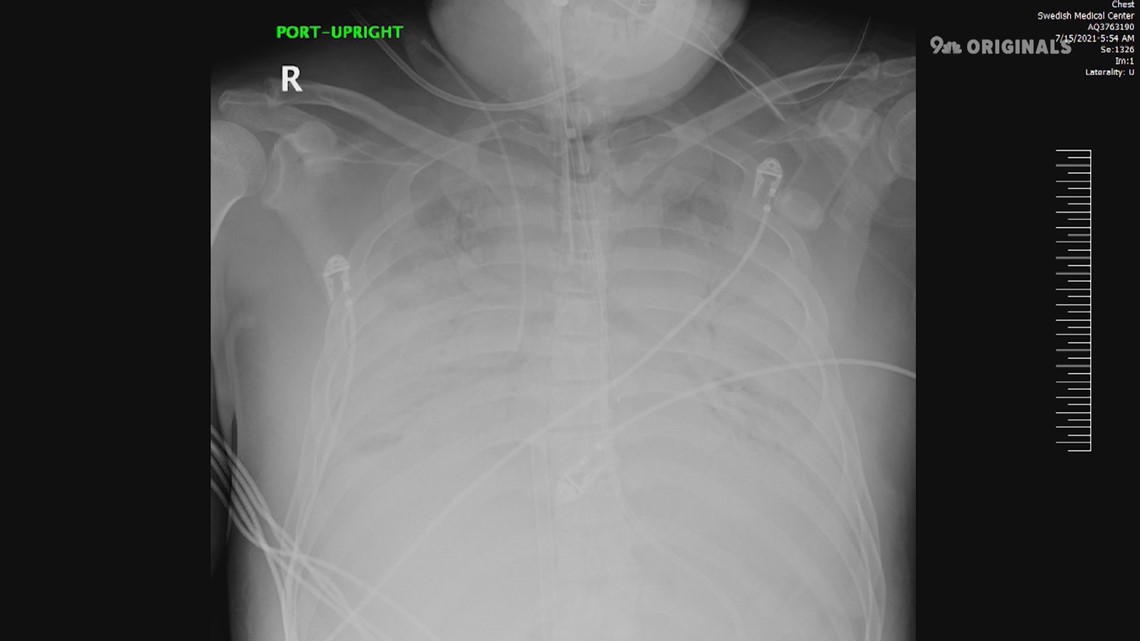

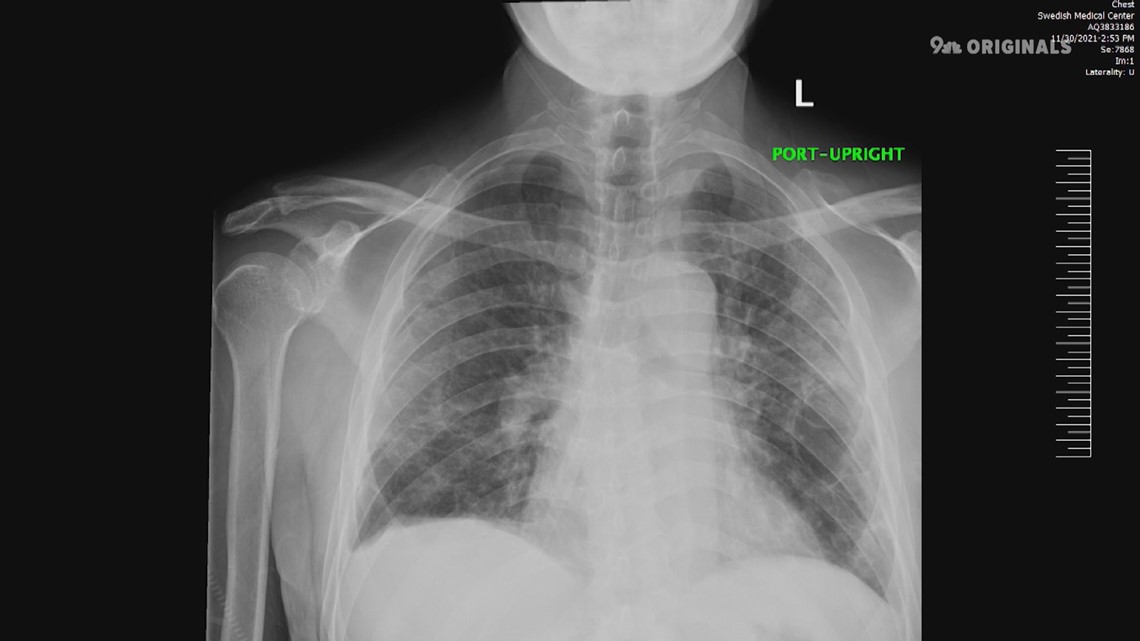

ENGLEWOOD, Colo. — The doubt crept back in around week eight. Under an X-ray, the lungs remained white. No air in the lungs. Just infection.

Everywhere.

COVID had done its worst.

It was around this time that Swedish Medical Center’s Dr. Luciano Lemos-Filho decided he really needed some outside help. He called other doctors around the country.

They told him he needed to remain patient.

“They told me, 'Just keep going. Stick with it,'" he said.

A week or so later, the X-rays started to show a change. After more than two months on a machine known as an ECMO, the patient’s lungs were starting to heal.

Where once there was white – all white – there were suddenly patches of black.

Air.

“It’s a miracle. It’s a scientific miracle happening in front of your eyes. It’s really amazing,” Lemos-Filho said.

ECMO is short for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. It involves pumping blood out of the body, oxygenating it within the machine, and then sending it back into the body.

Doctors have used ECMO for decades to help treat critically ill patients, but in the early days of COVID, few were certain it would play a large role in treating patients during the pandemic.

Doctors would use ECMO for a few days to a week or so, at most, typically.

“Not months and months. This was not something we did,” Lemos-Filho said.

At first, he wasn’t even sure Swedish would have the staff to support such an effort. ECMO requires two nurses to be present at all times. At a time when COVID patients were flooding into hospitals around the region, it was hardly a given the hospital – or any hospital for that matter – would have the resources to keep it up and running.

Something had to give.

Ventilators worked well to assist COVID patients with severely diminished lung capacity, but even vents weren’t enough to save the lives of people with massive lung infection.

When vents failed, ECMO provided an option.

Considering half of all patients on ECMO will still die, it’s not exactly a great option, but it’s an option nonetheless.

And, beyond ECMO, there are no other options for those patients.

“This is a Hail Mary,” Lemos-Filho said.

The ECMO team

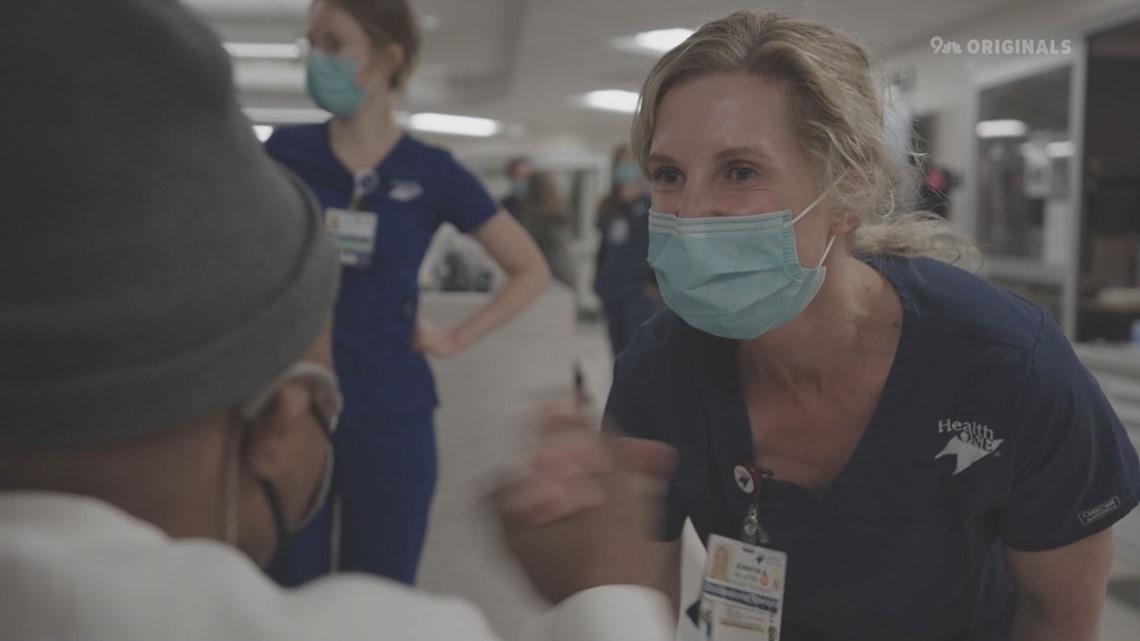

Charay Bourne, RN, is part of the ECMO team at Swedish. Early on, the team learned it would be best to get the patient on ECMO inside the ICU room as opposed to moving the patient somewhere else.

“We bring everything over. We’ve got an ECMO bedside cart. We pick out the cannulas beforehand. We set up the pump,” she said.

It must be done quickly, too.

With failing lungs, the patients don’t often have more than an hour or so.

“From start to finish, I think our quickest time was 12 minutes,” she said.

Lemos-Filho said the first patient on ECMO at Swedish died one and a half months in. It was a tough day for the team.

“Sometimes you’ll see patients getting better, getting better over a couple of days, and then all of a sudden they go downhill very quickly,” Dr. Chirag Chauhan said. “The hardest part is just that we don’t know which patients are going to do that and which ones aren’t.”

Thankfully, there were big success stories as well.

Consistent with the national average, 50% of the ECMO patients at Swedish survived.

One of those who survived was Nate McWilliams, who spent three months on ECMO and 158 days in the hospital.

Earlier this year, he returned to the very ICU staffed by the same people who saved his life.

“I still can’t believe it,” he said. “Everybody stood by my side.”

Sara Lombardo, RN, is the director of the cardiac ICU and was one of the many who watched McWilliams' recovery by his side.

“It was part of the learning process for everybody of giving that opportunity for the lungs to have time to heal and recover,” she said.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: COVID-19 Coronavirus