slade, virtually at least. The hearing had been delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic, and Clanton appeared over video from the Douglas County Jail.

Everyone knew the outcome before it happened: By pleading guilty, Clanton had agreed to a life sentence.

But a sentencing hearing is about more that announcing how long a defendant will be behind bars. It’s about giving him – and the victims – a chance to have their voices heard.

Clanton passed, letting his attorney issue an apology on his behalf.

But more than a dozen people who loved Helene didn’t let the opportunity go.

Forty years is a long time. But it wasn’t long enough to dull the pain for those close to Helene – or their cherished memories of her.

“We idolized her,” her sister, Janet Pruszynski Johnson, told Judge Slade. “She was the sunshine of our lives. We adored her and came to realize she was a special light in our family and in the world around her.

“We knew Helene was going places. Her warm personality, friendly nature and strong convictions gave us pride in all she did. We knew she was destined for great things in the future.”

That was a future that ended on the cold ground along Daniels Park Road.

“Everything was taken from her on Jan. 16, 1980,” said a college friend, Monique Shire. “She was deprived of what she would have accomplished. The world was deprived of what she would have contributed to make it a better place. Her family and friends were deprived of sharing with her all that life had to offer.

“For me, the brutal act of taking her life is unforgivable. The terror and pain that she experienced haunts me every day. I have learned to live with my sorrow and anger, but will never be able to reconcile how such a horrible thing could have happened to such a wonderful person.”

“After Helene’s death, I had bad dreams for a long time,” said her high school boyfriend, Jonathan Shailor. “I would see her in her casket, her eyes struggling to open. And then I would wake up and have to relive the shock of remembering she was gone. I dreamt that I was at the kitchen table with her parents, we were grieving together, and then they’d tell me that she had somehow survived that brutality, that she was in her bedroom down the hall. But I was not permitted to see her, no one was.

“Eventually the bad dreams ended, and only the aching loss remained. I still think of Helene every day.”

And then he played a slideshow of photos of Helene, covered with a recording of her college a capella group, the Wheatones, singing, Helene’s voice mingling with the others, the final words a fitting description for those who knew her and cared for her as they emerged from 40 years in the dark.

There's a light in the depths

Of your darkness.

There's a calm at the eye

Of every storm.

There's a light in the depths

Of your darkness.

Let it shine

Oh, let it shine.

Contact 9Wants to Know investigator Kevin Vaughan with tips about this or any story: kevin.vaughan@9news.com or 303-871-1862.

Editor’s note: This story is based on reports from the Englewood police department, the Douglas County Sheriff’s Department, the Colorado Bureau of Investigation, and the Douglas County Coroner's Office; crime scene photographs; family photographs provided by Janet Pruszynski Johnson; 1980 news reports from 9NEWS, the Rocky Mountain News, The Denver Post, the Associated Press, and the Castle Rock News-Press; press releases issued in 1980 by the Douglas County Sheriff's Office and KHOW radio; audio recordings of interviews with Jim Clanton and other witnesses conducted by Douglas County sheriff’s investigators; body camera footage of Douglas County sheriff’s investigators interacting with Clanton; court documents, including the arrest affidavit for Clanton; statements made at Clanton’s court appearances, including his sentencing hearing; information provided by Kitsey Snow; and interviews with Janet Pruszynski Johnson, Douglas County sheriff’s Lt. Tommy Barrella, Douglas County sheriff’s Sgt. Attila Denes, and Douglas County sheriff’s Detective Shannon Jensen.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Investigations from 9Wants to Know