MESA COUNTY, Colo. — The day after Christmas 2017 was payroll at Carbondale's Tumbleweed Dispensary, and general manager Zackaria Green slid money into envelopes.

When he got to Jonathan Ellington's, Green tucked 10 small blue pills in alongside the cash. He had purchased 12 of the tablets, stamped to look like oxycodone, earlier in the day from his dealer for $25 apiece. Ten for Ellington, two for him. He texted Ellington that'd he drop the envelope at his duplex that night.

The two men were drawn together by their jobs and their substance use. Green had struggled with heroin and opioids for years and had recently relapsed. Those closest to Ellington didn't know he'd started using again after years of sobriety, and he asked Green to "please" not mention the contents of the envelope to anyone else. Green assured him that his "secret is safe," and then he sent his friend a heads-up: These pills are laced with fentanyl.

The pills had traveled a far distance to reach this point, from a Mexican resort town to a quiet border station, up through the American southwest. They'd landed in the hands of the patriarch of a family-turned-drug network that dominated the early fentanyl trade in western Colorado. Ellington would never know Bruce Holder, a father who friends said didn't look like a drug dealer, but who cut corners and sought an easy life. He sold his pills through his family. He and Ellington would become inextricably linked.

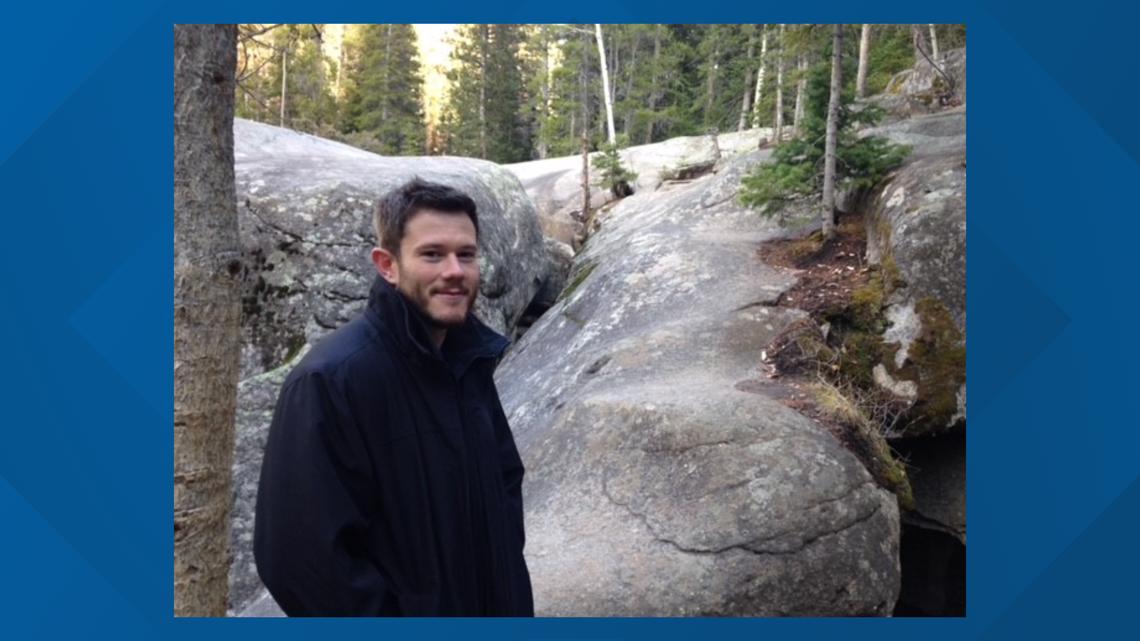

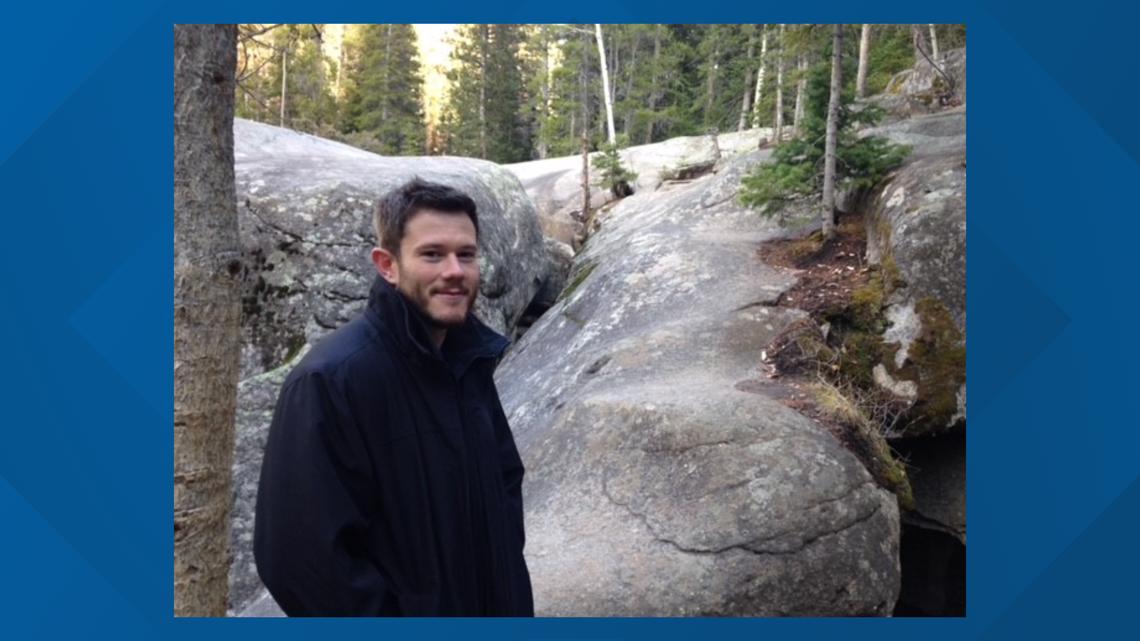

Dec. 28, two days after Green dropped off the envelope, Ellington didn't turn up for his shift at his other job, as a bellman at Aspen's upscale Hotel Jerome. He was a reliable, dedicated worker; he'd previously been employee of the month. It was unlike him to miss work, and his roommate called Lynsey Powell, who was home sick at the duplex the three of them shared, to check on him.

Powell didn't think Ellington was home: He would've been using the kitchen, or listening to one of his comedy podcasts. The duplex was quiet.

She knew he'd struggled in the past. He'd moved to Colorado from northern Kentucky to start over, to get away from an addiction that had spiraled after a series of high school knee surgeries. She knew he was strict about his routines: Gym, laundry, work. And she knew he'd been off of those routines recently, after he'd injured himself several weeks before.

And as Powell climbed the stairs to Ellington's room, her fear grew.

"I just knew that when I went to open that door," she said this spring. "I would not find him alive."

Ellington's room was dark, and it was hard to see. She took another step. Then she saw him, stretched out over a chair. There was a syringe in his lap, a tourniquet between his legs.

She called 911, and two Carbondale police officers soon arrived. The first entered Ellington's room and shouted to the second to bring Narcan, a medicine used to reverse opioid overdoses. Seconds later, he called out again: Never mind. No need.

An EMT crew came and went, their usefulness long passed. The coroner's office took their place. Before the police finished working the scene, a new call came over the radio: Another overdose, this time at a dispensary.

As Powell found Ellington, Kyra Karrick found Green. He had taken a 15-minute break, shortly after the time police arrived at Ellington's duplex. He sat in his car in the dispensary's parking lot and smoked one of the pills he'd purchased. He put the vehicle in reverse and promptly lost consciousness, his car rolling slowly into a dispensary wall.

When he didn't return, Karrick, the assistant manager at the dispensary, went looking for him. The doors to the car were locked. Karrick raced back to the building and returned with a stool, breaking it against the vehicle's windows. She tried a hammer next and after a few swings smashed through the window. Her hands bleeding from the shattered glass, she pulled Green from the car. She gave him CPR until EMTs — the same crew that had left Ellington's duplex — arrived.

The EMTs didn't have Narcan handy. But a responding police officer did. He, too, had just been at Ellington's. He handed the Narcan to the EMT, who shot it into Green's nostril. He regained consciousness, grumbling, as if he'd awoken from a deep sleep.

Ellington was not the first to die after taking the small blue pills smuggled into Grand Junction in the glovebox of a white Honda. Green was not the first to narrowly survive them. Neither would be the last.

They were canaries in a coal mine of what has become the worst drug overdose crisis in the state's and nation's history, a disaster fueled by a new drug and a nation primed for its arrival. Fentanyl has killed more than 1,600 Coloradans and tens of thousands of Americans in the past three years.

In court documents, federal authorities have linked eight other fatal overdoses, with varying degrees of certainty, to fentanyl provided by the same man and family whose pills killed Ellington. The deaths were clustered together over a 17-month stretch in 2017 and 2018. During that time, law enforcement said, Bruce Holder was the largest fentanyl dealer in Western Colorado, perhaps the largest in the state.

A message sent to Holder’s attorneys seeking comment for this story was not returned. The Colorado branches of the U.S. Attorney’s Office and the Drug Enforcement Administration declined to comment.

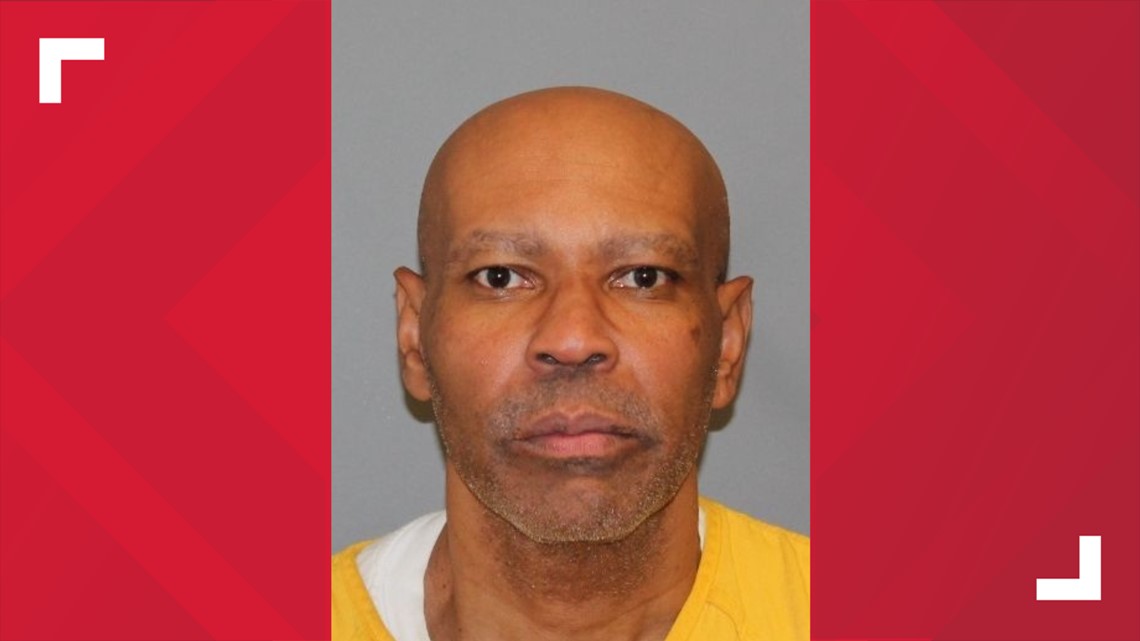

Holder was a 50-year-old California foster kid who'd followed a boyhood friend to the Western Slope. Physically imposing at 6-foot-6, one family member described him as nerd-looking with his thick black glasses and high-water pants. Back when he moved several decades ago, his friend Jerry Huggett said, Holder seemed settled: He mowed lawns for Huggett's grandmother. He had a stable job at Louisiana Pacific, the building supply company. He liked rebuilding cars and wanted to be a musician.

Holder was likable but manipulative, Huggett said, and ultimately, he wanted an easy life.

The desire for that easy life would devastate several families. The dead would include three teenagers. One dreamt of being a rapper, another of playing in the NFL, the third of spending his life working with his hands. Three mothers died. Together, they left behind seven children. One died as potatoes cooked on her stove, and her boyfriend, revived by Narcan, took his own life after he was released from the hospital. A beloved brother and uncle was found, abandoned, in a stranger's driveway.

Like so many others who became addicted to opioids over the past 25 years, many of the family's customers began using after they were prescribed legitimate prescriptions or after they were injured. The pills that killed them came from Mexico, their ingredients shipped from China, the same pipeline that has dumped an ever-increasing amount of fentanyl into the state and country.

The events of late December 2017 sparked an investigation that ended in the arrest of more than a dozen people. It was Ellington and Green, each spiraling due to a devastating disease, that focused attention onto the man who had turned those closest to him into a network of drug dealers.

It was Green's survival that helped lead local and federal law enforcement to Bruce Holder's modest Grand Junction home, and it was Ellington's death that enabled prosecutors to seek a first-of-its-kind conviction against him.

This story, the most complete account of that family and the deaths that followed in their wake, is based on more than 2,000 pages of legal filings, court transcripts, autopsy reports and other public records, as well as interviews with more than a dozen people, including family members and friends of those who died, health and law enforcement officials, and others with direct knowledge of the situation.

It's a story of the beginning of Colorado's entry into the third, and worst, phase of the opioid epidemic, one that's unspooled out of control beyond the family that dominated its early days, and it's the story of the first time a Colorado jury convicted a man for killing another person with fentanyl pills.

Border agents stood outside of Bruce Holder's Buick, their guns drawn.

He and his wife, Marie Matos, were at a small crossing in southern Arizona. It was fall 2016, and it was their first time making a trip that would soon become a twice-monthly trek. They'd crossed into Mexico without incident after a lengthy drive from Grand Junction, but Holder was a felon with drug and gun convictions. When he crossed back into the United States, agents took notice.

After half an hour, he was let go. On subsequent trips, Holder would get out of the car at the border and walk across, dealing with agents on foot without drawing attention to the car and its contents. He would then meet Matos at a gas station that sat alongside the guarded road leading to and from the United States.

The crossing’s buildings are salmon pink, nestled at the base of a steep hill that overlooks Mexico. The American side, known as Lukeville, is barren — desert, desiccated vegetation, dirt roads with blind turns. Past the metal slats of the border wall, built atop plants used by indigenous peoples to treat heart disease and menstrual cramps, is a busy highway, homes, a church. Lukeville is 2½ hours south of Phoenix, so remote that the Air Force uses the surrounding desert as a firing range, where warplanes obliterate cacti and sand.

The couple was returning from Puerto Penasco, a resort town on the coast of the Gulf of California. The town is known for its increased cartel activity, and is home to an old friend of Holder’s. He had several aliases, but the family knew him as Chon. Holder and Matos had driven down to the Mexican coast in their Buick and stayed at Chon’s condo. When they turned back north, they took with them a white Honda Accord, a gift from Chon. In its glovebox were vacuum-sealed bags with at least 2,000 blue fentanyl pills.

It was not Holder’s first experience with drugs. He’d been arrested in 1993 for selling weed, meth and cocaine, then again in 2003 for trying to buy a gun illegally. He’d gotten back into selling drugs after his release in 2008, and he switched to pills after making a deal to swap weed for his neighbor’s Percocet prescription, prosecutors say.

His shift came amid a broader, deadly turn in the drug market. The aggressive marketing and prescribing of painkillers had flooded the nation with opioids well before Holder’s first trip in 2016. By then, heroin had flourished as a cheaper alternative to pills, and it was immune to subsequent regulatory crackdowns. But to make heroin, poppy plants have to be grown and seedpods scraped. This requires cultivation, manpower. It’s vulnerable to weather and climate.

Fentanyl can be made in a warehouse year-round. First synthesized 60 years ago as a safe surgical anesthetic, fentanyl is still used for its intended purpose today. But because it’s cheap and easy to make, it has displaced heroin as the drug of choice for cartels and, as a result, for people with opioid-use disorders. It’s far stronger than its plant-based cousin at a fraction of the dose and cost. Its high is more fleeting, its dosage more variable, its demand more consuming.

That demand found the Western Slope. Matos, who connected with Holder over Facebook after he was released from prison, soon began making the drive to Mexico twice a month, bringing back at least 2,000 pills at a time. Sometimes Holder would tag along, and sometimes he’d bring his family along to shop, eat, ride four-wheelers and visit strip clubs. For $500 a month, Holder even began renting his own condo in Puerto Penasco.

When Matos would return with the pills, she later testified, Holder would wait for as long as two weeks before he disassembled the dashboard and removed them. Instead of child support, he sent pills to his ex-wife — whom he’d allegedly physically abused and sent to the hospital, according to court documents. When his teenage son wanted more money for basketball gear, he told him he “had to work for it” and gave him pills to sell. His daughter, Lexus, got involved through a friend-turned-customer. His stepdaughter’s boyfriend was a user, too, and he annoyed Holder. So he had his stepdaughter sell to him and to others.

Holder also recruited Matos’ second cousin, a scrawny twentysomething named Christopher Huggett. It was Christopher’s dad, Jerry, whom Bruce had followed to Colorado. It was Christopher who sold the pills to Zackaria Green, the same pills that Jonathan Ellington used before he died.

Holder paid $12 a pill, according to testimony from a DEA agent at his trial. He sold them to his dealers — that is, his family and friends — for more, $17 or $20 each. The end user would often pay $30 apiece, the going rate for the oxycodone 30 milligram pills they were purported to be.

They looked like oxycodone tablets, too: Small, blue, with the manufacturer’s mark stamped on one side and the pills’ supposed dose stamped on the other. But users said these pills were far stronger than the oxycodone they used. Sometimes, that was a good thing. When it wasn’t, these new pills made them dizzy. They vomited and passed out.

Before long, they started to die.

Sandy got the call first from some girls who were out with her son, Daniel. The county coroner would later apologize: This isn't how we notify people, he said.

It was Labor Day weekend 2017. Her husband, D.C., was 1,500 miles away, traveling for work. With her sister and some friends, Sandy had gone up to the mountains outside of their Western Slope home. Sandy and D.C. asked that their last names not be used out of safety concerns.

At that moment, they weren’t on good terms with Daniel, 19, their only child. They’d had an argument, and he wasn’t welcome home anymore. Moving to Colorado as a teenager was hard, and Daniel was impressionable, eager to fit in with the older kids. His parents knew Daniel was smoking weed, and D.C. warned him about taking anything stronger.

Despite the fight, D.C. and Sandy thought things were improving. That summer, Daniel had worked in Telluride, painting and roofing. He’d graduated from high school. Though he was smart and inquisitive — he’d kept batting stats for his first-grade T-ball team — school moved too slowly for him, and he struggled. He could’ve been anything he wanted to be, his parents said, but he wasn’t made to sit behind a desk. He needed to be outside, to work with his hands, to build. That summer confirmed it.

"We're looking at, 'Maybe, oh, maybe he's gonna go take a job some other place. Maybe he likes Telluride, you know, maybe he'll take up skiing,'" D.C. said. "That was one of my biggest passions growing up, skiing. And so maybe he'll take that up when he gets older. You don't think about these little things like the coroner, or the funeral home or, you know, a church … "

Or, Sandy interjected, "planning a funeral for your son."

Citing text message records, prosecutors allege that Daniel died after taking fentanyl pills that he'd purchased from a teenage dealer who bought his pills from Holder and was longtime friends with Holder's son.

D.C. flew home after his son's death, unable to control his tears on the plane as he realized he'd lost "the most important thing in my life." He works in health care. He helps to save people's lives. But there was nothing he could do to save Daniel.

"Not a g--damn thing," he said.

By the time Daniel died on Sept. 1, 2017, Holder was well aware of the strength of the pills he was selling. Months before, in early 2017, a user had warned him about someone else overdosing. Holder, Matos later testified, called Chon to ask what exactly was in those vacuum-sealed bags.

"He said they were fentanyl," Matos later testified. "I asked (Holder) what fentanyl was, and he did a little bit of research with the pill finder app that he had on his phone."

After that, Holder started telling people to cut the pills into halves or quarters; police later seized a pill cutter from his home.

But he did not stop selling. Daniel died months after Holder learned the pills were fentanyl. So did another teenager, Bradyn Heit. He overdosed in July 2017, a month after his 18th birthday. His dreams of playing in the NFL had been derailed by a back injury, and a breakup had shattered him. He was his mother’s golden child, his sister, Brandee Lee Eighmy, said, and 25 days after he died, his mom fatally overdosed, too.

A day after a hammer and some Narcan saved his life, Zackaria Green told a Carbondale Police lieutenant a story.

The police department was concerned, the lieutenant told Green. Two overdoses — Green's and Ellington's — had been reported on the same day, and police wanted to know what caused them.

Green admitted that he’d given Ellington “a few” pills, the ones found in his bedroom after he died. But the rest of Green’s story was, to quote Holder’s defense attorney, “bogus.” He did not say he’d purchased the pills from Christopher Huggett, a close associate of Bruce Holder.

Instead he told the lieutenant about a traveling drug dealer named Chris, a Spanish-speaker from Denver who drove a ‘97 Honda. He told a similar story a week later, when he sat down with the officer again. A DEA agent was there, too.

Green was no stranger to drugs. He struggled with his mental health, and he had an opioid-use disorder. When he couldn’t get heroin, a DEA agent later wrote, Green used pills: He’d purchased pills from Holder’s network frequently and was using the pills daily. He’d overdosed before, too: After smoking part of a fentanyl pill several months before, Green had passed out for hours, foaming at the mouth. He then got sober for a few months, only to relapse in November.

A few weeks later, he walked into Ellington’s duplex with his dispensary cash and 10 pills.

Attempts to contact Green for this story, including through his former attorney and his family, were unsuccessful.

His story of the traveling drug dealer did not placate law enforcement, and his attempt to protect the man who’d sold him the pills was short-lived. In early May 2018, Green got a letter from the U.S. Attorney’s Office informing him he was under investigation for Ellington’s death. Ellington was his friend, and his death had “devastated” him, he later testified. He sent a picture of the letter to Huggett, who began to panic.

"It is what it is, man," Green told Huggett. "I deserve it."

Prosecutors were threatening to hold Green responsible for Ellington’s death. He could spend the rest of his life in prison. In mid-June, he agreed to cooperate and named Huggett. That same month, a man working for the DEA had purchased pills from a user working for Lexus Holder, Bruce’s daughter, in a series of parking lots in Grand Junction.

Three days before Green struck a deal with prosecutors, Andrea Thomas awoke from a dream. It was a "horrific" dream, she said, in which she felt lost and hopeless.

At the time, she thought it was a nightmare, related to the last thing she'd watched on TV that night. But now, she thinks the dream was a sign that the cosmic connection linking mother and child — linking Andrea and her daughter — had snapped.

When her husband left for work that morning, Thomas told him she needed a bit of time to herself. She was at home, in the hills above Grand Junction, alone. Then her phone rang, as Sandy and D.C.'s phone had rung nearly a year before. The dread message was the same.

Andrea got in her car and hurtled toward town. The call hadn't made any sense, and now she had to find Ashley, she had to find Ashley's son, she had to find the rest of her family, she had to call the hospital.

When she called her oldest son,"He answered the phone - just screaming and inaudible," she said. "And I knew he'd gotten the same phone call I had gotten."

Ashley, her boyfriend would later tell police, had taken a pill her boyfriend had purchased from a user who worked for Holder's ex-wife. The woman had described the pills as "cartel pills."

Ashley had been her parents’ first child, and their parents’ first grandchild, and so from an early age she was adored. Her birth father was in the military, and she spent her early years in Germany. With dark hair and big eyes, she stood out among the locals. Outgoing and loyal, Ashley was the sort of person that things seemed to come easy to. She loved the energy of bigger cities, but she never left her home.

She loved late-night breakfast, and when her shattered family walked into her now-empty home that day, they found potatoes in the frying pan, eggs in a bowl. Ashley and her boyfriend had been found unconscious in their car. Her boyfriend was revived. Ashley was not.

After he spoke with police and was released from the hospital, Ashley’s boyfriend killed himself.

Christopher Huggett’s face was on the front page of the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel on July 31, 2018, under a headline about an indictment and a fentanyl overdose. When Marie Matos left the Stinker gas station after her overnight shift, she took a copy of the paper with her.

Huggett had been arrested 13 days before, as he walked across the street from his job to buy a soda. His father, Jerry, was close with Holder, and he'd grown up calling the man uncle. He'd been invited to family barbecues and accompanied Holder on one of his trips to Mexico, where they went to strip clubs, drove four-wheelers and drank heavily. Jerry had warned Holder not to include his son in whatever it was Holder had going on.

But Holder used people, Jerry later said, and Christopher was enticed by the lifestyle his so-called uncle lived.

Then he was arrested for selling the pills that had killed Ellington, his alleged crimes printed in black-and-white on the cover of his hometown newspaper.

Matos took her copy of the paper to a nondescript Grand Junction home, where she and Holder had moved in December, shortly before Jonathan Ellington died. It was larger than the apartment where they'd lived before, but it wasn't exactly a kingpin's lair: Four bedrooms, two bathrooms, a deteriorating white fence and a front yard with a single tree. A DEA agent would later describe it as a mess, dishes and papers and clothes scattered about, the couple's possessions heaped into piles.

Before she went to bed, she handed the newspaper to Holder, and he sat down to read it.

A cousin to Jerry and Christopher Huggett, Matos had known Holder most of her life. Her first memory of him is from when she was 3 years old and he was a teenager. They'd reconnected over Facebook in 2011, three years after Holder got out of federal prison. She'd traveled to and from Mexico at least 25 times at his direction, moving guns, meth and tens of thousands of fentanyl pills. She would later become the first person to testify against Holder. With her own prison term stretching before her, she cried on the stand and said she still loved him.

Matos, who was released from prison earlier this year, did not return a message seeking comment, though a friend confirmed she’d received it. Christopher Huggett, who will spend his 30s in a prison cell, initially indicated he would comment for this story but later declined.

The newspaper was still sitting on the couple's kitchen table three weeks later, on Aug. 21, 2018, when Holder left his home and was pulled over by a Mesa County Sheriff's Office deputy. At the same time, a DEA agent handed Matos a search warrant, and a group of officers from two federal agencies and the sheriff's office spread through the couple's home.

Holder was brought back to the house in the deputy’s car, where he waited while agents opened drawers, closets, cabinets. From an armoire in the couple’s bedroom they took $5,000 and plastic baggies — the same plastic baggies, the agent testified, that law enforcement had previously obtained containing fentanyl. From the coffee table they took a pill cutter but no pills. From the nearby couch they found an iPad, and from Holder they took a cellphone. Both became instrumental in his prosecution.

Holder pleaded not guilty to a slew of drug charges and was denied bail. Matos would soon join him: Five months later, in early January, one of Chon’s lieutenants turned up at her work. He left nearly 2,000 pills in a potato chip bag. The bag was still in Matos’ car the next day when she was pulled over.

In the days and weeks and months that followed, the rest were arrested, too: Holder’s two children, his stepdaughter, his ex-wife, Zack Green, a couple who were old friends of Holder and several other users who sold pills to support their addictions.

All of them would take plea deals or wouldn’t be charged. Only Holder went to trial. His children testified against him. So did Matos, and Christopher Huggett, and Green. COVID-19’s emergence delayed his trial until April 2021. To protest the lack of minorities on his jury, Holder, who is Black, announced his intention to stand for the entire trial. His defense attorneys — whom he’d tried to fire shortly before the trial started — sought to undermine the credibility of those who’d testified against Holder, calling them “snitches” and “untrustworthy.” They suggested another fentanyl dealer in the area, who was arrested shortly before Holder, may have been responsible for some of the pills, and they sought to minimize Holder’s knowledge or role.

After two days of deliberation, the jury found Holder guilty on four counts related to distributing the fentanyl pills. One of those charges included the additional finding that the distribution led to the death of Jonathan Ellington. It was the first time a Colorado jury had ever convicted someone for killing another person with fentanyl pills, and it carries with it a sentence of 20 years to life in prison.

Even now, the grief still ambushes Cheryl and Dave Ellington. It’s been 4½ years since Jonathan was found in his bedroom, and his death is no longer the first thing they think about in the morning. But it’s never far behind: Sometimes the music from “Home Alone” comes on, and they remember it was his favorite movie, and they’re pulled apart again.

"You never get over it," said Cheryl. "You learn to live and take it with you."

They had seen Jonathan weeks before his death, when they'd stayed at the Hotel Jerome, ridden the gondola to the top of the mountain, sipped hot chocolate and admired their son's success. They were playing cards with some friends when it was their phone's turn to ring, three days after Christmas 2017. Dave didn't tell Cheryl after the first call. He waited until he was sure.

Cheryl and Dave are Christians, active in their church. They’re focused on remembering Jonathan as he was. They don’t want Bruce Holder to burn in hell. But they want him to spend the rest of his life in prison. They’ve participated in the court process, providing statements at Zackaria Green’s sentencing, and Christopher Huggett’s, and they’ve weathered the stutter-start movement of the justice system.

"Bruce Holder had proven in every step of his life - whenever he's faced with an opportunity to do something illegal or wrong, or deadly or whatever, he's chosen to do it," Dave said.

Prosecutors want him to get a life sentence, too. Only that, they wrote in a filing last year, “is sufficient.” Holder, who’s 56, is preparing to fight his conviction while awaiting his formal sentencing, which has been delayed twice. He’s now scheduled to appear before the judge in August.

His son, who was charged as a juvenile and served one year of probation, has relocated. As a juvenile, he is not named here. His daughter, Lexus Holder, is scheduled to be released from prison on New Year's Eve, 2023. Their mother and Holder's ex-wife, Corina, died in June 2020, after years of substance abuse.

Zackaria Green was released from prison earlier this year. Before he was arrested in 2019, he’d continued to struggle with his heroin use and had been homeless. Matos was released recently, too, after spending three years in jail and prison. Jerry Huggett said she’s been seen donating plasma in Grand Junction. Jerry’s son, Christopher, was sentenced to 14 years after pleading guilty to distributing fentanyl resulting in death, the harshest sentence yet. He’s appealing that judgment, and Jerry is adamant that his son, while guilty, has been railroaded.

Meanwhile, the fentanyl dealing and death march on in Mesa County, in Colorado and in the United States. Fentanyl-related overdoses statewide have quadrupled in three years, even as Colorado law enforcement routinely set new seizure records: More pills have been seized by Colorado law enforcement through the first six months of this year than were taken in all of 2021.

“The Bruce Holder case was the kick off to that,” Mesa County Sheriff’s Sgt. Justin Bynum said. “It opened everybody’s eyes to what it is and what we’re going to start dealing with.”

The men who supplied Holder have not stopped. Chon — Bertoldo-Nunez — has not yet been arrested, but he was indicted in August 2020, after two of his new alleged dealers were arrested in Colorado for trying to sell thousands of blue pills to a man working for the DEA. One of the indictments facing Chon is for distributing the pills that killed Daniel, D.C. and Sandy’s son.

During his time, Holder was the biggest fentanyl dealer on the Western Slope and one of the biggest in the state, law enforcement said. But he pales in comparison to what the state’s seeing now. The noticeable dip in supply after Holder was arrested, Mesa County Sheriff Todd Rowell said, “has been filled since then.”

Victor Yahn has seen all of it. He was elected county coroner in 2018, shortly after Holder was arrested, but he’s been with the coroner’s office since 2011. When he started, the opioid overdoses he handled were heroin or prescription pills. Fentanyl crept up four or five years ago, infrequent at first.

Now, it’s the primary opioid on the street, an addiction medicine provider in Grand Junction said. Contrary to the former coroner’s practices, Yahn runs drug screens on each body that comes through his doors, despite the expense, because he wants to know exactly what drugs are circulating in Mesa County.

“Our job has gotten so bad,” he said, “that in Mesa County we are hiring a victims’ services coordinator to help walk families through the process when they lose somebody traumatically through a drug overdose or from a car crash or an unexpected fatality.”

As he spoke, his computer dinged. Toxicology results from another suspected overdose had just arrived. They were positive for fentanyl.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Fentanyl in Colorado