DOTSERO, Colo. — The deadliest volcanic eruption in U.S. history took place 40 years ago in Washington state.

It was shortly after 8:30 a.m. on May 18, 1980 when Mount St. Helens erupted.

Over a period of two months, there were more than 2,800 earthquakes recorded at Mount St. Helens before the May 18 blast, which caused a volcanic bulge to landslide down the mountain, reducing the mountain's height by 1,314 feet.

The eruption killed 57 people, as well as an estimated 7,000 big game animals – such as deer, elk and bears. Birds and small mammals also died.

That massive explosion of ash, rock and hot gasses has many asking about whether such a volcanic eruption could occur in Colorado.

THE QUESTION

Does Colorado have an active volcano?

THE ANSWER

Yes.

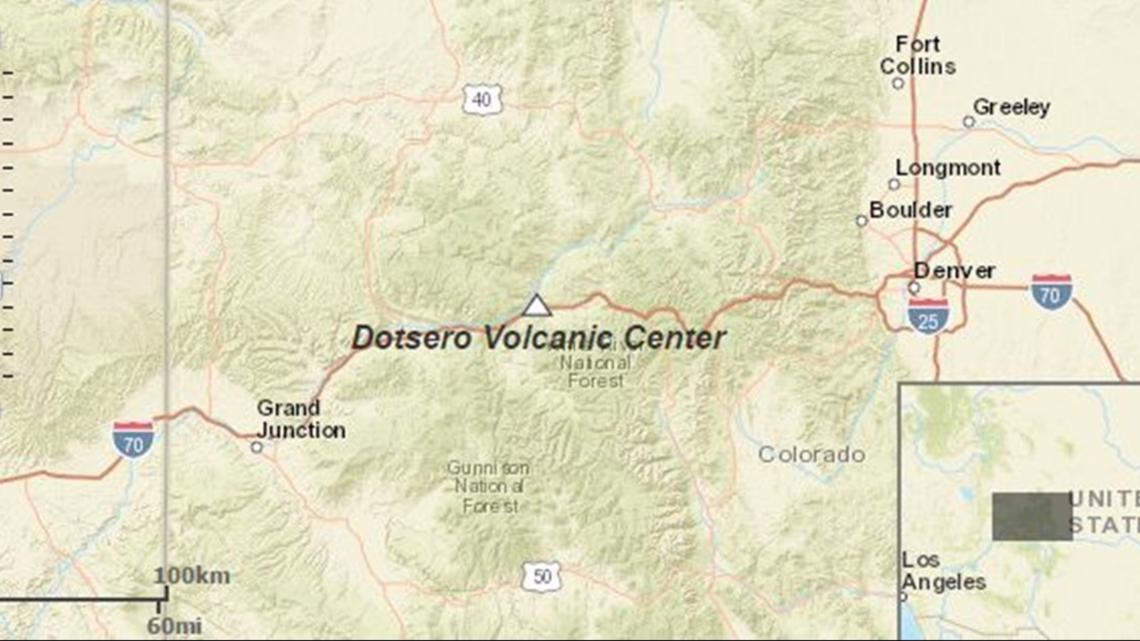

The Dotsero volcano, in western Eagle County, is Colorado’s only active volcano.

The volcano last erupted 4,200 years ago, but a 2018 report from the United States Geological Survey lists it as a moderate threat to human activity.

But is it really an active volcano? It depends on how exactly you define “active” – but you definitely don’t have to worry about dodging lava on Interstate 70 anytime soon.

Richard Busch with the Denver Museum of Nature & Science (DMNS) said the Dotsero Crater’s close proximity to I-70 and air traffic routes could be the reason it is listed as number 82 on the list, in the moderate threat category.

The USGS defines an active volcano as anything that has erupted in the last 10,000 years. In geologic time that’s not very long, but to humans, it might seem odd to say something that has been inactive for 9,999 years is active.

Dr. James Hagadorn, curator of geology for DMNS, said calling the Dotsero volcano active is very much an exaggeration.

“Is there lava spewing out of it right now?” said Hagadorn. “An active volcano is Hawaii...you can see magma coming out as lava on the surface. You can see ash coming out. It’s like Mount St. Helens.

“Dotsero is no more an active volcano than is the volcano that produced North and South Table Mountain [in Golden].”

Busch said that Dotsero has erupted twice that we know of. The last time was about the time the Great Pyramids were being built in Egypt. He also said there were Native American people in the area at the time.

Meanwhile, Dr. Christian Shorey, assistant department head of geology and geology engineering at the Colorado School of Mines, said scientists technically define an active volcano as one that has erupted in the last 10,000 years – meaning the Dotsero volcano fits the bill.

Is Dotsero likely to erupt again?

It’s highly unlikely, Hagadorn, Shorey and Busch agreed.

“Probably not in our lifetime,” Busch said. “Probably not in our kids' lifetime. I’m not holding my breath.”

Busch said most of Colorado’s volcanic activity ceased about 27 million to 30 million years ago.

And while Shorey said the magma-source for the Dotsero volcano feeds the hot springs in Glenwood Springs, he said it’s losing heat.

“The term ‘active’ is a little misleading to the public – anything that has erupted in 10,000 years is technically active,” Shorey said. “On the west coast of the U.S., that is much more the case. You’d be a lot more concerned there. Here in the Rocky Mountains, our sources kind of died, ending before the dinosaurs went extinct.”

Hagadorn said drawing conclusions just from the fact the Dotsero volcano has erupted fairly recently is just extrapolation.

“If you buy 100 lottery tickets a week, your probability of winning the lottery might be different from just buying one ticket a week … the element of randomness … [you] can’t quite apply that to an ancient volcanic deposit,” Hagadorn said.

He said it would be like saying if there is an average of one out of 100,000 people per year who are injured by a car, it doesn’t mean if you drive your car 100,000 times in a lifetime you’ll be injured once – there are more factors at play, such as how bad of a driver you are or where in the country you do most of your driving.

“Would you take information about volcanic deposits from the entire Earth and apply it to something that can be here?” he asked. “There are 100 different kinds of airplanes. You wouldn’t lump all those together, would you?”

Shinny specs embedded in some of the volcanic rocks near the Colorado site are nicknamed Dotsero Diamonds.

“Before you go running out there to grab diamonds – they’re not diamonds,” Busch said. “They are little pieces of quartz that were picked up by the lava as it moved across the landscape. The heat of the basalt affected the outside rim of these quartz crystals, so they have a little rind on them. Most are very tiny, but there are some that can be quarter size, or half dollar size.”

How does Dotsero compare to Yellowstone?

The experts say folks in Colorado should probably worry more about the Yellowstone supervolcano than the “active” one in our own backyard.

“The Yellowstone thing is a place where we wonder when it’s going to happen again – we don’t really question ‘if,’” Shorey said. “Yellowstone’s a much bigger beast... and when it blows, it can form ash that could come to Austin, Texas, all the way to Iowa if it occurs. It would definitely be civilization-altering.”

Granted, you’ve probably heard of the Yellowstone volcano. But what makes people want to talk about the Dotsero volcano is the fact that geological activity like this isn’t something folks necessarily associate with the Centennial State.

One of them is the San Juan Volcanic Field in southwest Colorado. One of its eruptions has expelled nearly 5,000 times the amount of material produced by Mount St. Helens. In fact, Hagadorn said that this was enough to cover the state with a six-inch-thick blanket of hot ash.

Closer to Denver are North and South Table Mountains, which were formed by a volcano northwest of Golden. This city – much like parts of Boulder and Jefferson County – wouldn’t look the same without volcanoes.

And why is it important to talk about Colorado’s volcanoes in the first place? The answer is two-fold.

“No. 1: Many of our most economically important natural resources come from those volcanic deposits or what happens, like the building of mountain ranges,” Hagadorn said. “And two, a big chunk of our spectacular scenery and landscapes are as the result of these volcanic events.

“So some of our mountains, some of the valleys, some of the Badlands and hills and spectacular vistas that we see – not all of them, but some of them – come from volcanic deposits.”

One of those amazing bits of scenery is the Dotsero volcano which – even though it’s not active in the same sense as the ones in Hawaii Volcanoes National Park – is a fascinating snapshot of what makes Colorado, Colorado.

Perhaps Shorey sums it up best: "Geology is awesome."

> This is a 9NEWS project to make sure what you’ve heard is true, accurate, verified. Want us to verify something for you? Email WebTeam@9NEWS.com.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Colorado’s History