DENVER — A drug company has found a multimillion-dollar, taxpayer-funded boon to its bottom line by promoting its addiction medication inside jails and prisons across the country, according to a six-month investigation by 9Wants to Know.

In Colorado, as Alkermes’ sales reps promoted Vivitrol to sheriffs, court officials and the head of the state’s Department of Corrections, the Medicaid budget for the opiate addiction medication jumped 6,500% between 2013 and 2018.

Alkermes says it’s merely keeping corrections leaders “up to date on existing and evolving practices,” but a study on its own website admits its product is no more effective than a more studied and less expensive alternative to Vivitrol.

Desperate for solutions to an ongoing national crisis surrounding opioid addiction – a crisis the Centers for Disease Control reports kills upward of 130 Americans a day,-- politicians and members of the press alike have found themselves eager to help market the drug despite concerns over its relative effectiveness.

As one expert in addiction treatment told 9Wants to Know, it’s not that Vivitrol is ineffective when it comes to treating opioid addicts -- it certainly has its success stories -- it’s just that he believes it’s difficult for the makers of the “darling of criminal justice” to justify its $700 to $1,300-a-shot price tag.

“Don’t believe the hype,” explained Northeastern Health Law Professor Leo Beletsky. “A lot of time it’s the taxpayers who are on the hook.”

CHAPTER 1

Justin Singer, 28, fell in love with Vivitrol the moment someone inside the Jefferson County Jail told him about it.

“It’s going to give me some extra accountability,” Singer said last October. “It gives me hope.”

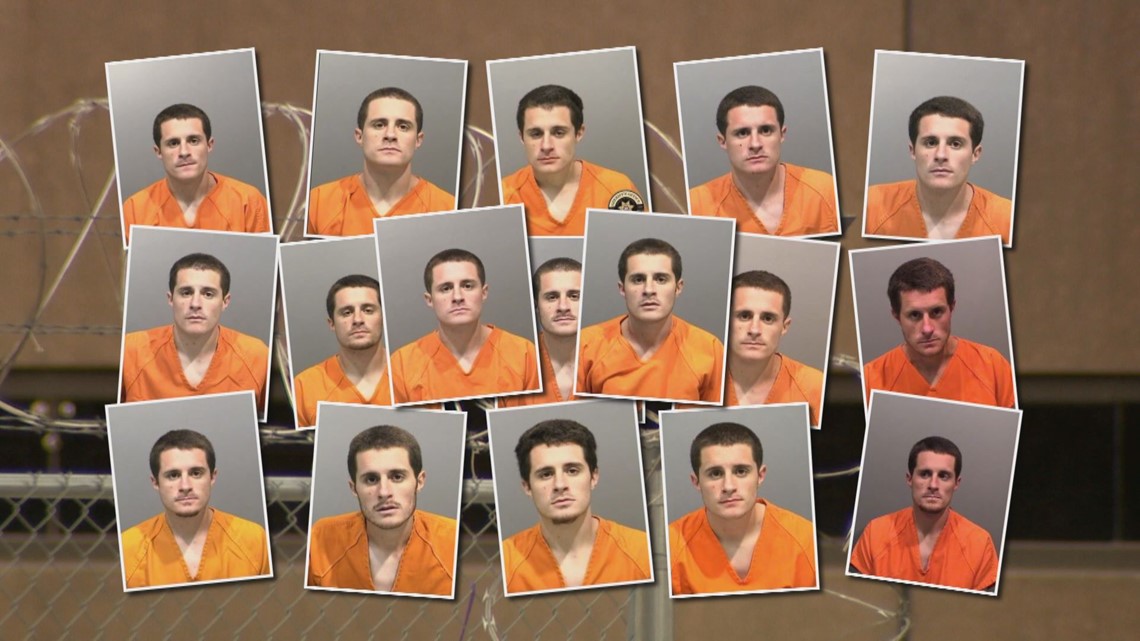

With 17 mugshots to his name in Jefferson County alone, the repeat offender had reason to want to turn his life around.

A self-proclaimed addict since he was a teenager, Singer blamed his more recent use of heroin for getting him into substantial legal trouble.

“I feel like this is going to be a battle for the rest of my life,” he said.

Last year, he pleaded guilty in a felony ID theft case.

“I was caught with some stolen credit cards,” he said.

The money was meant to go toward feeding his addiction, he said.

When 9Wants to Know met him, he was two days removed from his first Vivitrol injection and one day away from getting out of jail.

“I’ll take it for as long as God needs me to,” he said.

Approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat opioid addiction in 2010, Vivitrol – in simple terms – blocks one’s ability to get high on all opioids for approximately 28 days.

It blocks the receptors in the body that are triggered when someone uses heroin, for example.

Use it once, you’re almost certainly going to stay clean for 28 days.

Jefferson County Sheriff Jeff Shrader knew little about Vivitrol at first.

“We heard about it through our medical vendor and the pharmaceutical company that produces it,” he said.

When Shrader was told Vivitrol -- unlike more studied forms of addiction treatment like methadone and buprenorphine – doesn’t contain any opioids, he agreed to let inmates in his jail start taking it just prior to release. It’s non-addictive. He liked that.

So did Singer.

“It’s going to help me push forward into the life I want to live,” he said.

The injection isn’t small and is administered via the buttocks.

“It hurt a little bit,” he said. “I’m proud to be the first one to do it.”

As part of the jail’s Vivitrol program, Alkermes agreed to provide the first shot to inmates for free just prior to release.

The second shot would be the newly-released inmate’s responsibility. Singer expected Medicaid to pay for it.

9Wants to Know, as of the most recent data available, has found 324 Colorado inmates in both prisons and jails have received free Vivitrol shots just prior to release.

At least another 86 people on parole have received the shot as well.

Vivitrol is frequently meant to be taken for six to 12 months straight.

Singer was blunt when asked what would happen if he didn’t have Medicaid to pay for the additional shots.

“Without it, I probably wouldn’t be able to take [Vivitrol]. You know what I mean?” he said.

CHAPTER 2

Cathy Traugott’s job with the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing – or HCPF – is to monitor spending on each and every one of the tens of thousands of prescription drugs Colorado’s Medicaid patients take.

It’s a daunting task.

“Any of the drugs that are FDA-approved and for which there is a rebate agreement in place, Medicaid must pay for,” she said.

In 2013, HCPF reported to 9Wants to Know it spent $118,600.90 on Vivitrol in Colorado. Last year, it spent $7,931,904.11 -- a more than 6,500% jump.

“It’s important to remember that Medicaid expansion went into effect in Colorado in January 2014, which may account for part of the increase seen after 2014," Alkermes wrote in a statement.

But a closer look at the numbers suggests the bulk of the increase came well after expansion took place.

INFOGRAPHIC: Colorado Vivitrol spending habits

For example, in 2014 Colorado’s Medicaid program reported to 9Wants to Know it spent $373,624.11 on Vivitrol.

In 2015, two years after the expansion, the number went up to $1,613,258.27. In 2017, spending went up to $5,497,798.09.

Colorado’s neighbors have experienced a similar jump in spending.

INFOGRAPHIC: Regional Medicaid spending on Vivitrol

“It has gone up a lot. I think more people know about it, but that doesn’t answer the whole question," Traugott said, acknowledging the sizable increase.

Colorado’s Medicaid program does receive a rebate from Alkermes that results in a per-shot price tag of closer to $700 than the list price of close to $1,300.

“It is critical that we also balance the cost of Vivitrol against the cost of not offering treatment that’s best suited to the recovery goals of an individual with OUD [Opioid Use Disorder],”Alkermes said in a statement to 9Wants to Know. “Failure to offer such individualized treatment can have negative consequences on not only health outcomes and costs, but more importantly, on human life.”

To see full statement, click here: http://bit.ly/2J9PlSo

9Wants to Know found a large increase nationally for Vivitrol by the Medicaid program as well.

INFOGRAPHIC: National Vivitrol Spending

In 2013, according to data provided by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), total spending on Vivitrol went from $14.3 million in 2013 to $209 million in 2017.

That’s close to a 1,400% jump.

Certainly, not all of it is due to jail and prison Vivitrol programs, but it’s clear the company has targeted state and local officials to help it expand the reach of its product.

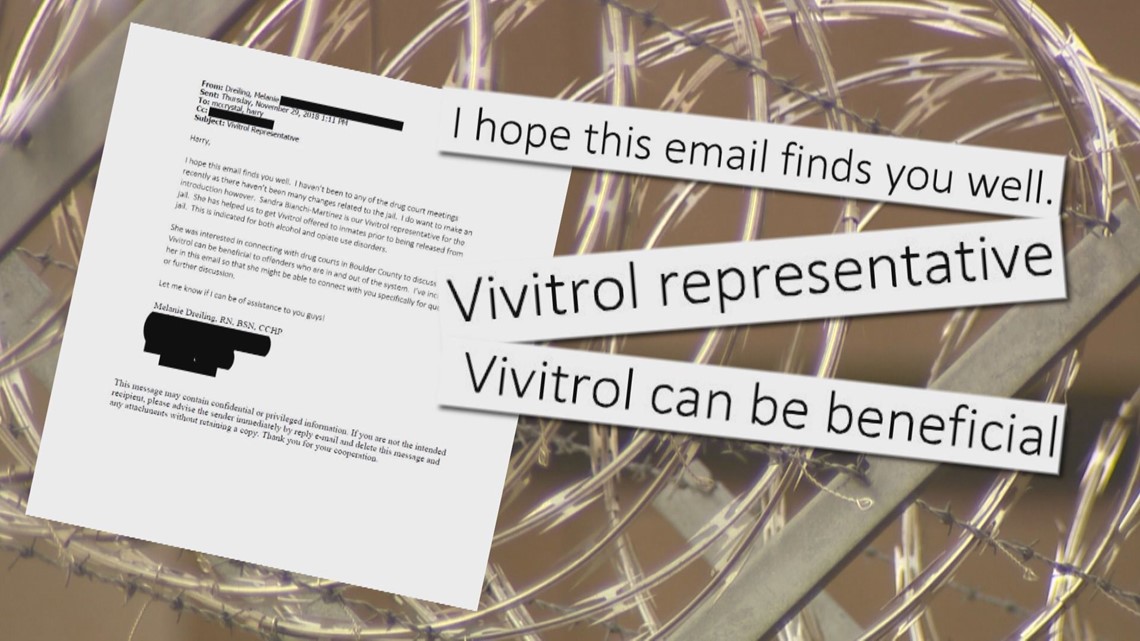

Through open records requests, 9Wants to Know also obtained emails sent by an Alkermes sales representative to both Boulder County jail officials and the Colorado Department of Corrections.

“Samples have been shipped. See tracking info below. Happy Halloween,” read an Oct. 31, 2018 email from an Alkermes sales representative to a pharmacy manager with the Colorado Department of Corrections.

A July 2018 email from an Alkermes sales rep to the medical supervisor at the Boulder County Jail read, “I hope your summer is going well. I will be up in Boulder on Friday. Would you have any time to meet?”

“I can be available in the morning on Friday. Any time before 11:30. Does that work for you?,” replied the medical supervisor.

CHAPTER 3

Beletsky, an associate professor of Law and Health Sciences at Northeastern University, doesn’t exactly fault Alkermes for giving shots away to Colorado inmates like Justin Singer.

“It’s a brilliant business strategy where you provide the first shot for free and then insurance is billed for each subsequent shot,” he said.

There’s just one big problem with the cost of Vivitrol, he said. He doesn’t believe it’s worth it, at least when compared with other types of medication assisted treatments (MAT) like methadone and buprenorphine.

“I don’t believe so,” he said. “There’s nothing about this medication that makes it reasonable to cost $1,200 a shot.”

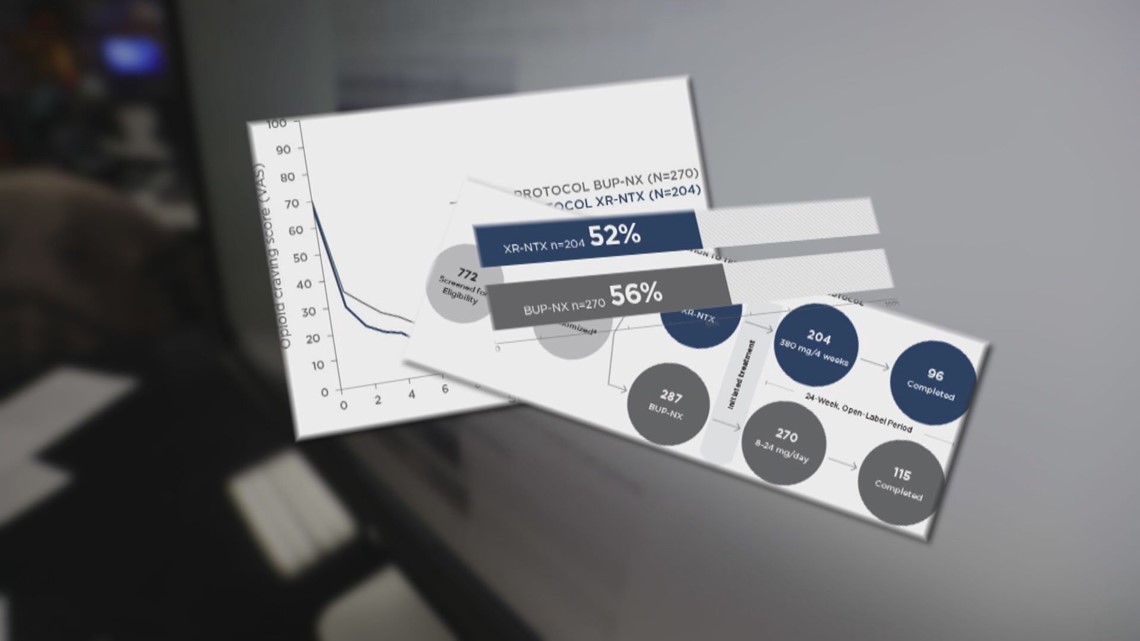

Part of the problem is that, to date, studies have found Vivitrol no more effective than its more well-known counterpart oral buprenorphine-naloxone. A study featured on Alkermes’ own website suggested both drugs experienced relapse rates of more than 50% within the first six months of initiating treatment.

The same study, finalized in late 2017, did suggest a stronger decrease of cravings with Vivitrol initially, but after 24 weeks the cravings of patients on both drugs were roughly the same.

Buprenorphine-naloxone, also known as generic Suboxone, runs close to $60 – with a coupon – on GoodRX as of early May for 28 sublingual tablets.

On the same website, Vivitrol runs – with a coupon – a little more than $1,300 a shot.

Vivitrol remains without a generic counterpart and, as of now, enjoys patent protection on injectable naltrexone for another decade.

Last year, Alkermes reported $302.6 million in net sales for Vivitrol. It’s a critical drug for a company that otherwise continues to lose money,

In 2016, at the direction of the Washington State Legislature, the Washington State Institute for Public Policy concluded in a study that Vivitrol stood a 0% chance of being cost effective.

“The research evidence shows that injectable naltrexone [Vivitrol] reduces substance misuse. However, the monetary benefits do not outweigh the costs of the medication,” reported the WSIPP study.

“We find the injectable naltrexone reduced opioid use for people in the criminal justice system, but does not have a reliable effect on criminal recidivism,” the study also concluded.

In a response to 9Wants to Know, Alkermes said, “When it comes to OUD, it’s critical to understand that the three FDA-approved treatments—buprenorphine, methadone and extended-release naltrexone—are not interchangeable. Therefore, there are inherent challenges and limitations to studies like this one…. Cost analyses that suggest these options are interchangeable may create barriers that inhibit patients from getting the treatment they want and need.”

It’s unclear just what kind of impact the WISPP study had in the state in which it was conducted. 9Wants to Know found during the year prior to the study’s release (2015) Washington’s Medicaid program spent $309,761 on Vivitrol.

Last year, it spent $11,634,516.

CHAPTER 4

Justin Singer left the Jefferson County Jail on October 3, 2018, on Medicaid and full of optimism.

One Vivitrol shot in, Singer believed his life might finally be back on track.

Twenty-three days later, Weld County Sheriff deputies arrested him while he was trying to sleep in a car on a rural road.

“I used methamphetamines a few times before I got here,” Singer told 9Wants to Know from the Weld County jail. Vivitrol does not have the same blocking ability with meth than it has for opioids.

“I got a possession charge,” Singer said.

He never made it to get the second shot of Vivitrol. He said he was planning on it.

“I’m an addict. You know what I mean? We are going to have relapses and stuff,” he said.

9Wants to Know spent weeks tracking other inmates profiled in other television news stories on Vivitrol and found a number of stories like Singer’s.

“If these inmates in Kentucky are as successful as Jordan West, families and neighborhoods devastated by the epidemic of opiate addiction may finally have a way to combat it,” the reporter said.

Less than two years later, West was arrested on a heroin possession charge.

Early last year, WBIR-TV in Knoxville, Tennessee ran a success story on the Knox County Vivitrol program on a man named Gregory Fox.

“I’ve not had any issues,” he said at the time.

A year later, Fox was back in jail.

Patrick Sauble of New Jersey and Chase Callander were both profiled in local media reports on jail Vivitrol programs.

Both talked highly of Vivitrol.

Both ended up dying of overdoses after voluntarily discontinuing use of the drug.

“Relapse is a very real and pervasive issue for people struggling with opioid dependence,” read a statement from Alkermes. “While the vulnerability to overdose outlined in Vivitrol’’s prescribing information is clear and always communicated by Alkermes, we firmly believe that the greatest risk for opioid overdose is in patients who are not getting any treatment at all.”

To people like Beletsky, it’s simply a sign that addiction treatment will have to go beyond one shot.

“We’re hanging our hat and pinning our hopes on the idea that you can just give people a shot and they’ll be all better,” Beletsky said. “Unfortunately there are no easy fixes to complex problems.”

Katie Wilcox contributed to this report.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS | Investigations from 9Wants to Know