ENGLEWOOD- 9NEWS Education Reporter Nelson Garcia and 9NEWS Photojournalist Byron Reed took a look at a variety of universal education issues through the lens of a first-grade classroom in the Englewood School District that they followed for a year.

They asked the simple question: what is school like for the class of 2025?

When it comes to learning, Cerri Norris calls it an evolving process. In Cherrelyn Elementary School and across the Englewood School District, every student from kindergarten to eighth grade was provided an iPad for the school year.

"There's so many apps we can use for reading and writing and math," Norris, a first-grade teacher, said. "I'm really excited."

In September, Norris handed out iPads to her students for the first time. In grades kindergarten through third grade, the iPads stay at school. From fourth through eighth grade, the students can take them home. In the lower grades, the tablets are encased in hard, plastic carrying cases to keep kids from breaking them.

"They're pretty sturdy," Norris said. "They have a screen protector. So, hopefully, it will keep sticky things off of our screens."

On the first day of the iPads, students were enthralled, exploring the different learning programs.

"It is so quiet," Norris said.

Cherrelyn Elementary Principal Eva Pasiewicz believes the iPads can make a big difference in the classroom.

"It stretches their minds to use technology in different ways," Pasiewicz said. "Our students are fortunate in this district. The district really looks out for them and tries to give them what they don't have."

Pasiewicz says the iPads can make a big difference at home, too.

"Our kids come from a lower socio-economic background, and they don't have much access to many books at home," Pasiewicz said. "So, for the students who are able to take their iPads home, it gives them a wide variety of library books to choose from when they're home."

But, apps can be confusing, and programs don't always load.

"We had some issues at the beginning just trying to work out some bugs," Pasiewicz said.

Catching up with the class six weeks later, Norris says things are running much more smoothly. She says the iPads have enhanced her lessons in math and reading. Norris adds that the devices help kids with writing, too, both academically and physically.

"I've actually gotten styluses for each of them to use," Norris said. "When they're writing on their iPads, they can practice pencil grip."

Pasiewicz says the iPads have opened up a new dimension in learning.

"I never thought I'd have the opportunity to work in a building that has an iPad for every student," Pasiewicz said. "It's very exciting, challenges the teachers in different ways, [and] challenges me as a leader to help the teachers."

Still, the iPads do run out of power, and Norris says creating lesson plans can be difficult.

"It's definitely a little bit harder than I expected, trying to integrate them to all of our instruction," Norris said. "There are so many options."

Despite all the warnings, the iPads have hit the ground.

"We have had a few drops already," Norris said. "Luckily, they're in those nice blue cases, and those cases have been working really well."

However, she admits, creating too much screen time can be an issue.

"We break it up quite a bit," Norris said. "So, we try to do iPads, and then we come back to the carpet, read a real book, have real discussion, [and then] back to iPads. You have a brain break, [and then] back to iPads."

Through the course of the year, Norris says she became more efficient with the iPads and the kids became more proficient.

"It's like my favorite thing to do," Evan Rouse, first grader, said. "I like doing stuff about numbers."

Sometimes, the iPads are a distraction, Norris says.

"We had some major behavior issues with the iPads at one point, and so I pulled the iPads for a week," Norris said. "Kids doing things they're not supposed to be doing on the iPads. That's very typical. So, we just needed to figure out how we were going to monitor that, and how we were going to instill that responsibility into students."

At the end of the school year, Norris says the iPad evolution was a success.

"Overall, I think the iPads went really well. The second half of the year, we really got things nailed down," Norris said. "So, I think just after this kind of experimental year, we're really set up for next year."

Englewood started the new year Wednesday.

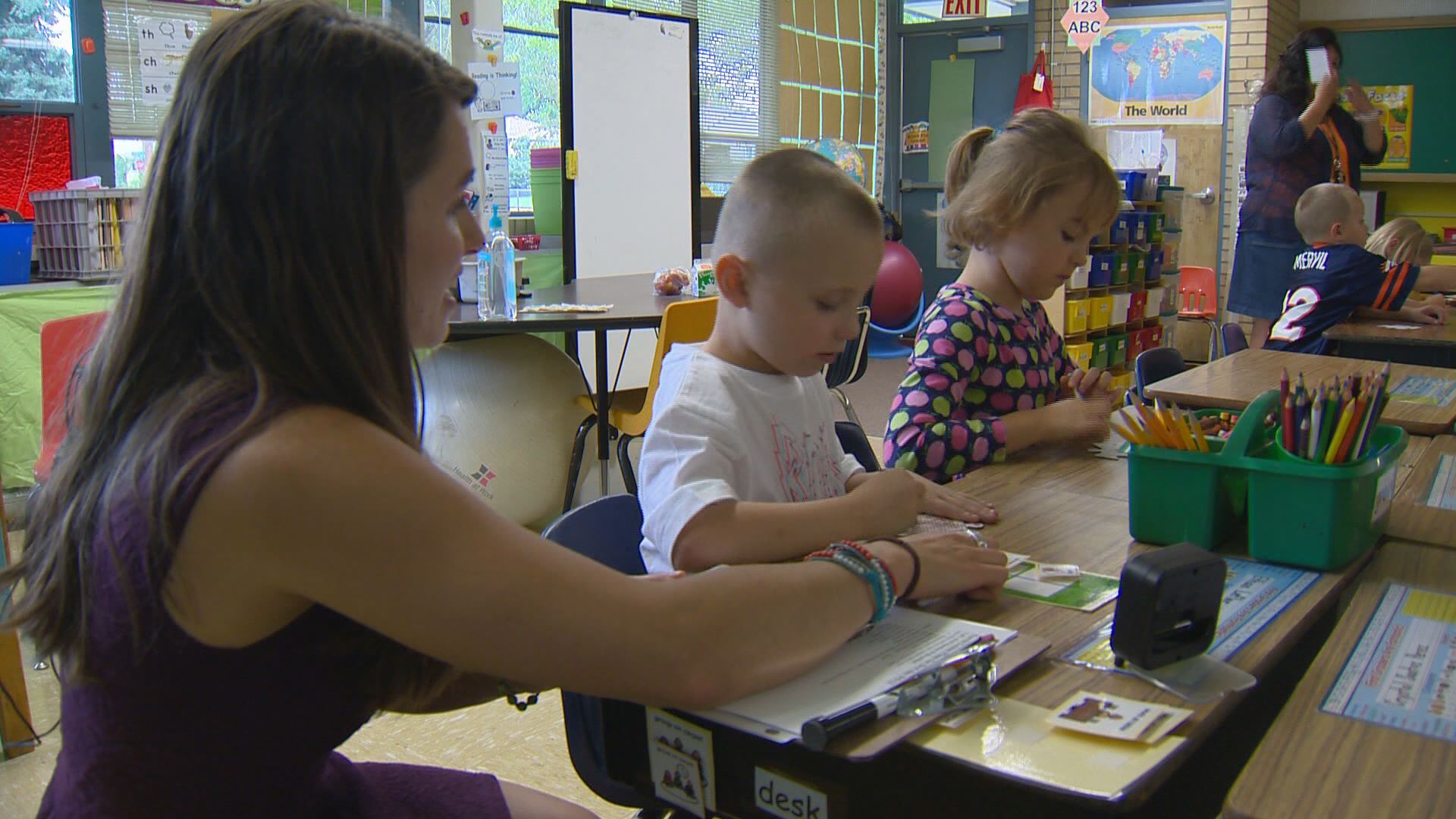

Before Ethan Leflar's first day of school, teachers and specialists had a plan. Ethan is a first grader diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder.

"When we work with Ethan, we have to find out what works for him," Cerri Norris, a first-grade teacher, said. "The biggest thing we use is visual cues."

She uses picture cue cards to help Ethan understand directions and what the class is doing next.

"So, what I implemented in there is what's called a 'visual daily schedule,'" Tandis Taj, a speech pathologist, said.

Taj helped developed this plan with the help of his mother, Misty Leflar.

"The way I would describe Ethan's world at school is a team effort," Misty Leflar said.

She says before school started, she was nervous about sending Ethan.

"I was very anxious actually because here's our little boy who's having struggles socially, focusing, and before school he wasn't talking a whole lot," Misty Leflar said.

Misty Leflar says parents of special-needs children should not be afraid to speak up and help develop what's right for their child.

"It required me to talk to a lot of people, make phone call after phone call in the school systems to make sure my voice was heard," Misty Leflar said. "And, don't feel like it's overstepping."

The Englewood School District is a small district with funding issues. Taj says it's imperative for staff members to work together to find creative solutions to meet the needs of special education.

"The nice part of that is because there is less of us, we can communicate easier," Taj said. "We can communicate faster. We can collaborate better."

The teacher, the specialist and the parent all say the plan is working.

"When he's in here with me, he's working on social, language skills," Taj said.

Ethan gets speech therapy. He is aided by a paraprofessional in class in addition to the attention he receives from Norris.

"It's a juggling act," Norris said.

This classroom also uses iPads almost full time.

"Anything moving on the screen for him, that's very interesting to him, and I do believe that helps him focus," Misty Leflar said.

Norris says it can also be a distraction.

"The iPad has been a blessing and a curse," Norris said. "It's so easy to go into another app, and so Ethan generally wants to do what he wants to do."

He wants to do math. Misty Leflar says the iPads have helped her son grow, pass quizzes and win math awards.

"He's doing tremendous," Misty Leflar said.

As the school year winds down, Ethan still has tough moments. But, Norris says their strategy worked.

"Overall, it's gone really well," Norris said. "I've seen a lot of growth in him. He does reading with me, and he's grown tremendously in reading."

Academic growth and social development were the big goals for Ethan this year.

"The visual schedule, checklist, have all worked really well with him. They still work when I show him the schedule or the clip or picture cue. He still follows along really well. So, we'll pass those along to a second grade teacher," Norris said.

Teaching kids to think and drawing out their opinions are the heart of the Common Core, the new academic strategies shaping Colorado's new academic standards.

"The Common Core really focused on tying literacy into the content areas and also problem solving and critical thinking," Cerri Norris, a first-grade teacher, said.

Norris wants her students to learn skills they will use as adults.

"This is where we want our kids to be when they're 18 years old, so now, we need to plan backwards," Norris said. "So, if these are the skills they need when they are 18, what does it mean that they should be able to do when they're 6 years old?"

In 2009, leaders from 48 states, two U.S. territories and the District of Columbia worked together to define what essential values each state should build into their academic standards. The Common Core is meant to serve as a guide not as a mandate.

"The Common Core standards are definitely more rigorous," Norris said.

Donna Lynne is president of Kaiser Permanente of Colorado. She is also part of a group of business leaders supporting Common Core practices in the classroom.

"For the most part, critical thinking is the way most businesses operate," Lynne said. "Like any business, you want standards – whether it's standards around how your workers do their work or who it is that's coming out of high school."

Norris understands that Common Core has launched political debates around the nation because it is a shift in teaching.

"I know teachers who love the Common Core, and I know teachers who really don't love the Common Core," Norris said. "But, I think the idea of national standards for education is long overdue."

As the academic standards change, standardized tests must change, too. Testing is a perpetual issue for teachers. In Colorado, third grade is the first time students take the traditional standardized tests. But, that does not mean students are not tested in first grade.

"It takes a lot of time," Norris said.

She has to perform her assessment tests face-to-face with each student.

"Just because it's one-on-one, that makes it different. I have to listen to students read, ask them questions about what they read," Norris said. "Also, when they come into the beginning of first grade, they're starting at all different levels."

This is all part of the how all teachers across Colorado have to see if new academic standards influenced by the Common Core are being met. But, when she's testing, she's not teaching the other kids.

"Instructional minutes are precious, and we don't want to waste any of those instructional minutes on tests that aren't going to be helpful for us," Norris said.

Eva Pasiewicz is the principal of Cherrelyn Elementary. She says testing poses a difficult balance for teachers.

"Sometimes that's hard because it does take away from a lot of instructional time. But as long as we use it, it's time well spent," Pasiewicz said. "A teacher also needs to know how well instruction is working."

Testing also equates to half of a teacher's performance evaluation. Norris says that creates an uncomfortable reality.

"The way the policy is set up, it doesn't create a good environment for me or for collaboration amongst other teachers," Norris said. "We think about who's in my class, and what kind of scores I'm going to get from what kids. That's not how a teacher should be thinking."

Now, starting this year, the whole system of standardized testing is changing. Student from third grade through 10th grade will now take a new set of tests calls CMAS and PARCC. These are not standard, fill-in-the-bubble tests, instead they're administered online.

"The students are more engaged during the testing because it's online and hands-on," Pasiewicz said. "They're manipulating a lot of things on the screen. So, I think our overall results will be better because the students are more engaged."

She says the results will be returned much quicker, a matter of minutes instead of months. It is another evolution that is testing teachers.

"It's just getting harder and more complicated every year since I've been teaching," Norris said.

At 6 p.m. on Saturday, Aug. 30, 9NEWS will air a 30-minute documentary called Class of 2025, chronicling the entire year in first grade. The program will be rebroadcast on Saturday, Aug. 30 at 9:30 p.m. on Channel 20.

(KUSA-TV © 2014 Multimedia Holdings Corporation)