DENVER — Sixteen years in real estate has taught Muriel Williams-Thompson the market is different for different people.

She knew that when she got into the business after hearing stories from her grandparent’s who sold homes seven decades ago.

“Selling homes to Black families back in the '50s was, it put your life in danger as a real estate professional,” Williams-Thompson said. “There were individuals who hated you for that. So they had a lot of death threats. Bomb threats on their home things like that. It was rough. It was rough times.”

That history compels Williams-Thompson to do better today knowing the history still impacts people of color buying homes.

“With inventory being so low right now in Colorado, you’ve got to care about something,” she said.

Williams-Thompson is the president of the Denver chapter of the National Association of Real Estate Brokers, a Black real estate group with the mission of equal housing for all.

“The racial disparities do still exist because the opportunities across history and the historical factors that have caused the disparities still exist,” she said.

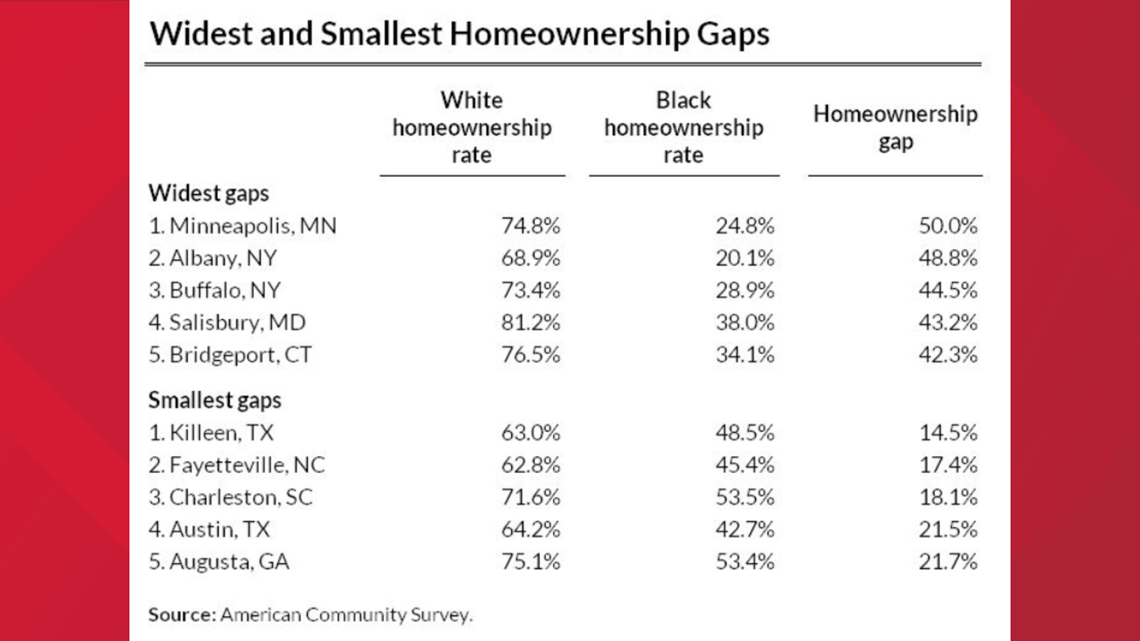

The gap in homeownership between Black and white Americans is larger now than it was 50 years ago. A 2018 study from the Urban Institute showed the Denver metro area has a gap of almost 32% between white and Black homeowners.

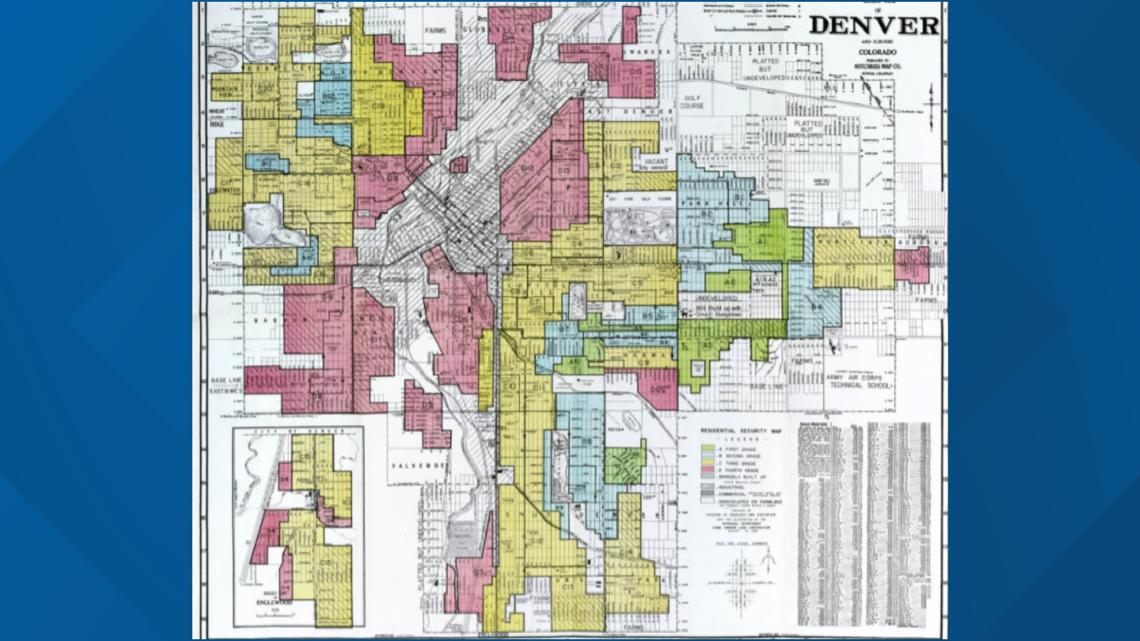

Experts point to redlining, the practice banks and other financial institutions had of declaring certain neighborhoods hazardous and not allowing people to take out loans in those areas. The neighborhoods marked red on the map below were predominantly populated by people of color in 1938.

“This has been the single most negatively impactful thing since slavery as it pertains to African Americans and even Latinos later on,” said Pheonix Jackson, the spokesperson for a blind lending platform called Achroma.

While the discriminatory practice of redlining is illegal today, Jackson said it happens in more subtle forms.

“The racial disparities in denial rates for purchase and refinance continue to stretch the wealth gap,” she said.

Not only did redlining stop Black families from accumulating wealth through buying a house, Black families continue to pay more in interest when getting a loan.

A 2018 study by the University of California, Berkeley showed Black and Latinx borrowers pay $500 million more a year in interest than white borrowers with comparable credit scores.

“It almost feels as though these extra obstacles are put in place just to stop certain homeowners,” Williams-Thompson said. “I don’t know if that’s true but it feels very much like that.”

She added the pandemic has made it even tougher because some banks have heightened their criteria for lending leaving clients no options to borrow money.

“To actually raise the criteria right in the middle of when people have finally started making some headway is just disheartening,” she said.

Disheartening, but she and Jackson are not giving up. Both believe buying homes is a chance to close that wealth gap for people of color.

>> Down payment help and information on fair housing from NAREB can be found here

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Feature stories