EVANS, Colorado — We know it’s happening all the time: someone takes a drug, overdoses and gets a second chance.

But even with millions of dollars spent on naloxone in a year, most Colorado police departments don't keep track of how often they're using it -- making it a challenge to properly distribute resources.

"The number of overdoses are staggering right now," Evans Police Chief Rick Brandt said. "We’re very responsive right now. We’re not as proactive as I think we need to be."

Brandt’s office at the Evans Police Department is full of second chances. Boxes are packed with naloxone, or Narcan as it's commonly known. His officers give the lifesaving drug to anyone who wants it.

> Watch: Evans Police use two Narcan doses to reverse the effects of drugs a man had taken

He’s the reason hundreds of law enforcement officers in Colorado now carry naloxone everywhere. He first started telling departments about the overdose-reversing drug years ago.

"Today I think I’ve been involved in training 220 agencies," Brandt said.

But even the chief who’s led the push for naloxone can’t tell us how many lives his officers have saved.

"I’ve been asked repeatedly over the years, 'hey, can you give us data? Can you give us data?'" Brandt said. "The answer is I wish. I can’t right now."

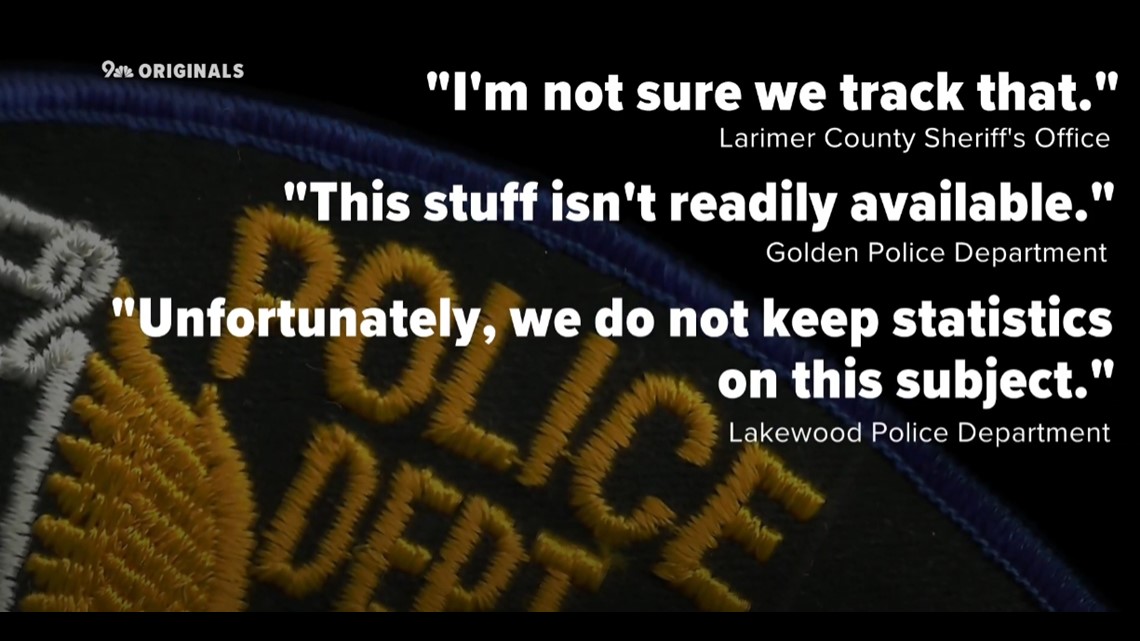

9NEWS asked for that data, from dozens of agencies across the state.

“This stuff isn't readily available,” Golden Police told us.

“I'm not sure we track that,” we heard from the Larimer County Sheriff’s Office.

“Unfortunately we do not keep statistics on this subject,” Lakewood Police responded.

Brandt knows that’s a problem.

"Right now we’re just reacting," he said. "There’s no way to really track it. There’s not a code that we can put in our computer and say, 'hey, I deployed Narcan.'"

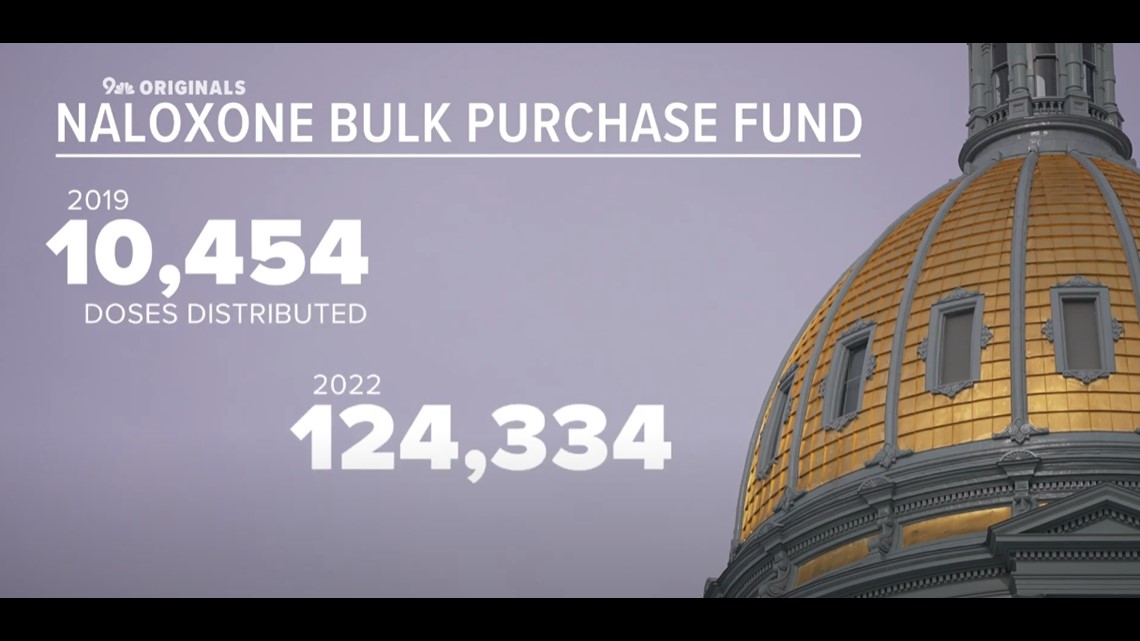

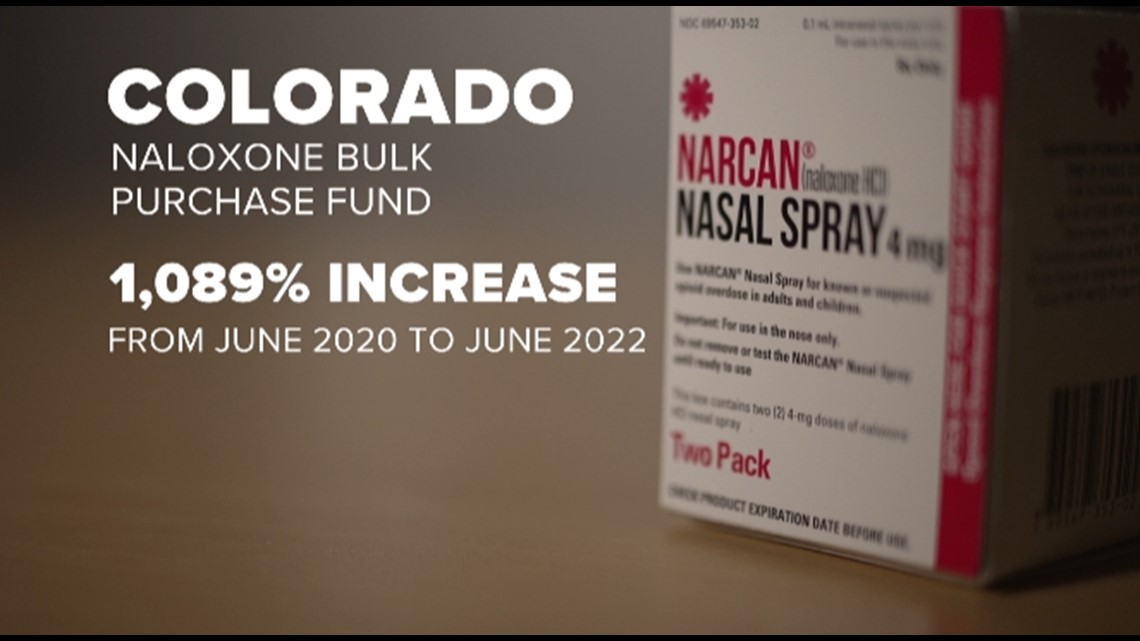

The state buys naloxone for most law enforcement agencies through its bulk purchase fund. In 2019 10,454 doses were distributed. By 2022, that number skyrocketed to 124,334. That’s up more than 1,000% in just two years.

The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment said it spent $4,283,822 to purchase the naloxone for the fiscal year 2021-2022.

Even with millions of dollars spent, no one knows how, or even if, it’s being used.

"It’s a blind spot," said Rob Valuck, Director of the Center for Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention at the University of Colorado School of Pharmacy. "We know a lot about a lot of things, but that piece is an unknown. It’s a blind spot."

Valuck created an app called OpiRescue that gives anyone the ability to keep track of how and where naloxone is used. Some police departments use a similar app called OD Map. But even for the limited number of people and departments that do keep track, it’s hard to know if the numbers are accurate.

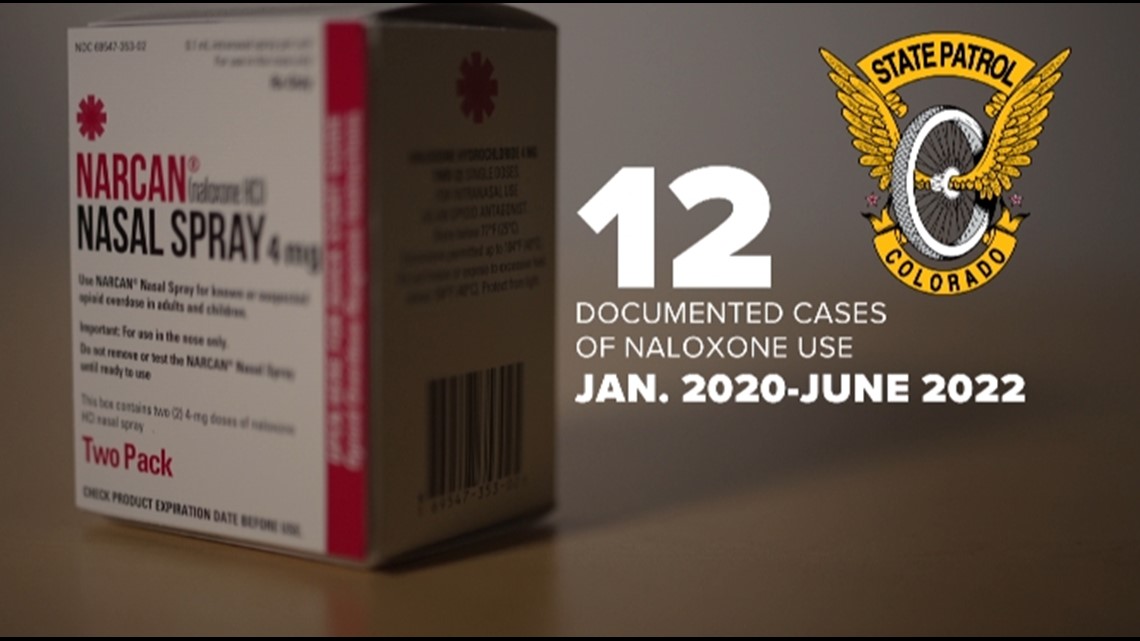

Take Colorado State Patrol, for example. From the beginning of 2020 through June 2022, there are only 12 documented uses of naloxone. That may be true, but even Valuck finds it hard to believe.

"It’s impossible that that’s accurate," Valuck said. "It’s an undercount."

Valuck said there's no incentive for departments to accurately keep track of naloxone use. That means it’s hard to properly distribute resources.

"We’re investing a lot of money as a state and using federal funding to distribute the product, but we’re not keeping up with the data collection part," Valuck said. "If we can get data on where do people use it, where is the need the highest, we can direct more resources there, have more Naloxone available there, and save more lives."

Colorado state Rep. Chris Kennedy helped create the state fund for naloxone. Now he’s considering changing the requirements for keeping track of when it’s used.

"At the time we created the fund, we didn’t talk a lot about requirements on law enforcement agencies," Kennedy said. "We just wanted to push naloxone out and get it out there in the community."

Kennedy said after 9NEWS raised the point, he's researching whether he can add requirements for how the use of naloxone is tracked.

"To be honest, you were the one who sparked the conversation for me reminding me about the importance of this topic," Kennedy said. "Now that this is a part of the conversation, I do think I’m going to initiate conversations with folks and find out whether we want to take action this next year."

So why is it so hard to keep track of naloxone use as the number of doses in Colorado increases dramatically?

Whenever officers respond to an overdose, there’s no code in their computer system telling them it’s an overdose. It’s just a medical call.

From there, it’s up to each department to decide whether they keep track of what type of call it was or if Narcan was deployed.

"I’d like to be more proactive," Brandt said. "Say, 'hey, we’ve gotten two calls or three calls of overdoses in this area in the last week, we’ve probably ought to get some resources in there to see if we can address it before it gets bad.'"

Knowing more could put the right resources in the right places -- stopping the next overdose before second chances run out.

"If we’re having a hot spot somewhere in our community, I’m not going to throw more cops into it trying to intercept more drugs," Brandt said. "I’m going to call our behavioral health partners and harm reduction partners and say, hey, we need to focus here."

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: 9NEWS Originals