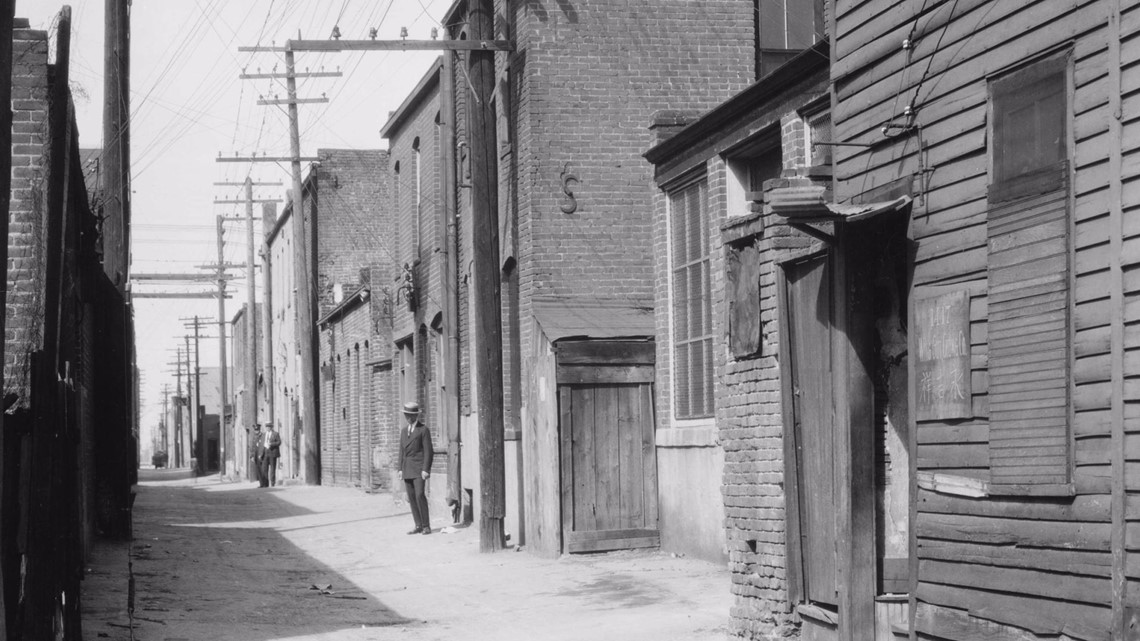

DENVER — Denver's lower downtown, known today as LoDo, with a major league ballpark, bars and apartments, was once where this city's Chinatown existed.

According to History Colorado, Denver's Chinese population was scant prior to 1870, but immigrants looking for railroad and mining jobs came to Denver to earn a living.

“At that time, Chinatown was essentially a working-class community,” said Dr. William Wei, former Colorado State Historian and author of "Asians in Colorado."

“There were many Chinese who were working in the mining industry,” Wei said. “Like other miners, they would come to Denver for rest and recreation.”

About 500 Chinese people lived in Denver's Chinatown at its peak, according to Wei. They lived in the heart of the city because of its centralized location.

> Video below: Re-envisioning Denver's historic Chinatown, aired Aug. 8, 2021:

Not everyone in Colorado favored the addition of a Chinatown.

Chinese immigrants were reliable and worked hard, often for lower wages than other immigrant populations, Wei said. This led to competition for work.

“There was the Chinese question – the issue of the importation of Chinese labor viewed as unfair competitors by white workers and the demand to exclude them from the country,” he said.

Chinatown also gained a reputation for its opium dens and was called Hop Alley.

In 1880, the United States was set to elect a president. Republican James Garfield squared off with Democrat Winfield Hancock.

“Hancock accused Garfield of importing cheap Chinese labor,” Wei said.

The issue hit home for many residents of the American West, including in Colorado. On Oct. 30, 1880, Garfield’s opposition held an anti-Chinese parade in Denver.

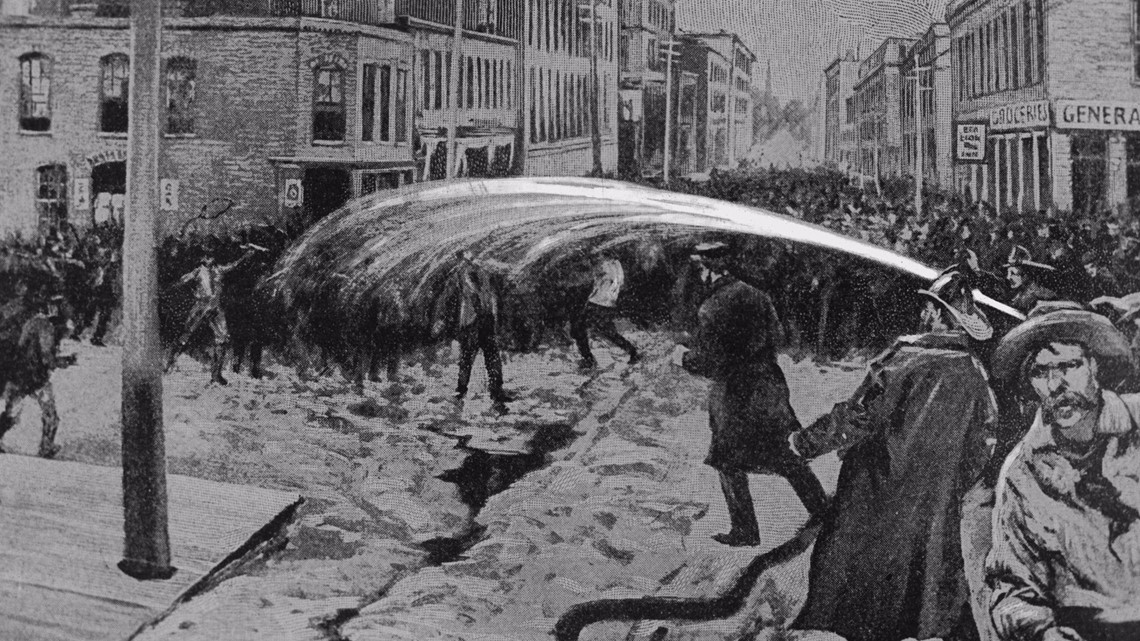

Tensions came to a head the next day. Around 2 p.m. Oct. 31, two white men drunkenly stumbled into a Wazee Street saloon.

“One of the drunken individuals struck one of the Chinese, initiating the riot,” Wei said. “That attracted 3,000 to 5,000 Denverites to descend upon Chinatown.”

The small Denver police force couldn’t manage the mob. The fire department tried to assist by spraying the mob with fire hoses, but that only enraged them more.

Hundreds of Chinese were arrested in the riot. Police told them it was for their own protection.

One man, Sing Lee, was killed. The mob brutally beat him and hanged him from a lamppost.

“It’s surprising that only one person was killed, but I have to say it wasn’t for lack of trying,” Wei said. “They were intent on killing as many Chinese as they could.”

Some media portrayed the Chinese as instigators of the event.

“The Rocky Mountain News was anti-Chinese,” Wei said. “As far as they were concerned, this was justified, and their portrayal tended to blame the Chinese for it rather than the unprovoked attack against the Chinese.”

According to History Colorado, Chinatown business owners and residents lost more than $53,000 worth of property.

> Video below: Denver apologizes for its role in the anti-Chinese riot of 1880, aired April 16, 2022:

Denver’s first race riot was that day. It was just one of more than 200 across the American West around that time.

It led to the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which prohibited the immigration of Chinese laborers.

“This was very significant in U.S. history because it was the first such act that singled out a group of people for exclusion,” Wei said. “It also signaled the end of free immigration to the United States. Ever since then our immigration policy has been a restricted one.”

This act was fully retracted with the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. In 2011 and 2012, the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives respectively passed resolutions officially condemning the Chinese Exclusion Act.

“As a democracy, we should be willing to come to terms with the truth and to try to rectify injustices of this sort. An apology is great,” said Wei, with a sarcastic laugh. “2011 [was] a long time coming, but nevertheless, it’s a recognition of a mistake.”

Wei said looking at events that happened nearly 130 years ago helps us recognize the cyclical nature of life.

“I think hindsight really is foresight," he said. "To view immigration as objectively as possible rather than to be influenced by a lot of the political rhetoric that surrounds us.”

This story was originally published Oct. 31, 2019.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Full Episodes of Next with Kyle Clark