Mark Koebrich and 9NEWS Chief Photographer Eric Kehe have assembled a 30-minute special on the work being done locally on Alzheimer's. It is called "New Hope for Alzheimer's," and it will air on Saturday night on Channel 20 at 9:30 p.m.

In the story below, Mark and Eric are examining the links and mechanism by which Alzheimer's disease and Down syndrome arise. They are also looking at another patient population that, because of their condition, is virtually "insulated" from acquiring Alzheimer's.

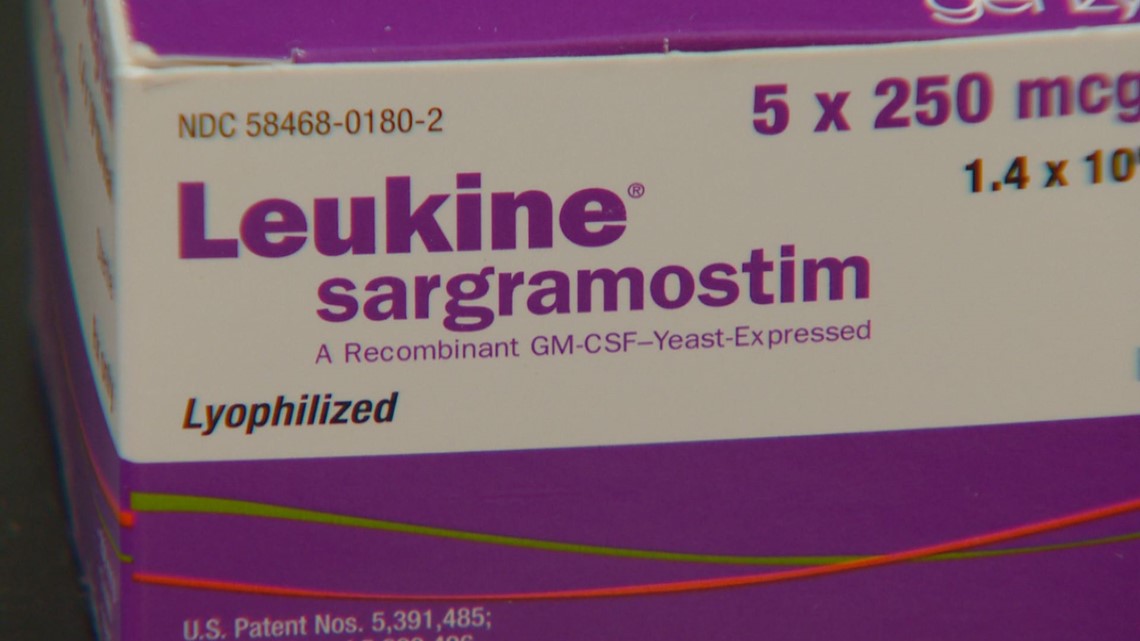

KUSA - 9NEWS has been reporting extensively about a drug called Leukine that may prove to be the first treatment capable of reversing many of the effects of Alzheimer's. That's important because presently, Alzheimer's remains the only major disease in our country without a prevention, treatment or cure.

Someone new is diagnosed with the disease in the U.S every 66 seconds. In 2017, Alzheimer's and other types of dementia will cost the nation $259 billion.

Researchers are racing to find a solution, and many believe one key may be hidden in the biology of the Down syndrome population. There are doctors at CU Anschutz for example, who refer to people with Down syndrome as "a medical gift to society." That's because their unique biology makes them a blueprint for medical research in areas that include heart disease, immune systems disorders, soft tissues cancers and perhaps most importantly at this moment in time, Alzheimer's disease.

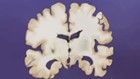

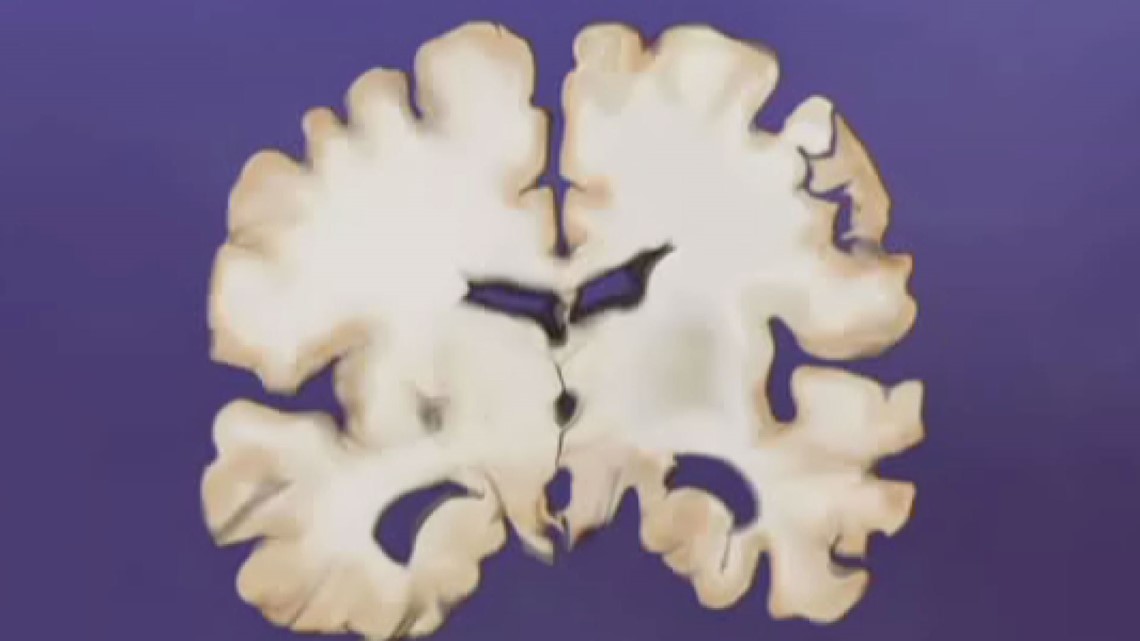

People with Down syndrome begin to develop the plaques and tangles synonymous with Alzheimer’s disease in their brains in their teen years. Virtually 100 percent of people with Down syndrome are expected to have these plaques by the time they are in their forties; however, it is estimated that 30 percent of them will not have the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease, including dementia.

9NEWS Senior Source Correspondent Mark Koebrich says that because of that, researchers believe the Down syndrome population may hold the ultimate key to solving the Alzheimer's riddle.

Take for example 54-year-old Robert Thomas Hallin. He is a person with Down syndrome, and is now dealing with Alzheimer's. He lives with and is cared for by his oldest sister Julie Hallin Weldon and her family in Parker.

In conversations with Robbie, one of the first things he will tell you is that he's a cool person.

As his memory begins to cloud, he has Julie, and the rest of a large and loving family, to fill in the blanks.

"That's true," Julie said. "They're pretty awesome. And they all love their Uncle Robbie."

"They all love their Uncle Robert," Robbie said immediately, flashing his trademark wide grin.

They noticed recently Robbie was slipping, that he was a little less social, was occasionally getting lost and doing other things out of character.

"And he also lost quiet a bit of weight and I he think he wasn't remembering to eat," Julie said.

He was forgetting to eat even though he was working at a Wendy's, a job he held for 32 years. He still has pieces of his uniform, and he loves to show them off.

Julie says tearfully the family is terrified at the possibility that Robbie may need institutional care.

"Because I can't imagine him being cared for the way we would. There are so many subtle things that Robbie does, his quirks, that somebody else isn't going to understand."

For Robbie and the millions like him, it is a virtually inescapable outcome. Dr. Huntington Potter, the Director of Alzheimer's research for the Linda Crnic Institute for Down syndrome at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, says people with Down syndrome cannot, for the most part, escape the Alzheimer's diagnosis.

"By the time they are 50 or 60, most but not all get demented," Potter told 9NEWS.

He explains it's all a function of Chromosome 21, present in two copies in almost everyone, but people with Down syndrome have three copies.

"The main Alzheimer's gene is on Chromosome 21, and so they have an extra copy and that means they make extra amyloid Alzheimer protein, and they begin to get the extra Amyloid deposits of Alzheimer's in their teenage years. By the time they are 30 or 40, their brains look like an Alzheimer patient's brain," Potter said.

However, a small percentage do not lose function to the condition, and Potter says therein lies a possible clue.

"And so we'll be studying the people who do get demented and the people who don't, to get an insight into why there's that difference," Potter said.

At the other end of the spectrum, there exists another population that is largely insulated from the ravages of Alzheimer's. Dr. Kevin Deane says his patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis are only rarely diagnosed with the disease.

One reason is that all of those inflamed joints in an arthritis patient are apparently generating, among other things, lots of naturally occurring Leukine.

"That is where it would start," Deane said. "It would then travel around the rest of the body and perhaps have beneficial effects elsewhere, such as in the brain, to help dissolve plaques formed in Alzheimer's disease."

Leukine of course is the very drug created synthetically, now in trials at CU Anschutz, that has been shown to be a very effective at dissolving plaques. It could very well become the first in a new class of drugs that could actually reverse the progression of Alzheimer's.

While we wait, studies continue on two segments of the population, with two unrelated conditions, people with Down syndrome and Rheumatoid Arthritis, that separately may hold yet another key to the riddle that is Alzheimer's.