DENVER — Women have been allowed to serve in the U.S. Armed Forces since 1948.

In the more than 75 years since, thousands of women have stepped up to serve their country.

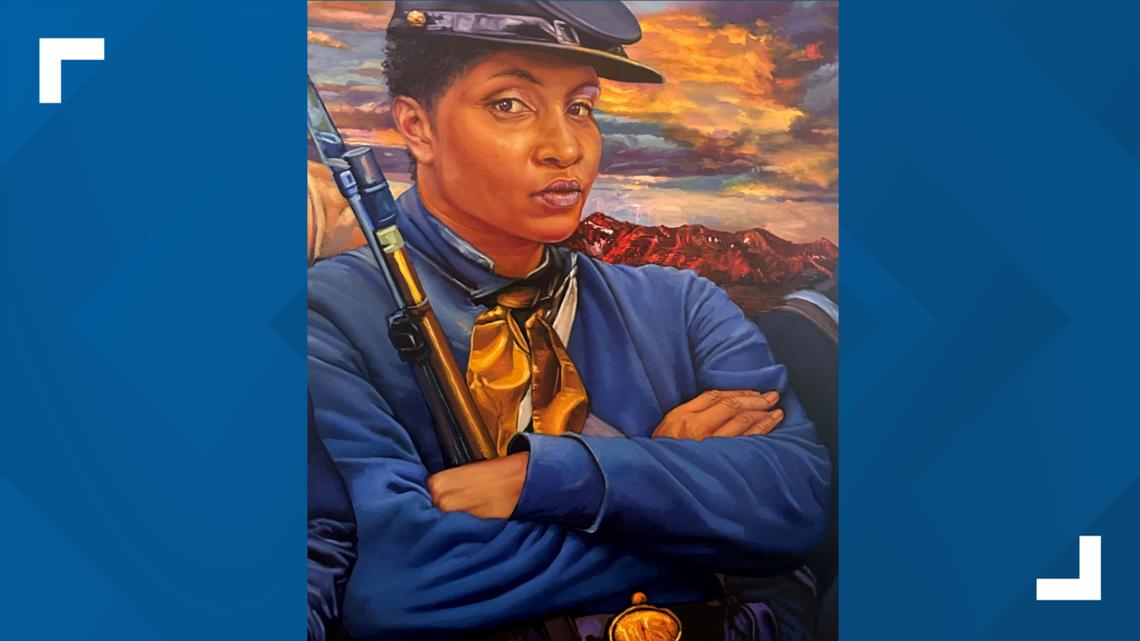

But back in the 1860s, soon after the Civil War, a free Black woman named Cathay Williams came forward to serve her country, too.

“Cathay Williams. She was the first Black woman to enlist in the U.S. Army and also the only documented female to serve with the Buffalo Soldiers,” said Acoma Gaither, Assistant Curator of Black History at History Colorado.

Williams was born in 1844 in Independence, Missouri.

“Her father was a free man and her mother was enslaved which meant her status was also enslaved. And she worked on a plantation in Missouri,” Gaither said.

In the early 1860s, the Union Army came into Jefferson City, where the plantation was located, and the Army occupied the area.

“And any captured enslaved person was then assigned to be contraband for the U.S. military,” Gaither said. “ When you’re contraband, you’re basically made to serve the Army in various roles such as in food, as a cook or as an aide, as a nurse or in laundry. And Cathay actually did all three of those things.”

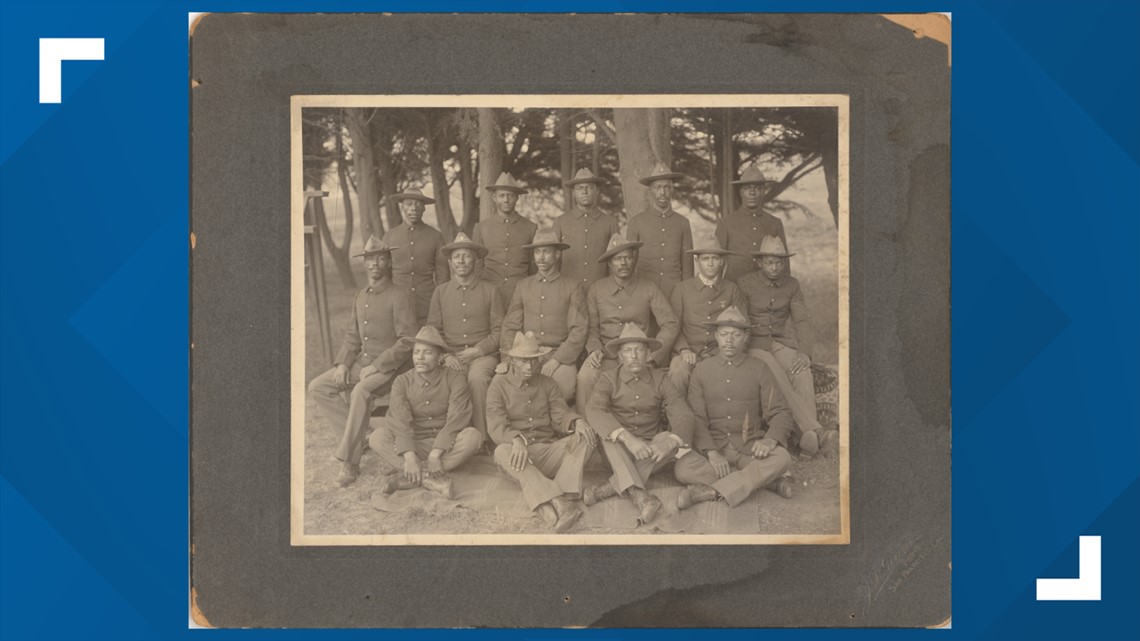

After the Civil War ended, Congress signed off on the creation of an all-Black military unit.

“And Cathay actually signed up for one of them. And she did so for a few reasons, one was she wanted to be financially independent, that was very important to her,” Gaither said.

“She actually enlisted as a man,” Gaither said. “She went under the pseudonym of William Cathay, so she flipped her names. And she enlisted with the help of her cousin and one of her friends into the U.S. military. She cut her hair and put on a uniform because at that time, being a woman in the military was illegal.”

Williams was now a part of the 38th Infantry of the Buffalo Soldiers, assigned to the New Mexico territory and moving out to the area soon after, Gaither said.

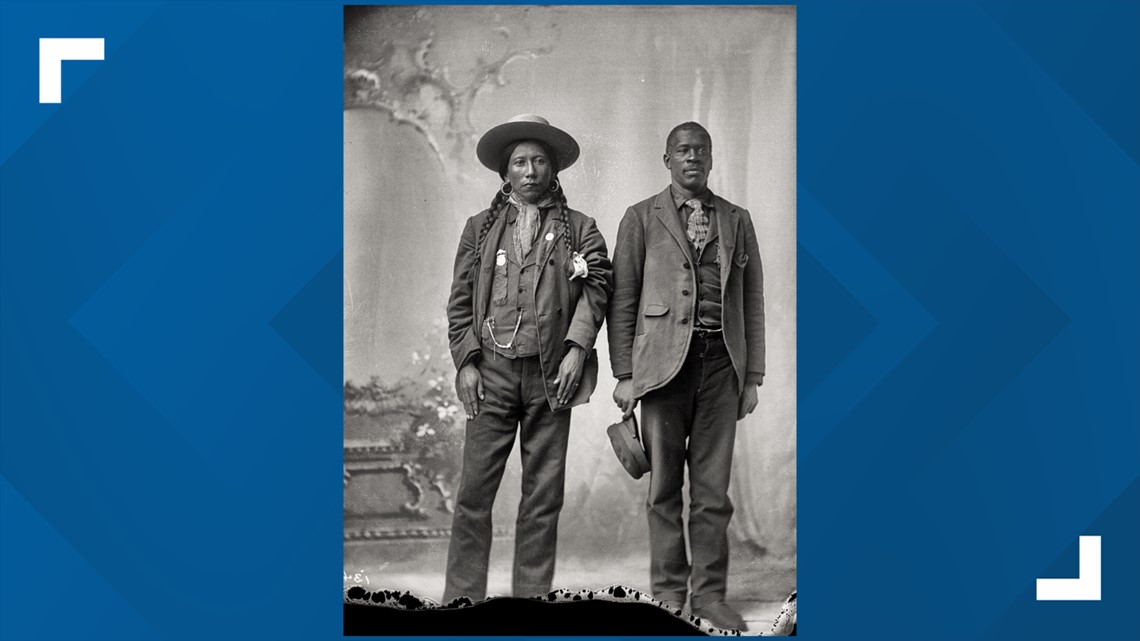

“They were an all-Black military unit. At this time, they were really helping with westward expansion. They served along the railroad and they were also used by the federal government in removal of Native American communities in the southwest,” Gaither said.

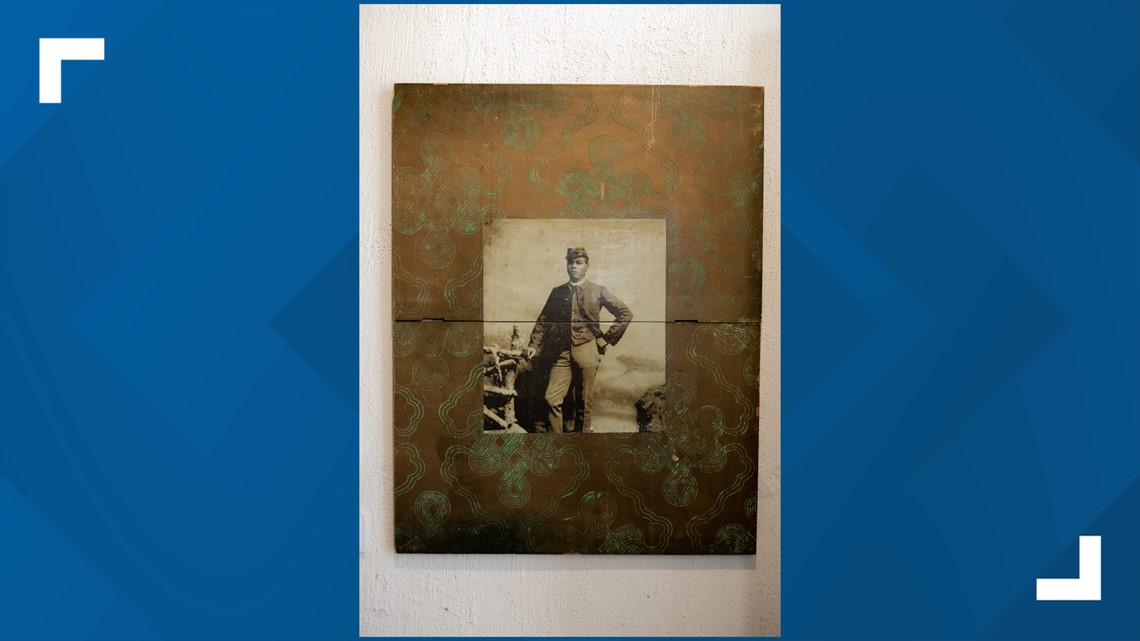

Williams is the only documented Black woman that is confirmed to have served in the military during that time. And she served for almost three years.

“There was a point where she had to swim across the Rio Grande River and she got frostbite because they were marching in the wintertime and they weren’t properly clothed. So she actually got frostbite on her toes and they had to amputate her toes,” Gaither said. “There was a bunch of instances where she was hospitalized. She got smallpox twice, too. Yes. And I will note that every time she went into the hospital, she was able to conceal her identity as a woman.”

Following the series of hospitalizations, Williams recognized the toll military service had taken on her body, Gaither said.

“So she decided to go see the doctor that had seen her numerous times in the past and she actually outed herself. She said that she was a woman and then she was honorably discharged from the Army at that time,” Gaither said.

In the years that followed, Williams moved to Pueblo, Colorado, opened a laundry business and got married. But, soon after that Williams’ husband stole from her and she had him arrested.

She relocated again, this time to Trinidad, Colorado.

“When she was living in Trinidad, she applied for disability pension during her service for the Buffalo Soldiers,” Gaither said. “She applied three different times and she was denied every single time. And I believe that was due to discrimination.”

But Williams was also recognized for her service by some.

“There was a reporter from the St. Louis Times that came down to interview her because he was doing a story on men who served in the military and people in Trinidad were like ‘Hey, we know Catie Williams, she was a part of the Buffalo Soldiers, you should definitely talk to her,’” Gaither said. “That is actually one of the only documents that we know of her retelling her story.”

Williams’ record on the census disappears in the early 1890s. But, according to Gaither, a researcher at Pueblo Library has found documentation of a patient being admitted to a hospital under the name Catherine Williams, later scratched out to say William Cathay. The patient, like Williams, had amputated toes.

Historians now believe Cathay died in 1911 and was buried in a Pueblo cemetery, Gaither said, but exactly where remains a mystery.

“I think her story is so remarkable during this time because there’s not a lot of stories of early Black women serving as a soldier during this time period. And it really shows her independence and strength at that time,” Gaither said. “She had a drive for wanting more independence in her life. And to conceal your identity for three years I think is also remarkable.”

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Colorado’s Leading Ladies