DENVER – Nine years into Denver's 10-Year Plan to End Homelessness, a visit to the city's Ballpark neighborhood suggests the plan will never live up to its name.

Years ago, the busiest shelter in the area could handle the crowds. These days, it sends a few hundred people a month elsewhere. Crime, once centered within a small park, has now spread out into the surrounding streets, angering many of the neighborhood's new residents.

Open-air drug deals take place seven nights a week, during warm or bitterly cold days.

A police officer who has worked with the homeless since 2007 says she can't recall a time when she's ever seen this many people trying to carve out a living on the streets.

At the request of neighbors, 9Wants to Know started visiting the neighborhood in September. What we found is a quickly developing area close to Coors Field struggling now more than ever to coexist with the homeless in an area historically devoted to the city's transient population.

Blocks away from the Denver Rescue Mission, Donovan, 22, and his buddy cheer when a stranger offers them the final slices of a pizza.

There's a code to life on the streets around here, they say, yet not everyone lives up to it.

"We have to gather up in a group. There's safety in numbers," Donovan said.

A few weeks ago, they met an older woman named Yoko. Yoko quickly found the two endearing.

"I don't like the shelters anymore," Yoko said.

As long as there have been shelters in the area, there have been homeless, but it's hard to find anyone in the area willing to suggest the numbers are getting better.

9Wants to Know analyzed the numbers from yearly point-in-time reports that track the total number of homeless on a given night. While homeless counts are notorious for being inexact, the point-in-time reports represent the best barometer the area has to track trends.

Our analysis suggests in three key areas – number of homeless in the metro area, number of chronically homeless in Denver, and number of chronically homeless in the metro area – show the numbers have actually gone up since the start of the 10-Year Plan to End Homelessness in 2005.

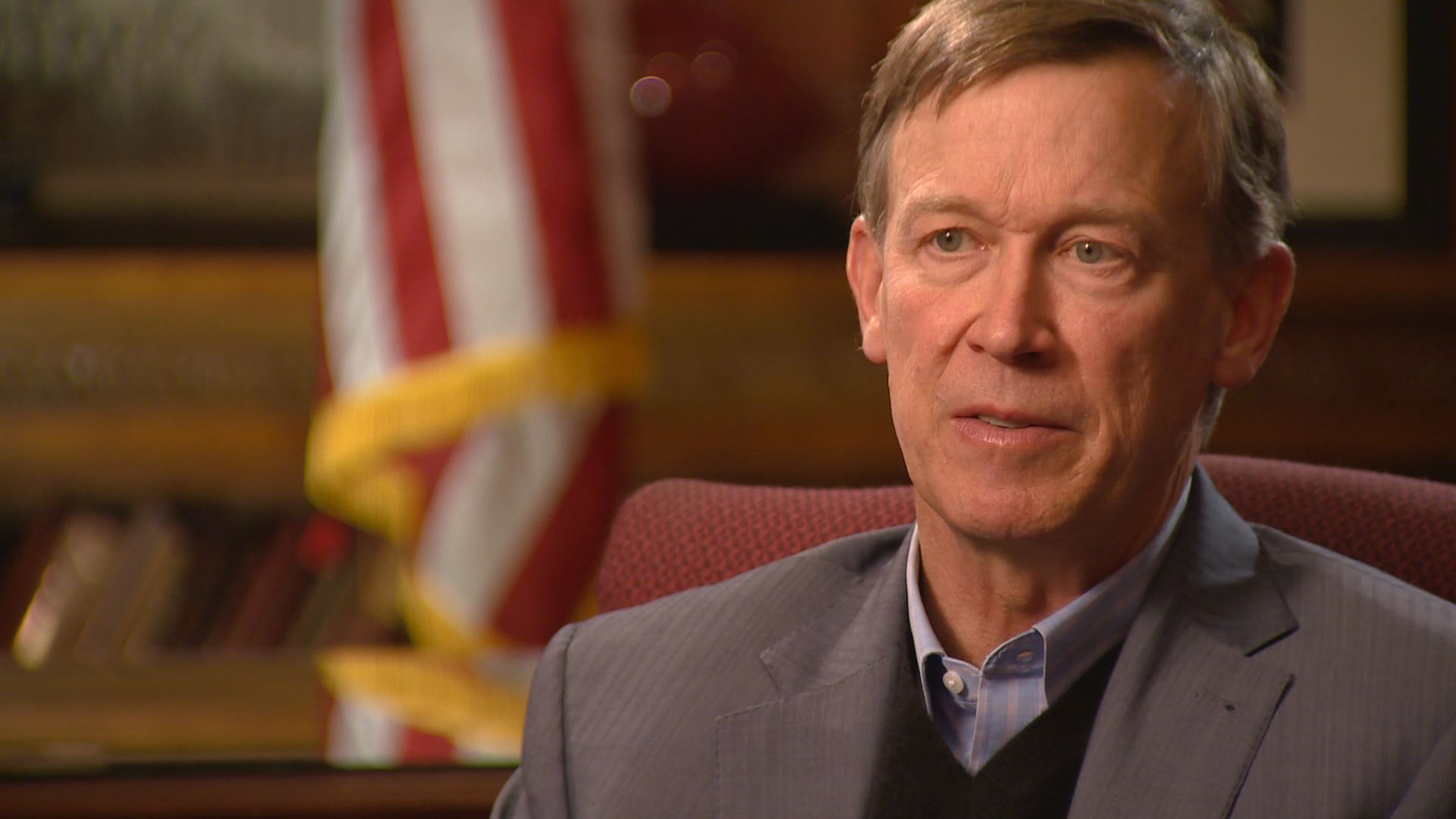

Governor John Hickenlooper was one of the most vocal supporters of the plan when he was mayor of Denver in 2005. During an interview with 9Wants to Know, he told investigative reporter Chris Vanderveen the economy is mostly to blame for the plan's poor showing.

"I think what clobbered us was the economy," he said. "To try to say where we are now – after going through a recession like that – invalidates what we did, I think, is an unfair comparison."

Starting in late July, an eight-member team with the Denver Police Department started working the streets of downtown in an effort to alleviate the concerns and complaints of the people living and working in the area.

Sgt. Layla DeStaffany, an Air Force Academy graduate, heads the team. She started working with the city's homeless in 2007.

"It just seems as if there's a lot more people out here. There's a lot youth out here in particular," she said on a recent cold and rainy night.

She wondered if it could be tied to marijuana legalization, but she couldn't say for certain.

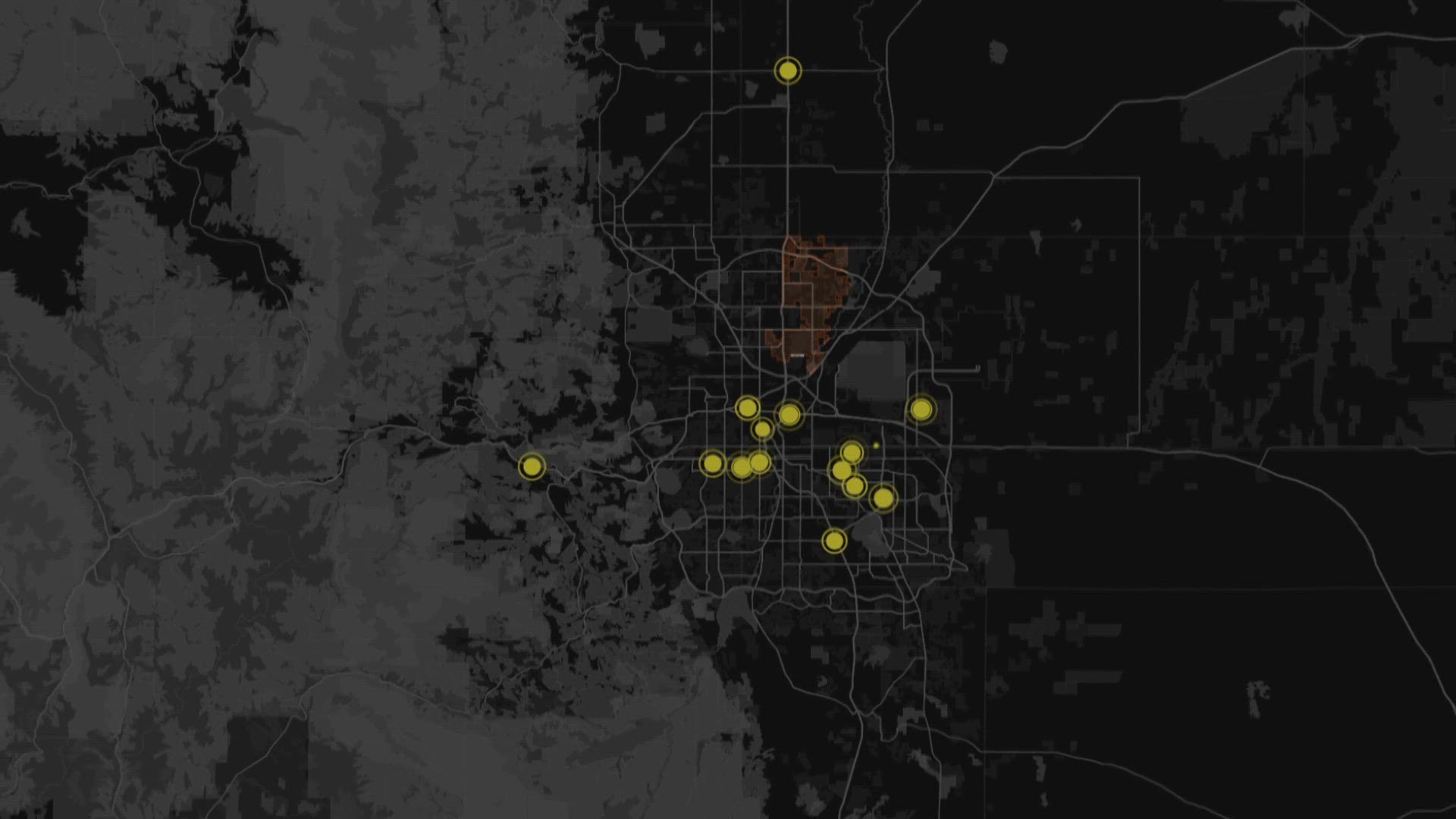

One thing that's clear to her, there's a continuing problem with other drugs in the area. The crack dealers work a section of Curtis Street on a consistent basis. 9Wants to Know tracked their selling for months. Sgt. DeStaffany said it's difficult to make arrests of the small-time dealers because officers (or a witness) have to see the transaction and then, shortly thereafter, the drug has to be confiscated.

Nearby Triangle Park sits right next to the Denver Rescue Mission. For the first nine months of the year it remained closed off and under construction. The closure of the historically troublesome park, according to Denver Police crime data, didn't bring an end to the crime. Instead, it sent crime typically seen in the park into the surrounding streets

Neighbors are fed up.

"There's a much more dangerous element to it," said one resident who didn't want to be identified.

Business owners repeatedly told 9Wants to Know they worry about the crime in the area. Many said the most worrisome element travels in almost nomadic style, hopscotching from corner to corner whenever another police sweep goes down.

The much-talked about "camping ban" has enabled police officers to openly encourage if not downright force homeless to "move along," but a much feared legal crackdown has yet to materialize. Between June 2012 and July 2014, DPD officers had only written one ticket for illegal camping.

Sgt. DeStaffany said her goal is to encourage people to use the services in the area that are available to them.

"I think you have to have realistic expectations of what success looks like," she said.

Shortly after, she offered to drive a woman to a nearby shelter.

Ten years ago, then-Mayor John Hickenlooper helped spearhead a plan to end chronic homelessness in Denver by 2015. It was an audacious plan that first originated within George W. Bush's administration. Between 2002 and 2006, numerous cities in the United States signed off on the same plan.

No one now believes homelessness will end in Colorado next year. Even the head of the group responsible for implementing the plan says the plan's most important goal will never be realized.

"I think it's clear that's not going to happen," Denver's Road Home Executive Director Bennie Milliner said. "Jesus said, 'the poor you'd have with you always,' and I'm not in a position to argue with Him."

"What we know now, we probably would have nuanced that tagline a little bit," he replied.

Homeless advocate Randle Loeb signed his name to the plan in 2005.

"Naming it the 10-Year Plan was a bad thing," he said. "One of the things about a 10-Year Plan is that by the time the 10 years are up, the person who was first responsible for it is out of office."

These days, Loeb spend much of his time talking to people most people wouldn't consider talking to. He was once homeless himself.

"If it hadn't been for the treatment and the support I received when I did, I'd be dead. You wouldn't be talking to me," Loeb said.

One thing that continues to evoke uncertainty is the governor's continued suggestion that the city was able to reduce chronic homelessness by 75 percent within the first five years of the plan. That was another stated goal of the 10-Year Plan.

9Wants To Know asked Denver City Council Member Charlie Brown if it was possible.

"No, no, I don't believe it," Brown said.

The methodology used by the City of Denver as well as the governor's office to suggest the decrease appears, at the very least, curious. In 2010, Denver's Road Home suggested the dip in a halfway report by stating there were approximately 942 chronically homeless in Denver in 2005.

But 9Wants To Know analysis of previous homeless counts shows the number to be far lower that year, the first year of the plan. Other counts show a starting point of approximately 479.

It means little on its own, but when compared with latter counts, the smaller starting point shows the city's chronically homeless numbers dipped only slightly over the years. It's also important to note the number of chronically homeless has since gone back up, well above the 479 figure.

Denver's City Auditor, Dennis Gallagher, told 9Wants to Know he would analyze our findings during his ongoing audit of Denver's Road Home. Anecdotally, he said, the numbers appear stagnant at best.

"I've got to tell you, the numbers don't look like they're going down at all," Gallagher said.

If demand on the shelters in the Ballpark neighborhood tell us anything, he may, in fact, be right.

At the Denver Rescue Mission, the staff now routinely serves double the amount of people than it did in 2005. Capacity has increased since then, but these days the Mission now routinely has to refer hundreds of homeless a month to other shelters. Before 2011, that never consistently happened.

At St. Francis, they now serve more than 30 percent more people a day than they did in 2008.

Robert is in his 60s. He'll tell you he's spent more nights out in the cold than he could ever possibly count. He's got a scar on his chest from a knife fight years ago.

"I didn't even know them," he said. I had no clue who they were. They thought I had a wallet or money."

Even still, he says, most of the people he meets out here on the streets aren't dangerous.

He had clearly been drinking. A half-empty beer can rested next to his slumped body on a chair located next to the only permanent memorial to Denver's homeless on Stout Street.

"I've slept here I don't know how many times," he said.

Vanderveen asked him how Denver's 10-Year Plan to End Homelessness is going.

Robert laughed for a moment and then said, "It's never going to happen."

At that moment he got up, threw the beer can toward a wall, and shuffled off to his next stop for the night .

He passed by a group of three more homeless less than a block away.

(KUSA-TV © 2014 Multimedia Holdings Corporation)