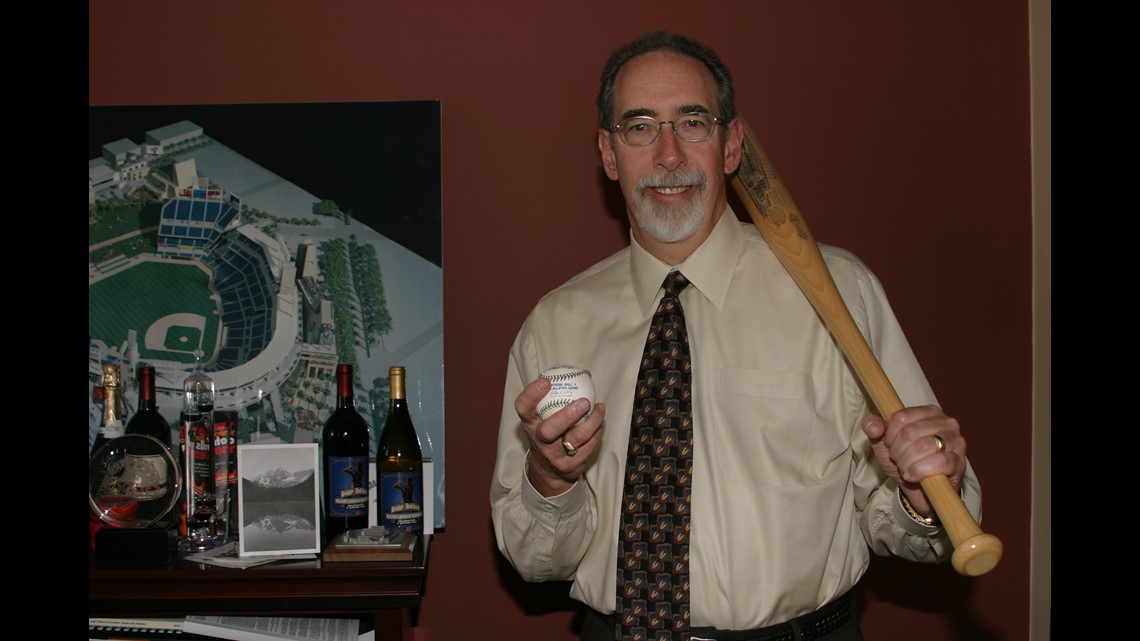

DENVER — This article was originally published in July 2016. Paul Jacobs died this week at 78. 9NEWS' Mike Klis calls him one of the founding fathers of the Colorado Rockies. Read Klis' full obituary here.

There was no ball diamond, yet, although thanks to the local fans’ insatiable craving for baseball, there was a promise to build one.

There were no players, no scouts to pick the players, and the controlling ownership group was of such a collection of flimsy financial commitment that it would soon blow up into a state of all-that-work-for-nothing peril.

Yet, thanks in no small part to the methodical and resourceful work of a Denver attorney named Paul Jacobs, National League president Bill White stepped up 25 years ago this Tuesday to the podium inside the packed Imperial Ballroom of the downtown Hyatt Regency Hotel and dramatically ended Colorado’s 32-year quest for a Major League Baseball franchise.

"I'm here to tell you that at 10:40 Mountain Daylight Time," White said on Friday morning, July 5, 1991, "you became officially a member of the National League."

The Colorado Rockies were born. Ordinarily, there is no cheering in the press box. Etiquette, schmetiquette. The ballroom -- crowded with volunteers, politicians, no longer prospective-but-identifiable ownership partners, family members and media -- erupted in applause.

Sitting well down the dais to White’s left was Jacobs, the attorney whose diligent work as the driving force for Denver’s baseball bid made this announcement possible.

“From the beginning they didn’t have enough money,” White recalled 25 years later from his Pennsylvania home along the Delaware River. “Paul put that together and helped us put together some bridge money to make up for the money they didn’t have to qualify. Paul was the only one we talked to.’’

A year later, though, Jacobs’ work was frighteningly close to going for naught. On July 29, 1992, a little more than 12 months after White proclaimed Denver as a National League franchise and the ownership group announced the team’s name as the “Colorado Rockies”, Mickey Monus walked into Jacobs’ office and stated, “We have a problem. I’m no longer acceptable to baseball.”

It was a problem all right. Monus was the No. 1 investor in Denver’s ownership group. The feds were closing in on Monus and his embezzlement and fraud scheme involving his Phar-Mor discount drug stores. He would eventually be convicted of multiple crimes and served 10 years of 19 ½-year sentence in prison.

Jacobs had been a lawyer for 24 years. He knew exactly what to do.

“Mickey,” Jacobs said, “don’t say another word.”

Monus and his longtime business partner John Antonucci, and their fathers, represented $20 million of the $21 million tied up in the Rockies’ controlling general partnership. That $20 million was mostly promised through loan documents, not cash, and was about to become locked up with Monus.

The Rockies’ first game was nine months away. Jacobs quickly came up with a plan that saved the franchise. It wasn’t a conventional strategy. But then neither was this particular crisis.

For the second time in two years, Denver baseball didn’t have an ownership group. Through some enterprising, but above-table lawyer work, Jacobs -- that very day Monus announced his problem -- got the Monus’ family to transfer $10 million in Rockies’ stock to Jacobs and then team accountant Stephen Kurtz.

Not six weeks later, Jacobs transferred the stock to Jerry McMorris, Oren Benton and Charlie Monfort, limited partners who stepped up into the controlling general partnership after the Monus fallout.

Jacobs didn’t make a dime in the transaction. What he did do was get Monus out before anyone knew what was coming. By acting so quickly, he fended off the concerns and possible action of Major League Baseball against Colorado’s still embryonic club.

“To me, in my mind, the critical element was separating the general partnership from Monus and Antonucci,’’ said Monfort, the only living member of the Rockies’ revamped general partnership group. (Benton and McMorris each eventually sold off their Rockies stock to Charlie Monfort and his brother Dick Monfort. Benton died in 2006 at age 72; McMorris was 71 when he passed away in 2012). “To me that was the most important aspect to keeping the franchise. The fans of Colorado were why we got the franchise. Paul did what he had to do to save it.”

**************

Denver’s long, often frustrating, but eventually successful pursuit of Major League Baseball was an almost daily reminder that power in this country lies with those who have money -- and their lawyers.

In that order. Money is the be-all but in the event it does vanish, you better have a good lawyer.

Jacobs did two things in bringing Denver a major-league franchise: One, he took the leadership role in coalescing the Rockies’ ownership group and establishing credibility with Major League Baseball, and two, when the big money collapsed beneath Monus’ fraud, Jacobs saved the team.

“I could not endorse those two concepts more,’’ said Bob Kheel, the National League’s lead counsel from 1990-2000. “He was absolutely central in every aspect.

“I remember he showed up on our doorstep unexpectedly (at the National League’s New York offices) and he said, “Guess what? I own the team.’ It was that fast and that unexpected. He was good natured about it because everybody knew he couldn’t come up with $20 million.

“He is just a wonderful man, a wonderful citizen because he was doing it as a stakeholder for the city.”

Denver’s first bid for a major-league team came in 1959 when Bob Howsam, owner of the Triple-A Denver Bears, partnered with former baseball executive great Branch Rickey to form a third major league called the Continental League. MLB swallowed up that proposal by agreeing to expand its 16-team entity.

Between 1961 and 1977, MLB would add 10 teams through expansion, but none were placed in the Rocky Mountain Region.

For the 12 years between 1977 and 1989, baseball was content to hold its membership to 26 teams. Finally, a congressional group headed by then-Colorado Senator Tim Wirth pressured the major leagues to expand again.

MLB demonstrated its reluctance through its expansion fee -- it would cost the two new teams $95 million each for the right to play in 1993, or 13.6 times more than the $7 million Toronto and Seattle paid in 1977. Another $20 million to $30 million was the projected need for start-up costs.

Still, Denver had been the boy chasing the girl for too long. If a fur coat and diamonds were what it took to get the girl, then a fur coat and diamonds it would be. Figure out how to pay for it later.

A Colorado Baseball Commission was formed and successfully placed a .1 percent sales tax on an Aug. 14, 1990 ballot for the purpose of funding the construction of ballpark if Denver landed an expansion franchise.

It turned out to be the most significant sales tax in Denver sports history as that .1 percent not only funded what is now Coors Field, but Denver Broncos’ owner Pat Bowlen successfully piggybacked on that tax in 1998 to build what is now (and soon-to-be-renamed) Sports Authority Field at Mile High.

Denver’s baseball bid in 1990 had the promise of a new ballpark thanks to a 54 percent voter approval of Denver’s six-county metropolitan tax payers.

What Denver didn’t have was one dull penny in its ownership group.

For years the presumed owner was John Dikeou, a commercial real estate developer who also owned the Triple-A Denver Zephyrs. A month before the stadium vote, though, Dikeou dropped out as the Denver commercial real estate market had tanked.

Without Dikeou, Colorado scrambled. Gov. Roy Romer took control and three days after the ballpark initiative passed, he sent out word of a cold-call meeting of potential big-baseball investors at the Westin Hotel on Aug. 17.

Jacobs had called Steve Ehrhart, a Colorado College graduate who had been president of the Memphis Showboats in the United States Football League. Jacobs had previously represented Ehrhart in employment matters.

“I called him and said, “Steve, we’re going to have an opportunity here. Who do we know? How do we find an owner?” Jacobs said.

Ehrhart first came up with Mike Nicklaus, a baseball nut who had just sold his elevator company and owned the Double-A minor-league Memphis Chicks.

In a large Westin Hotel suite, the furniture was moved around and one by one, a group of big shots gathered. There were people there representing groups they said included former baseball players Doug DeCinces, Hank Aguirre, Reggie Jackson and Ernie Banks.

“There was a guy from Florida, white shoes, who represented John Henry,’’ Jacobs said.

Looking back, Henry was probably the most qualified owner in the room. He is now the successful principal owner of the Boston Red Sox, but 26 years ago, Henry didn’t take Romer’s authority seriously, while Jacobs was focused on finding local ownership.

“The Denver guys all had other businesses and if they failed in securing a baseball team, they didn’t want it to affect their businesses,” Jacobs said. “The governor went around the room and the Denver people said, “I would be willing to make a civic contribution,’ but nobody wanted to take the lead.

“I remember kicking Steve under the table and saying, “Steve, there’s nobody here (willing to take control). We can take control of this process.”

The governor asked each potential investor to submit a written proposal by their next meeting, six days later.

Jacobs convinced Nicklaus to put up a $100,000 non-refundable application fee that was placed in his firm’s trust account.

When the second meeting convened at the Westin on Aug. 23, 1990, Romer knew Jacobs’ group was the only one to present its proposal in writing. It was Jacobs who wrote it, of course.

The governor went around the room, asking again for commitments, but instead got more rhetoric and qualified pledges. Romer called for a recess. He then grabbed Jacobs and pulled him into the suite’s kitchen area.

“He said, ‘Look Paul, I’m the Governor of Colorado,” Jacobs recalled. “’I have no business doing what I’m doing. As much as I’d like to see this happen, I can’t take on this job. You submitted a letter. Do you have the $100,000?’’’

Jacobs said he did. The application with the six-figure fee was due to the National League in 12 days.

Romer told Jacobs he was going to return to the meeting and announce he was appointing the Jacobs’ group to head Denver’s application for a major-league franchise.

“And then I’m going to get the hell out of here,” Romer told Jacobs.

Romer made his announcement. And exited the room.

“The place went berserk,” Jacobs said. “All of those people who had not said a word to date, now were saying: ‘Well, wait a minute, how come you appointed him? I can do the same thing.” It was chaos.”

Jacobs stiffened his shoulders, walked to the head of the table.

“If anybody’s really interested, come to my office tomorrow morning at 9 o’clock,’’ Jacobs announced. “And we’ll talk about how we put this group together.’’

******************

Paul Jacobs grew up in the Boston suburb of Natick, where he rooted passionately for the Red Sox and Celtics, not that there were any other options in the area. He was 19 years old when he graduated from Tufts University in Boston and was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Air Force. He was later assigned to Lowry Air Force Base.

It was 1960 and he was 20. He got out of the Air Force in 1963, and got a job at The First National Bank of Denver. At night he worked toward his law degree from the University Of Denver College Of Law.

Upon graduating in 1968, he landed with the Denver law firm Holme Roberts & Owen, where he began specializing in real estate and corporate business.

“It was rewarding work,’’ he said. “Significant work. Not glamorous work.’’

In the mid-1980s, he started working with the Denver Nuggets, who were transitioning owners from Red McCombs to Sydney Schlenker, on a massive renovation of McNichols Sports Arena. That led Jacobs’ transition to sports law when local taxpayers approved the sales tax for what is now Coors Field.

Once he got the nod from the Romer, Denver’s ownership group went through one financial impediment after another. Nicklaus eventually had to bow out, leading Ehrhart to reel in the “Drugstore Cowboys,” as Denver Post columnist Woody Paige would dub Monus and Antonucci.

“We literally started dialing for dollars,” Jacobs said.

From the get-go, McMorris was in as a limited partner. He quickly recruited Charlie Monfort.

“He came up to recruit my dad,’’ Monfort said. “My dad said he’s too old, he doesn’t have an interest. But he said I have two sons. One of them is pretty bright and conservative, he’ll tell you no. And the other one is crazy and probably will. He was spot on.”

Throughout the process, the NL expansion committee wanted Denver to become one of its two new franchises.

“I played in Denver (in 1954 as member of the visiting Sioux City, Iowa Class A Western League team) and I knew how well those people attended baseball games,” White said. “Plus the National League – we were adversaries with the American League at the time – we wanted that whole Rocky Mountain region from the Mississippi up to Montana. That was a great thing for us. We all said Denver makes sense from a geographical standpoint. We told Paul, you’ve got to go get the money. We never told Paul of our preference for Denver. We never told anybody.’’

A major tipping point came when Peter Coors agreed to put $30 million into the deal from his Coors Brewing Company with $15 million going to the ballpark naming rights. If there’s one regret, it was giving Coors the naming rights “in perpetuity.” Which means the Rockies have long stopped receiving naming rights revenue to put back into the ballpark, which, 21 years since its opening, is starting to incur some major capital repair bills.

“My answer to that is, how many naming rights deals had been done at the time?’’ Jacobs said. “In retrospect, the ‘’in perpetuity’’ commitment was something we probably shouldn’t have done. But I was focused on getting the team deal done. It turned out to be a helluva deal for Coors. But, we got it done. Coors coming in was very important to the effort.’’

There were 10 cities which submitted expansion franchise bids. Miami had one locked up during the initial presentation in New York when Wayne Huizenga pulled out his checkbook and offered to pay the $95 million expansion fee right there.

Denver had to beat out eight other cities vying for the second expansion franchise, a group that included Tampa-St. Petersburg, Orlando, Buffalo, Phoenix and Washington D.C.

When the expansion committee visited the six finalists, Jacobs thought of everything for its trip to Denver on March 26, 1991.

“We landed the helicopters at Mile High, remember that?’’ Jacobs said. “And we’re standing on the mound. It was a beautiful day. A gorgeous day. At Mile High, I was nervous about every freakin’ detail.

“One of the things I was worried about was the short left field fence at Mile High. It was like 312, 315. So I repainted the number to 330. I added 15 feet.

“So I’m standing there and Bill White pulls me over and says, “Did I ever tell you I played here?” I said, ‘no, didn’t know that.’ He points out to the number and says, “Not 330.’’ I said what are you talking about?’ He said, “You know what I’m talking about.” He had me cold. Things like that happened.”

*********************

Even after structuring Denver’s ownership group and organizing the visits by Denver to the expansion committee in New York in September, 1990, and the committee’s visit to Denver in March, 1991, Jacobs still only had roughly $75 million in committed equity. Besides needing another $20 million to cover the expansion fee, Colorado’s baseball team would need money to hire employees and have them work in offices for two years prior to the team generating any significant revenue. Even if the Rockies were to start out operating on the cheap with an $8.829 million payroll that would rank 28th in the 28-team major leagues to start the 1993 season, it was still $8.829 million not covered by the ownership group.

Soon after the expansion committee were ushered back to their respective homes, in late-June 1991, Jacobs, Kurtz and Antonucci walked unannounced into the famous 9 West 57th Street building in downtown Manhattan.

They walked into J.P. Morgan offices to see about a loan. They were escorted into the office of Scott Nycum, who was in charge of any business conducted outside of where J.P. Morgan had offices in New York, Florida and California.

Nycum listened to the Colorado trio’s pitch and brought in Ken Dale, an experienced analyst who had recently worked on Eli Jacobs’ purchase of the Baltimore Orioles from the estate of the late Edward Bennett Williams, and would later handle the estate sale of the late Ewing Kauffman’s Kansas City Royals.

“Paul presented the deal and Ken looked at the numbers (projected revenues, attendance, estimated expenses) and said these are pretty reasonable,” Nycum said. “And I said, ‘Are you going to give the usual big haircut to the numbers?’ Which banks always do. And he said, “No, maybe a trim here and there, but these look pretty realistic.

“So I asked Paul and Steve if instead of going back to Denver, they could spend the weekend. Within a week, less than a week from when they walked in right off the street, we made a commitment of $40 million. It was in large part because of the credibility very quickly we felt Paul and Steve had and the numbers looked good.

“And I did some due diligence on Antonucci and Monus. Antonucci checked out OK, and I was going to look into Monus and I called up an investment banker who was responsible for the Phar-Mor relationship that had just started. And I said, ‘Do you know anything about Monus, because I have to do some background checking?’ And he said, “Oh yeah, we just checked into him, he’s fine. He just met our chairman and CEO. So he’s good.’’’

Monus was not good. Fast forward to July 31, 1992 when the Monus scandal broke. Not only was the Monus’ $10 million worth nothing, but eventually so was the $10 million promised by the Antonuccis because the Monus and Antonucci investment turned out to be inextricably tied.

“I’ll never forget the day I got up early, had a cup of coffee and was reading the newspaper and in the business section the headline read: ‘Monus indicted for embezzlement,’’’ Nycum said. “And at J.P. Morgan you can make a mistake but you cannot make a mistake on the character of the people you’re doing business with.’’’

J.P. Morgan did not panic, nor did Major League Baseball. Jacobs and Kurtz paid $10,000 to Monus and his father with the promise to pay another $19.9 million in 90 days.

“Except I didn’t have $19.9 million dollars,’’ Jacobs said. “Small problem there.’’

Denver cable magnate Bill Daniels nearly came in to buy up the $20 million but at the time he was involved in another major financial transaction. Jacobs arranged for McMorris, Benton and Charlie Monfort to purchase the Monus-Antonucci stock.

“I do remember how instrumental Paul was in smoothing over the changeover between the Youngstown boys, when they were pulling out, and our partnership,’’ Monfort said. “I remember sitting in a meeting with Monus and Antonucci about 3 or 4 in the morning and they were trying to get more money for their shares. They were wanting two bucks on the dollar.’’

The Monus’ and Antonuccis wanted $38 million for their $20 million. One reason, perhaps, was they were paying vulture-interest rates on a loan for that $20 million.

“It was crazy because they held it for not even a year,” Monfort said. “I remember saying, ‘You guys can go, you know what -- I grew up around meat packing company, I can cuss with the best of them. I remember Paul was the cooler head that prevailed and got it done.”

Jacobs wound up staying with the Rockies through their first two seasons at Mile High Stadium. During that time he crafted every major business agreement for the team, from concessions, TV, the spring-training site in Tucson, Ariz. and sponsorships, to name a few.

He put together the Coors Field lease that was considered an unprecedented “sweetheart’’ arrangement that was copied by nearly all sports franchises which have since moved into new venues.

He moved on to help the city of San Diego through its project that became Petco Park, home of the San Diego Padres; the city of Sacramento with its new basketball arena for the NBA Kings that will open in 2017; and the Wisconsin Center District, which will own the arena where the NBA Milwaukee Bucks will play in 2018.

Jacobs beat the odds again this month when he celebrated his 76th birthday. Five years ago this month, he was diagnosed with leukemia. He went through chemotherapy but because the diagnosis was still iffy, he underwent a stem cell transplant on Oct. 22, 2013.

“And I’m clean,” he said.

He met his wife Carole on a blind date while he was in the Air Force. They have been married 54 years, raised four kids, Steven, Cheryl, David and Craig, and are enjoying eight grandchildren. Jacobs is still practicing with the Husch Blackwell firm in Denver.

He closely follows the Rockies, the franchise he first helped build, then saved.

“I liked working with Paul from a business point of view because he was the kind of attorney who negotiated to get to ‘yes,’’’ Nycum said. “So it was a win-win. As opposed to some of the others where they have to get a deal where they win and the other guy has to lose. I’m a win-win relationship sort of a person.’’

Nycum moved to the Denver in August, 2001 when J.P. Morgan opened a private bank here. He retired two years ago and still talks regularly with Jacobs. He’s not the only one from those formative days who still considers Jacobs a friend.

“I probably talk to Paul more than anybody I worked with in baseball over the years,’’ said White, who is 82 and long retired from baseball.

In March, Forbes listed the Rockies’ franchise value at $860 million.