DENVER — More than 50 years after the unsolved murder of a young mother in Denver, her family’s hope for answers is up against a bitter reality – the original police file has been missing for at least a decade, lengthening the odds the killer will ever be identified.

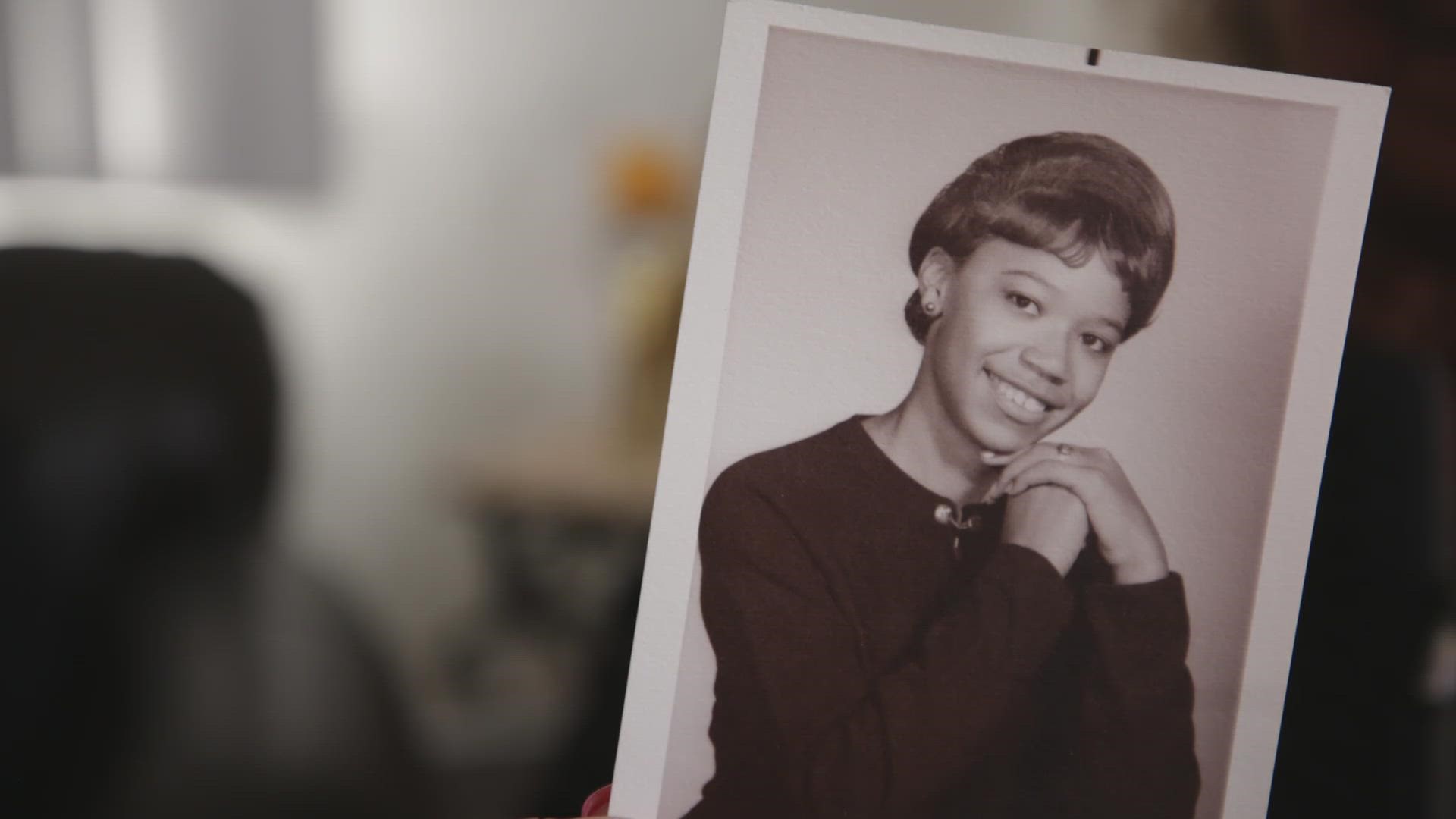

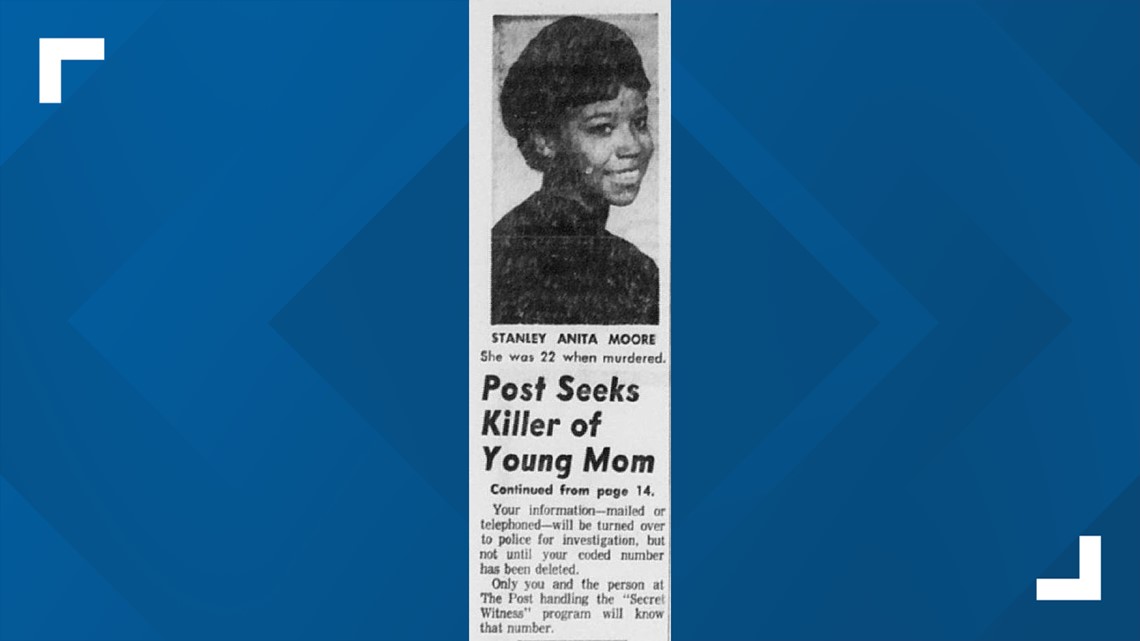

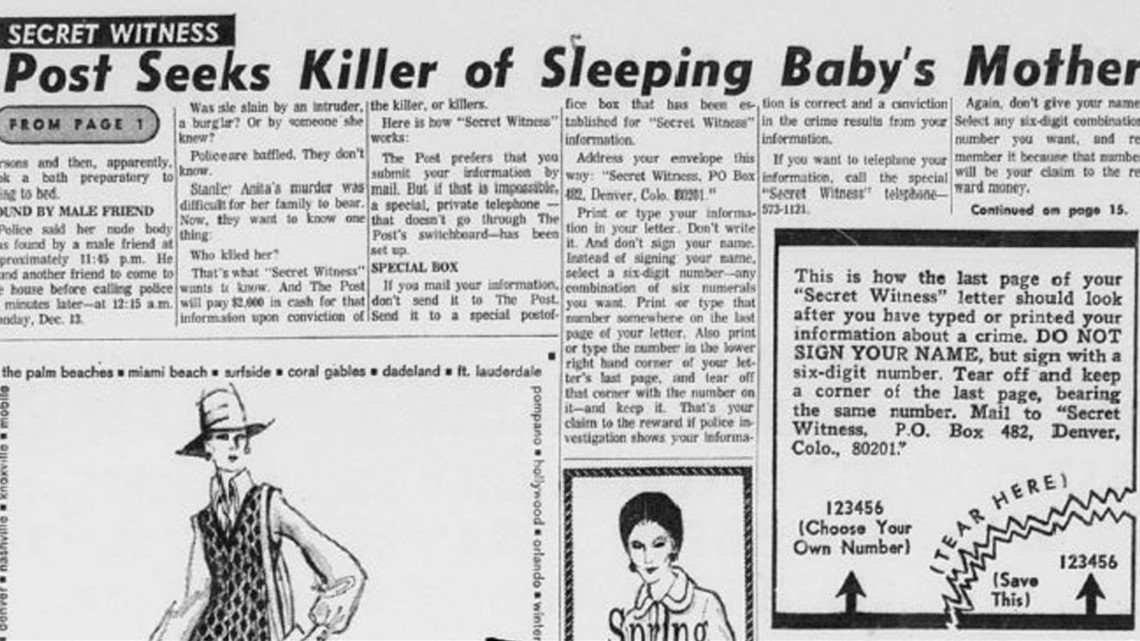

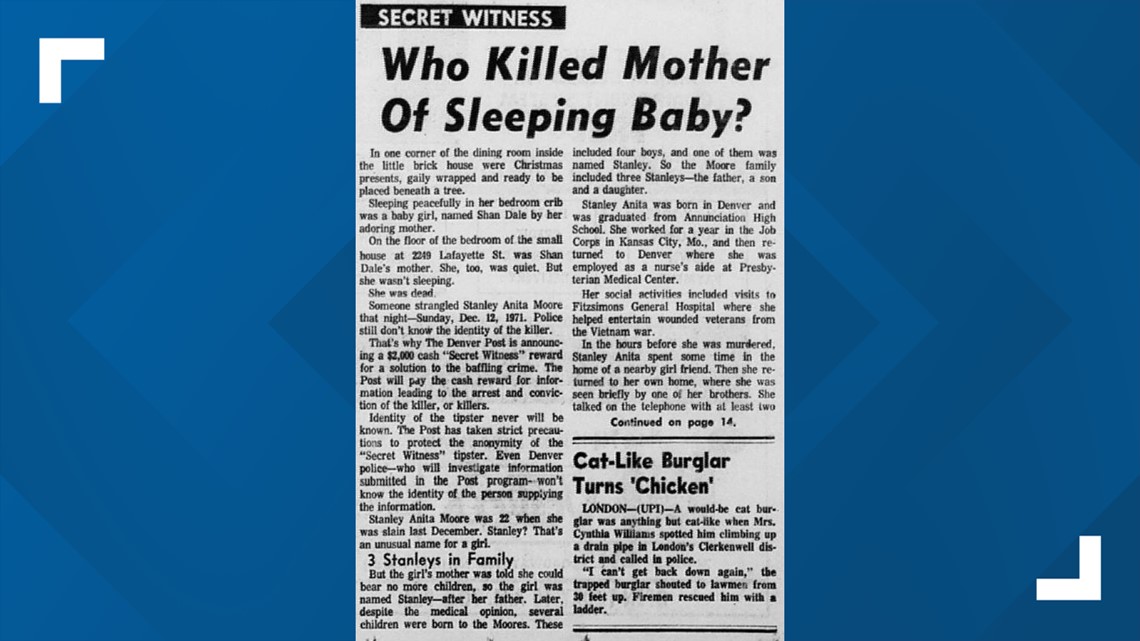

Stanley Anita Moore – Stanita to her brothers and sisters – was 23, a young mother, and a nurse aide working at Presbyterian Hospital when someone strangled her on Dec. 13, 1971, as her 18-month-old daughter slept in her crib in another room.

“I didn’t get to know her, and I wish I could have,” Shan Dale Hornbuckle, that daughter, said.

The murder got a brief mention in the newspapers, and a larger story in The Denver Post a few months later touting a $2,000 reward. But then it faded from view.

“It just seems like it lasted a week or two, a month or two, and then nothing,” said Sandra Fisher of Denver, one of Stanita’s sisters. “And then every year after that, we just kind of wondered, when are they going to find something?”

Solving it now will be a monumental task.

Denver police spokesman Doug Schepman confirmed to 9Wants to Know this week that the case file is missing. All that exists, he said, are some handwritten notes from the crime lab, a brief entry of the incident in a daily ledger, and the autopsy report.

After a half-century of hoping that someone would be held accountable, Stanita’s family wonders if the fact she was Black meant her case didn’t get the investigative effort it deserved.

“She was a Black lady down in the ‘70s,” Hornbuckle said. “Did they not care?”

***

Stanley Anita Moore came by her unusual name as a result of the hopes of her dad, Stanley Moore, for a son.

“On the fourth time my mother got pregnant, he said, this is going to be a boy,” Fisher said.

Instead, it was another girl.

“And he said no, we’re going to call her Stanley Anita,” Fisher said.

Boys came along later, and her family took to calling her Stanita.

“She was a tough cookie to get along with,” said Stephen Moore, one of her younger brothers. “I didn't have to worry about the bullies if I was with Stanita. She would take up for me.”

Stanita and little Shan Dale were living at a home in the 2200 block of Lafayette Street when she was killed.

“It was late, and I was asleep,” Fisher said. “Somebody called us and said that something had happened to my sister and that we needed to get there right away.”

“I just remember my mother crying and telling me that they had to leave,” Moore said.

One of Stanita’s older sisters adopted Shan Dale – and her aunts and uncles and cousins played starring roles in her childhood.

“I just had a whole lot of love,” Hornbuckle said.

***

In the meantime, the family’s relationship with police was rocky.

One of Stanita’s brothers had a tense exchange with police.

“He was dead set on getting somebody for it,” Moore said. “He was pretty angry.”

“The police kind of got a restraining order, I think, against us,” Fischer said. “But we weren't trying to do any harm – we were just trying to find out what really happened to her.”

Then came the blow in a meeting that Fischer said was a decade or more ago. In a discussion with detectives, Fisher said she asked what kind of information they had in the case.

“They said there was a fire at the police station and all her information had been destroyed,” she said.

Schepman, the Denver police spokesman, said it was not clear what happened to the file, writing in an e-mail that “it is unknown if it was lost to fire or water damage, was misfiled in the archive, or was possibly checked out by an investigator and not returned.”

The file has apparently been missing since at least 2012.

“How are we ever going to solve this problem if we have no information on anything?” Fisher asked.

***

Solving decades-old murders are difficult in the best circumstances.

“All cold cases are challenging because they weren't solved for some particular reason,” said retired Arapahoe County sheriff’s investigator Bruce Isaacson. “Is that because of lack of evidence? Is that lack of cooperation from witnesses? Is it sometimes the department didn't have the time or the experience or the ability to investigate the crime to its conclusion?”

Isaacson spent the last decade of his career investigating cold cases.

Over that time, he’s seen a lot of the things that can handicap an old case. Gloveless detectives handling evidence. Records kept haphazardly – if at all. Evidence that disappeared sometime over the years.

“Cold case investigation requires thinking outside the box and looking for records and evidence that sometimes doesn't follow the general investigative path,” Isaacson said. “I think generally in cold cases, as time moves on, it sometimes damages the case.”

That’s the bad news, Isaacson said. But there can also be an upside.

“Alliances change over time,” he said. “Maybe 20 years ago, a person wasn't willing to tell us what they knew about a murder case, for whatever reason, they were afraid of the person or they had a relationship with them where they weren't willing to go against what they thought was right or wrong for that relationship. Now it's 20 years later, and those relationships have changed.”

Watch below: Reporter Kevin Vaughan discusses the cold case.

“My mother and dad, they tried to find out something before they passed away,” Fisher said. “And they didn’t do it. So in our lifetime, we would like to have this case solved.”

For that to happen, it may require the kind of situation that Isaacson described – somebody who didn’t talk to the police in 1971 talking now.

Without the case file, finding the someone who might have information could be more challenging.

That the investigation is at this point raises questions for Stanita’s family.

“It doesn’t seem like they really did a lot, to try to bring this to justice,” Fisher said. “At the time, you know, I didn’t consider color. You know, I was just worried about her, and finding out who did it.”

For Stanita’s daughter, the failure to solve the murder has left her feeling “like nobody – like she was nobody, I’m nobody.”

“I would like for somebody to come forward – so she can rest, and I can rest,” she said.

Contact 9Wants to Know investigator Kevin Vaughan with tips about this or any story: kevin.vaughan@9news.com or 303-871-1862.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Colorado cold cases