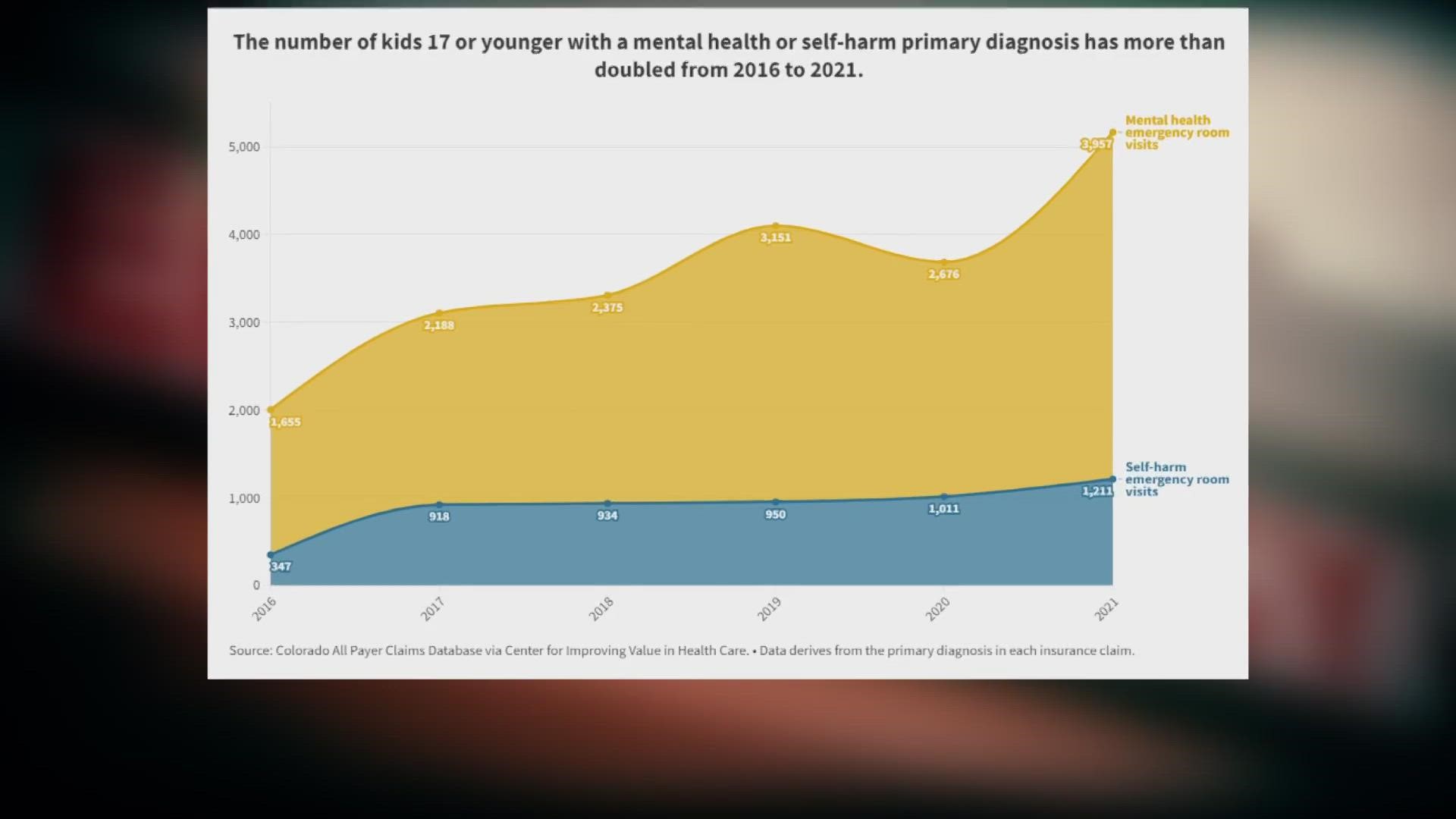

COLORADO, USA — The number of kids in emergency rooms with a mental health or self-harm primary diagnosis has more than doubled from 2,002 in 2016 to 5,168 in 2021, according to a review of data compiled by the Center for Improving Value in Health Care.

CIVHC analyzed data pulled from health insurance claims to the Colorado All Payer Claims Database.

Dr. Chris Rogers, psychiatrist and medical director at HealthONE Behavioral Health and Wellness Center, said the phenomenon is not new to him and his team. The data shows the mental health care system is “outgunned and outmanned.”

“It means that kids are struggling,” he said. “It means that our healthcare system is being reactive, because by the time you’re in the emergency room or you’ve hurt yourself, in my mind we’ve already sort of failed you as a youth.”

Rogers said the children he treats often lack identity or don't see a clear meaning to life.

“I can’t tell you how common it is to have a 14-year-old with a nihilistic existential crisis of ‘what’s the point of any life, we’re going to die?’” he said.

Across six years of data, two in five visits to the ER across all age ranges for a mental health disorder were for anxiety. Major depressive disorder and panic disorder were the other common ailments.

Age-specific data on diagnosis was not available.

Dr. Karen Woolf, Pediatric Emergency Physician and Medical Director at Rocky Mountain Hospital for Children, said she has seen an increase in the number of kids in the emergency room for mental health treatment. She said youth patients typically report hopelessness, suicidal thoughts and anxiety. And there are often kids who come back multiple times.

Woolf said it can be frustrating because they are more prepared to handle physical injuries, not mental crises.

“We are very well equipped to manage that, and we are in fact experts in managing that,” she said. “We are not experts in managing ongoing mental health issues. It becomes hard because we know we’re not giving the best care for these kids while we’re waiting for definitive care.”

Woolf said seeing her patients dealing with mental health problems is hard to see.

“It’s definitely heartbreaking. As a mom of teenagers, for me it feels a little personal, because you worry about what’s going on to create these conditions that mine and other folks’ kids are living through,” she said.

Self-harm is even more prevalent among kids, too. The number of self-harm emergency room visits for kids has more than tripled from 347 in 2016 to 1,211 in 2021.

“Not to minimize the dangers involved there, because it can become very dangerous, but there is this sense of this as a normal coping mechanism, that teenagers seem to share among each other as this is the plan to help themselves feel better," Woolf said.

The data shows admissions are falling. There were 23% fewer admissions for those with a mental health diagnosis, from 1,895 admissions in 2016 to 1,464 admissions in 2021. There is no age breakdown of admissions, so it is not clear how many of those were adolescent admissions.

“Once it becomes an issue of waiting for kids to find a mental health inpatient bed, and that’s what they need, we’re not equipped to take care of that kid until that bed is found,” Woolf said. “We can basically keep kids safe and hope it’s a short wait.”

Rogers said solutions include opening up children’s worldviews to different types of what “success” looks like. It is not just one path to a fulfilling life.

“A lot of kids are just then put in a position of, if they don’t feel like they are on that track to get good grades and get into a really good school, then before they’ve even reached the starting line of life, they feel like they’ve already failed,” he said.

Rogers said social media use provides an opportunity for kids to compare themselves not just with their classmates but with the world, and that they feel like they are not measuring up. Rogers said parents should focus on the small successes in their kids’ lives.

“[Find] small successes and things that give them joy,” he said. “And saying that is enough and that life is about things that aren’t necessarily worth posting on Instagram. And that having straight A’s maybe isn’t the path to happiness.”

Rogers recommended adding more resources to mental health treatment options in schools to help meet more kids where they are and adding a variety of treatment plans to include outpatient treatment choices. Woolf said another possible help would be expanding the number of adolescent and pediatric mental health treatment beds.

In September, HealthONE opened a behavioral health and wellness outpatient service center in Aurora. The program provides an intermediate level of care for youth ages 9 to 17 who have needs too complex for individual therapy alone, but who do not require inpatient care.

Robbie's Hope, a Colorado nonprofit with the goal of preventing youth suicide, has a series of handbooks written by teens for adults to help parents talk to their kids about anxiety, depression and suicide.

You can download the handbook for free on their website.

Resources for teens:

Check out more resources on the Robbie's Hope website.

Reach investigative reporter Zack Newman at 303-548-9044. You can also call or text securely on Signal through that same number. Email: zack.newman@9news.com. Call or text is preferred over email.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Mental Health & Wellness