DENVER — A run around Berkeley Lake with sisters Sam Monson and Libby Seamans will only prove two things: cystic fibrosis has nothing on their positive attitude or average mile time.

Monson and Seamans have both been diagnosed with cystic fibrosis, a chronic and genetic disease that often damages the lungs and other organs.

"When we were born, the life expectancy was in the teen years, and through therapies that have been developed, our life expectancy is now in the 50s," Monson said. "Our personal life expectancies are expected to be much greater than that based on the excellent care that we received."

Monson and Seamans were born three years apart, but both being diagnosed with cystic fibrosis brought them closer in a way they would never wish upon the other.

"Obviously I’ve only ever known CF as having a partner in Libby with it. While I wish Libby didn’t have it, I also can’t imagine coping with the disease without her," Monson said.

"It's made our sisterhood and our friendship so much stronger to have that shared experience," Seamans said.

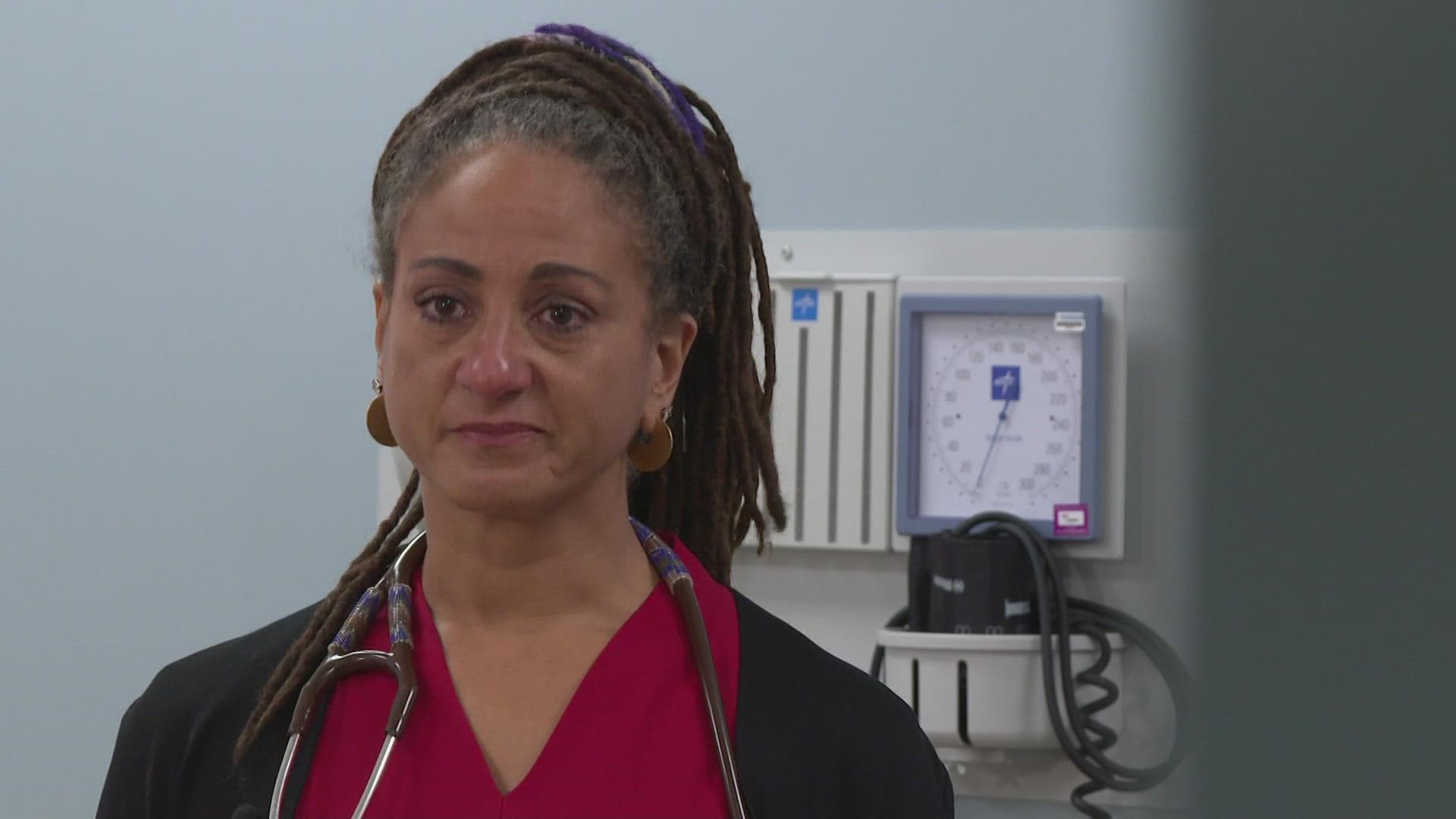

Shared experience led them both to National Jewish Health's cystic fibrosis center, led by Dr. Jennifer Taylor-Cousar.

"So up until 2012, all of the drugs that we used to treat CF were for the signs and symptoms," Taylor-Cousar said.

"More recently I was involved as a principal investigator and on the steering committee to develop the clinical trials to develop a drug called Trikafta, and because it works on the most common mutation, that covers about 90% of people with cystic fibrosis," she said.

Taylor-Cousar said life expectancy for those with CF has gone up from less than 30 years, to 53 years, thanks to new medications like Trikafta.

"Even for people like Sam and Libby, when they were born the average life expectancy was still less than 30 years of age," she said.

"Medications like this will make it possible for Sam and Libby to actually see their kids get married and see their grandchildren," she said.

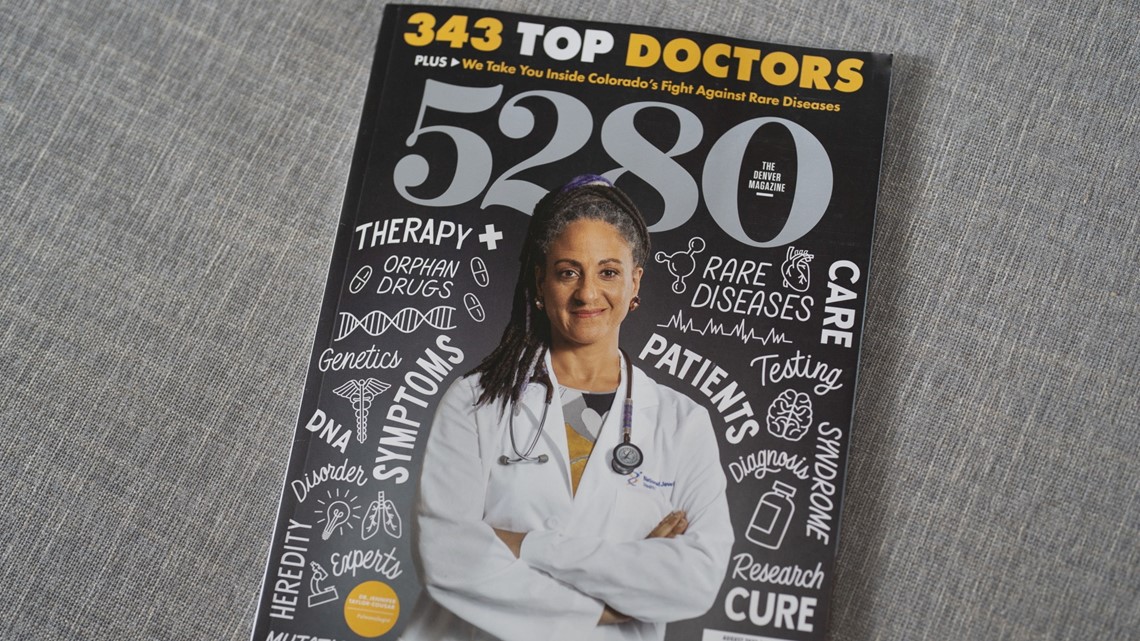

Taylor-Cousar was recently honored on the cover of 5280 magazine as a top doctor for her work in the CF field. She told 9NEWS she hopes it encourages other women of color to follow their dreams.

"It’s not just the honor itself but hoping I’m going to inspire some young woman or some young kids of color that they can also be physicians," she said as she held back tears. "And get seats at the table to make critical decisions."

Taylor-Cousar's work is not over. The next step is gene therapy. She is holding a trial at National Jewish Health for a study that will help all mutations of cystic fibrosis.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Latest from 9NEWS