DENVER — In Colorado and across the nation, communities of color are vaccinated for the flu at lower rates than non-Hispanic white communities. Doctors and those who work in public health attribute the disparity to layers of reasons.

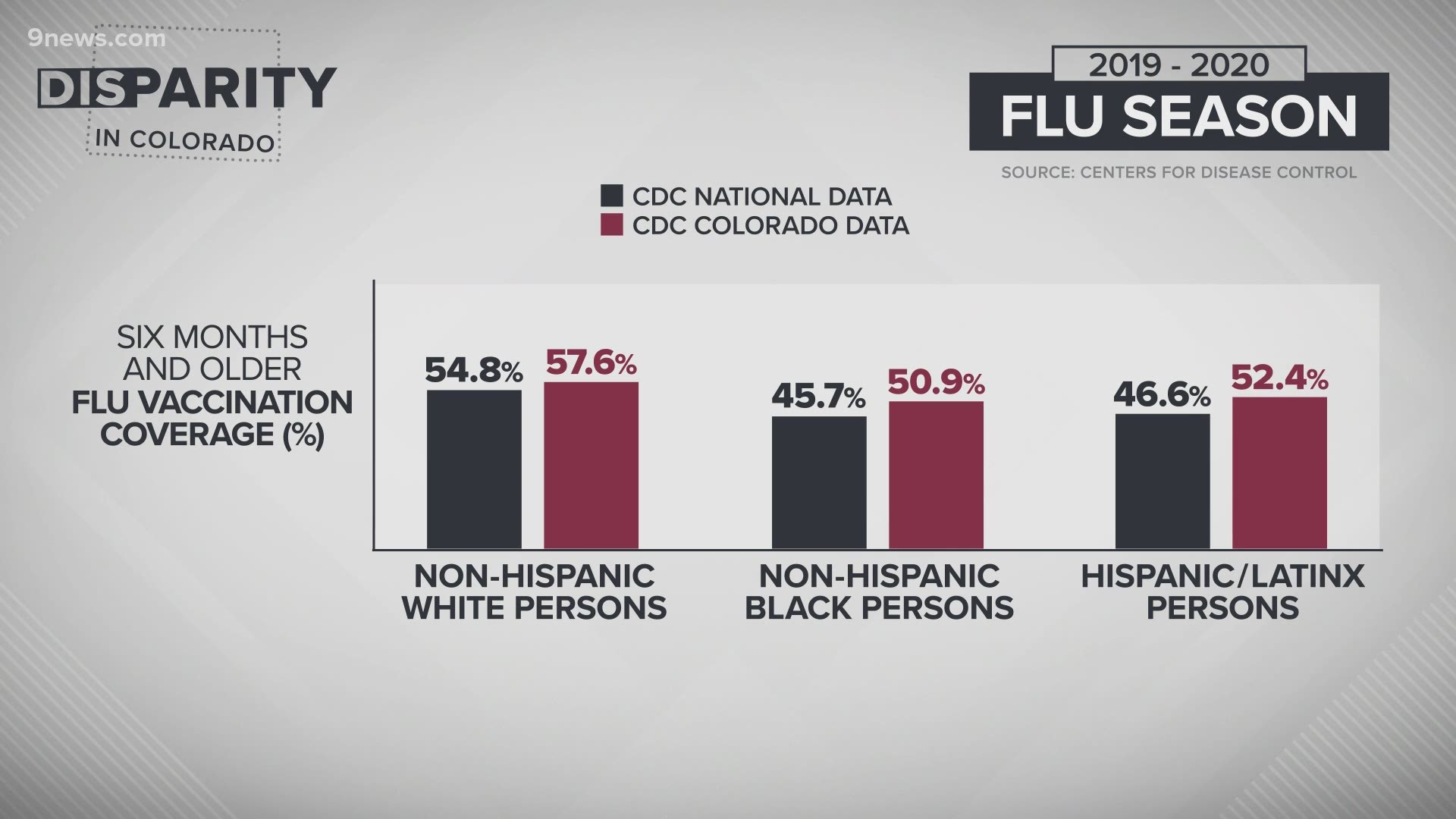

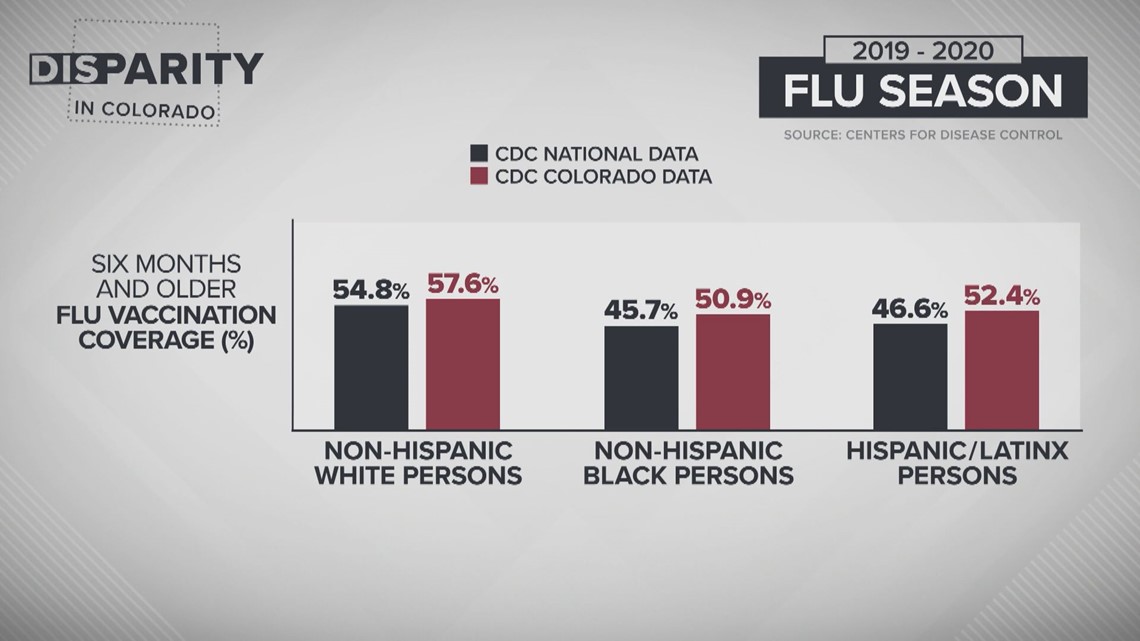

According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 54.8% of white persons six months and older were vaccinated for the flu across the United States in the 2019-2020 flu season while only 46.6% of Latinx persons and just 45.7% of Black persons got their flu shot.

In Colorado, the data reflects slightly improved numbers for the same age group last season: 57.6% of white persons, 52.4% of Latinx persons, and 50.9% of Black persons were vaccinated.

“We know there’s been long-standing health inequities and disparities that exist and this is one of them, which is the rates of flu shot by race/ethnicity in Colorado," said Dr. Eric France, chief medical officer for the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE).

The disparity is particularly concerning this year as health officials urge Americans to get their flu shot amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I think the biggest reason we've been campaigning like crazy for everybody to get their flu shots is that it can mimic the same symptoms as COVID. We also worry that it can intermix with COVID. So, you could potentially get the flu and COVID which we think would be horribly dangerous,” said Dr. Michelle Barron, director of infection control and prevention at UCHealth.

RELATED: While COVID-19 remains a top priority, the flu threatens to make matters worse in a few months

The disparity between non-Hispanic white communities and communities of color as it pertains to flu vaccination uptake rates is particularly concerning for physicians as they know the same communities are also disproportionately impacted by both COVID-19 and the flu.

A CDC analysis of the previous 10 flu seasons found non-Hispanic Black persons, non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native persons, and Latinx persons all had higher rates of hospitalization for the flu than non-Hispanic White persons.

“Many of the inequities getting brought to our attention right now aren't news to them and their communities. This is unfortunately a story that they've experienced for years or even for generations within their communities,” said Kyle Rojas Legleiter, senior director of policy advocacy for The Colorado Health Foundation.

That sentiment was reflected in a Pulse poll conducted by the Colorado Health Foundation this August.

The poll found a majority of Coloradans surveyed believe Black Coloradans are more likely to receive poor quality or inadequate healthcare. Half of respondents believe Latinx Coloradans are more likely to receive poor quality or inadequate healthcare.

The Pulse poll also found a racial difference among Coloradans willing to take a COVID-19 vaccine with one in two Black Coloradans saying they were likely to get vaccinated and two in three Hispanic or White Coloradans reporting the same.

“We know from our experience with other immunizations or other vaccines both here in Colorado and in the rest of the country that there are racial differences in who's more likely to ultimately get a vaccine or not,” Rojas Legleiter said.

There is no simple answer as to why these disparities exist but Deidre Johnson, the executive director for the Center for African American Health, would argue they aren’t bugs in the system.

“All of these disparities, whether it's flu vaccine or the COVID issues, they're all deeply rooted in systemic racism… Our system is creating exactly what it was designed to do,” Johnson said.

Of the existing disparities, Dr. France said, “we haven't built all the right systems that best meets the needs of our populations.”

We asked Dr. France, Johnson, and a handful of other physicians, public health officials, and community organizers to walk us through some of the barriers to flu vaccination that exist among communities of color.

(Editor’s note: Responses may have been edited for context and clarity)

LOGISTICAL BARRIERS

Dana Kennedy, Center for Health Progress Director of Community Partnerships: “We want to take a step back and look at the bigger picture. We think about four main reasons and really all of them are tied to racism at the core. The first being Black Indigenous people of color are less likely to have access to things like safe reliable transportation to be able to go get a vaccine. They’re also less likely to be able to have a job where they can leave during clinic hours or have paid time off to meet their health needs. Communities of color are less likely to have health care and have health coverage or support to get regular preventive care.”

Kyle Rojas Legleiter, The Colorado Health Foundation Senior Director of Policy Advocacy: “It may not be super convenient for them. To go and get a vaccine, you have to take time off work, you may have transportation barriers, you may not have a regular relationship with a primary care physician or clinician. All of that might be part of the reason why they might not get one.”

Deidre Johnson, Center for African American Health Executive Director: “It's always easier to reach people in the community that they're in. If you're working a job and can't take off or have transportation challenges, to have something close to home is even easier. It just removes the barriers and, you know, there's a whole concept of trusted community organizations.”

Dr. Michelle Barron, UCHealth Director of Infection Control and Prevention: “Access to care may be also part of the problem where normally if they had regular scheduled visits with specific people they may be more likely to do this but they may not necessarily have those relationships or access to those types of relationships.”

INFORMATION BARRIERS

Gordon Duvall, Doctor of Nursing Practice and CU Anschutz Community Research Liaison: “I’m pushing the science. It’s going to be really about education. We have to educate people, just like we do with anything else.”

Dr. Barron: “Medical literacy is really important in terms of having good information and understanding the information. If you add cultural language barriers on top of that, you can obviously have a high degree of skepticism or fear of whether this is a good idea or not. I think one of the most important things we recognize from the pediatric world is just having your physician say, ‘I think you should get this particular shot,’ has huge impact on uptake. I think just getting good information is still the key thing. I think there’s a lot of stuff out there that is bad information or potentially inaccurate. It's so easy to go down that rabbit hole.”

Johnson: “I was on a wonderful call with a gentleman who is going to help us do a virtual meeting with special experts, and he referred to a haze. Whether it's because of personal experience, what you've heard, or the Henrietta Lacks stories, the Tuskegee stories, those things that we can point to, historically, for our distrust in the system. All those things create a haze. The more information you can give to people, the more you can kind of run through it so that at least they can make a clear decision on what they want to do, not just be swept up."

HISTORICAL BARRIERS

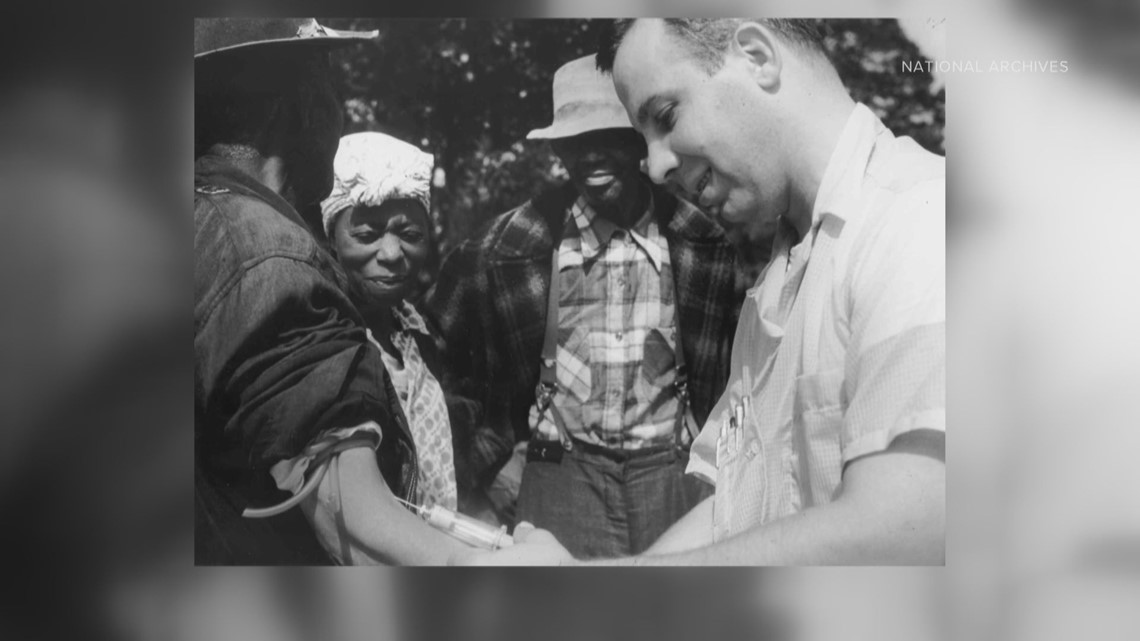

Dr. Shanta Zimmer, CU School of Medicine Professor of Medicine and Infectious Diseases and Associate Dean of Diversity and Inclusion: “It's a complicated issue. There are many layers of reasons for differences in vaccine uptake. One of the ones that gets talked about a lot is mistrust. Mistrust of the healthcare system. Mistrust due to historical wrongs and the way experimentation and research studies have been done over hundreds of years… Historically, our enrollment of minority populations into clinical trials has been very low. There have been some horrible examples of experimentation and victimization of enrollees like the Tuskegee Syphilis Study that took place in Alabama. There have also been studies like examples like Henrietta Lacks and the misuse of her own tissues and not providing proper reparations to her family members or even consent. Those are big historical examples, but then we think about social injustices, structural racism, those all contribute to a lack of trust and an anger about the way communities have been treated by major institutions like health care.”

Duvall: “It’s not like the healthcare system has a good track record of being honest or not doing things to harm these communities. As a matter of fact, they've done just the opposite. So, they have really no reason to trust. I think that’s a big aspect of it.”

Dr. Barron: “I can't imagine what that must feel like to have that sort of history and know that it happened, and I think it's something that we just have to acknowledge that yes, it has occurred. We do things very differently than we did when those things occurred. But I understand why you're skeptical and these are reasons we’d still like you to consider it again this is, he is being doing the things properly, giving them information so that they understand what may or may not be happening the risk benefits, obviously, and then continuing to work with those communities, knowing that it may still take a while to get their trust but hopefully we can get there.

Kennedy: “Medical experimentation without consent, testing vaccines on communities of color, forced sterilization of black and brown women, it all leads to that mistrust which is very well founded and understood. It also leads to our current reality where folks still face a lot of discrimination in health care, both at the individual level in interactions with the healthcare system and then the broader structures around who has access to health care, who doesn't, and why.”

WHERE TO GO FROM HERE

There is reason for optimism according to those close to the problem.

“The future of medicine is bright, for sure,” Dr. Zimmer told 9NEWS.

She and her colleagues at the CU School of Medicine are working to build a pipeline of diverse physicians “because we know that patients will accept vaccines more readily from people who look like them.”

“You can't understate how important it is to have someone who reflects you and looks like you within the system,” Deidre Johnson said.

As Johnson waits for the pipeline to develop, she is also working to address logistical and informational barriers.

At the Center for African American Health, she focuses her efforts on providing community-based care and information to cut through the ‘haze’ of misinformation.

Johnson is also encouraged by the collaboration and communication she is seeing between community health organizations like hers and public health organizations.

“As much as agencies want to do things for community, people don't want to go to agencies. They want to go to those places that are close to home where they’re used to gathering and where they have a level of trust,” Johnson said.

She sees this moment as a window of opportunity to have difficult conversations about the path forward.

“Because of COVID, we can't really look away. We can't do anything but pay attention. What are the things we can do to really change it? Because if we do nothing, the next COVID is going to come in and wreak the same havoc,” Johnson said.

Dr. Zimmer also believes the only path forward is to confront the past.

“It requires all of us acknowledging, apologizing, and making steps to move forward in the right direction,” she said.

Gordon Duvall agrees but wants to see that commitment all the way up to the highest levels of the healthcare system.

“Just like it, went to great lengths to misinform people to do the bad things it did, I think the healthcare system has to go 100 times more over the top to convince people it’s transparent and has changed,” Duvall said.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Voices of Change