DENVER — There's a version of U.S. history students in K-12 classrooms are exposed to, most of which lacks perspectives from communities of color.

From a European perspective, Christopher Columbus discovered America. From an Indigenous perspective, Columbus and other European explorers stole the homelands of various Native tribes.

"The United States was a territory inhabited by Indigenous people and then there were European settlers who came, colonized, and formed a government. That’s just a fact, you can have feelings about that fact, but that is a fact, to say otherwise would not be accurate," said Dr. Jennifer Ho, an Ethnic Studies Professor at the University of Colorado Boulder.

"Individual people, as well as people connected to the U.S. government, like Thomas Jefferson, bought people from Africa, enslaved them to work on his property without any remuneration, right? That’s the system of chattel slavery. That simply happened."

Dr. Ho added that most of us do not have an accurate sense of U.S. History based solely on what we are taught in K-12 classrooms.

"It is uncomfortable to learn about these things, but it’s much better to know the truth about our history, rather than to sugar coat it and to think somehow that our children aren’t capable of digesting complex things," said Dr. Ho. She said she is often accused of being anti-American when discussing matters of race and anti-racism in America.

To that, her response is "You’re not giving the United States enough credit. You’re not giving the United States' democracy and government enough credit that if you want something to get better, you want to fix it, you want to correct the mistakes, you say here’s the way to move forward."

The Colorado Department of Education is currently in the process of reviewing and revising the state's standards for social studies classes. The Social Studies Review and Revision Committee is accepting public feedback on their drafted revisions until Feb. 1, 2022. You can learn about using the online system for providing feedback here.

Associate commissioner for student learning with the Colorado Department of Education, Melissa Colsman said they will take public feedback and present their recommendations to the board in March 2022. If approved, districts will then have two years to adopt the new standards.

"With anything in education you always want to make sure that you always have an opportunity to regularly refresh and review, make sure that the most important content that kids should be learning is reflected in those standards," said Colsman.

Learning with cultural context

Renee and Beto Millard-Chacon are raising two Indigenous and Chicano boys.

"My kids are Indigenous and I still have to teach them this is the land of the Ute, the Cheyenne, the Arapahoe and yet they're not taught that in school," said Renee.

Books in their home are filled with history they wished their kids were learning in school. One of those is "Cesar Chavez and La Causa", a picture book detailing the life of the Mexican American leader who advocated for civil rights of farm workers.

Another is "Return of the Indian" by Phillip Wearne. In his book, Wearne identifies the numbers and types of Indigenous peoples today.

"I made it a point for my children to see that when you learn about cultural identity in your education, it's transformative," said Renee.

"The unwillingness to teach our children as they grow allows them to grow into adults that ignore the problem," added Beto.

It wasn't until she was 15 herself, that Millard-Chacon learned that Kit Carson played a major role in The Long Walk of the Navajo.

She recounted when her son was taught about Kit Carson in school during a Thanksgiving lesson. At the time, her family lived in California.

"They were mentioning pioneers of the west and they mentioned Kit Carson. My son was about 4 or 5 at the time," she said.

"I actually addressed it with his teacher, and I told her the truth, that we were also part Diné, I do not feel comfortable about him learning Kit Carson in this way without any context and if she was okay involving it. And she was, she was super receptive at the time that she actually asked me to come in and talk to the class about it."

Learning how history informs the present

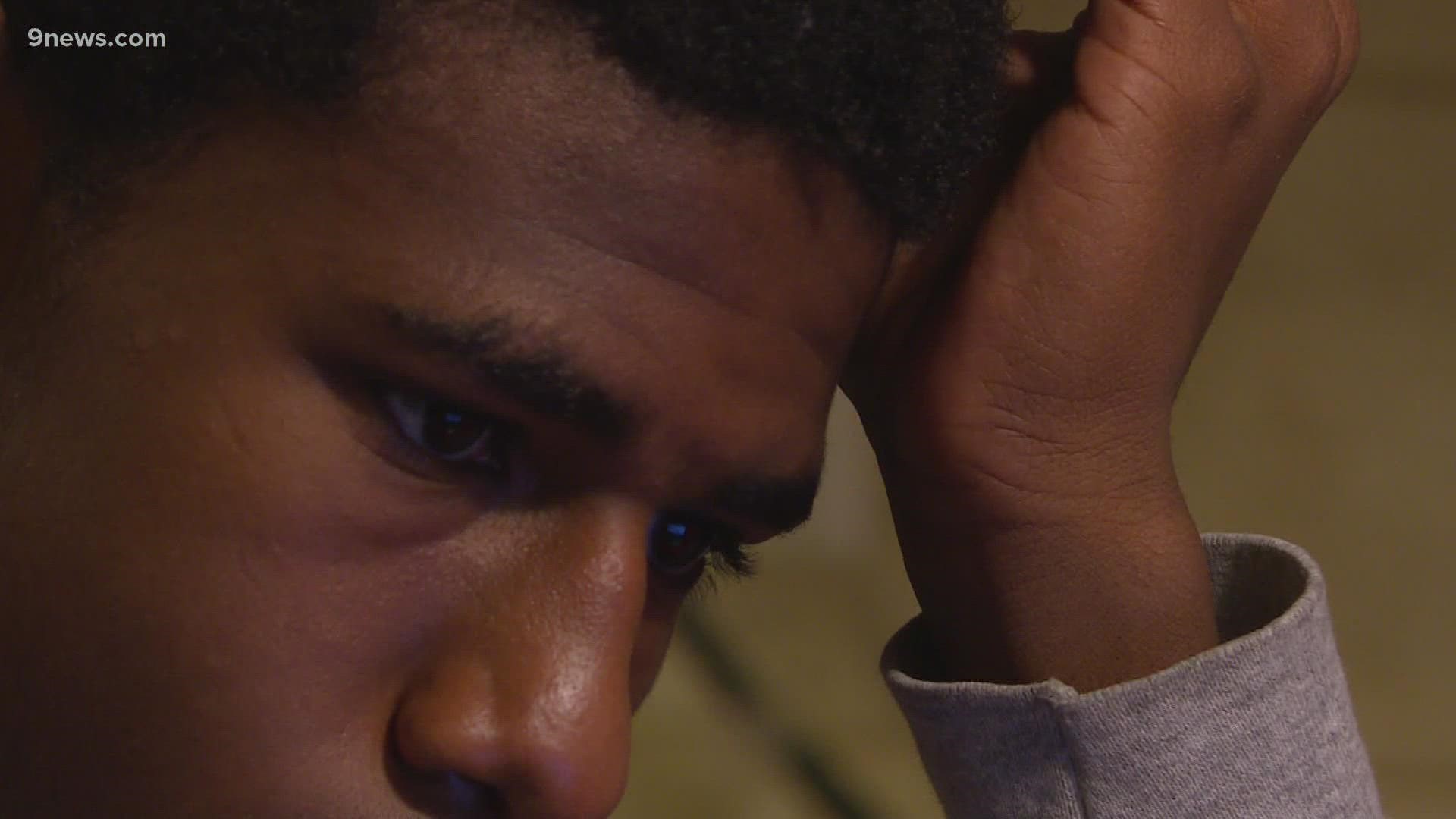

In a different home, Monica Williams knows that not everyone is used to having conversations on race.

She, however, doesn't have the option to avoid talking about race with her sons.

"Oh gosh, we've been having those conversations from elementary school," she said. "I'm teaching my kids to be advocates for themselves and also to understand that they cannot be average. They have to be better than average in order to be viewed even on equal playing ground."

Williams believes history helps inform the present and it's important for children to understand that history, too. "Because we have remnants that exist today," she said.

"I don't want them to be blind and I want them to know what systems are operating so that they're prepared to navigate them, to dismantle them, to disrupt them, I want my kids to have that," Williams said. "So I'm not gonna rely on the school system to do that, I do believe the school system has a role in it, but I'm just not relying on them to do that. That's something that as a mom, a Black mom, I try to do just naturally."

She believes understanding why inequities still exist is worth learning about.

There are reasons why there are tensions in certain communities, reasons why there's a lack of advancement in certain communities, Williams said.

"For instance, the Black community overwhelmingly has not generated the wealth and the generational wealth that maybe some white families have had the ability to generate."

"It's not pointing fingers"

Both Williams and the Millard-Chacons know that there may be a hesitancy to discuss some of these issues and histories to avoid making white students and families feel guilty about the past.

"The point of talking about it is not to make people feel guilty about the family they were born into," Williams said. "The point is to be able to get people to recognize how it still lives today, if it’s living today then that’s too far gone"

Millard-Chacon, for example, has taught her kids about the Sand Creek Massacre despite hearing some arguments that details of the event are too horrific for kids to understand.

"Yes, it’s incredibly depressing to know that two thirds women and children were killed in Sand Creek and yet it should be known and that needs to be weighed for the context that it was and how the founding of this state was truly made," Millard-Chacon said.

She and her husband do believe there are ways to teach kids about the history of communities of color in the United States in a way that is appropriate for different age groups.

Fostering cultural pride in the classroom

Beyond history, Williams wants her kids to learn about the whole story as it relates to Black American history.

"I don't want them to just know that history from a white man's perspective," said Williams. "I want them to know Black history is American history and that we have been contributors that I believe this country was built on our backs, for free, for nothing and that we have a stake in it and that we’re not outsiders and that we all have the right to be here, right, and that differences and diversity matter and that’s a strength. It’s not a deficit, it’s something that makes us stronger together."

Williams said she does not remember having conversations about Black history in her primary education. She attended an historically Black College and that's where she remembers learning more about Black history in the United States.

"I remember learning about the pilgrims and Christopher Columbus discovered America, all of those things that you grew up believing to be true until you find out later that it was painted in a way that glamorized what happened and didn’t take into account how others might have experienced things differently," Williams said.

Williams wants her children to not only embrace their heritage and their background, but to embrace the heritage of others around them. It's something she teaches at home, but believes classrooms also have room for those types of lessons.

For the Millard-Chacon's, they are intentional about fostering cultural pride in their children.

"I guess I’m tired of my children learning from a dominant narrative that doesn’t celebrate their cultures," said Renee. "I hope that kids have the ability to hone their own cultural identity now and that that’s how their ancestors even created it for them."

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Education stories from 9NEWS