Neighborhoods change.

Harlem today has become a hot real estate market as well-heeled buyers flood into the northern end of Manhattan seeking bargain properties.

The Harlem of recent decades, by contrast, was often synonymous with poverty and crime.

But Harlem 100 years ago was ground zero of an explosion of arts, politics and culture in black America. The Harlem Renaissance — known then as the "New Negro Movement" — saw the rise of jazz, the launch of such literary careers as Langston Hughes' and Zora Neale Hurston's, and a new sense of black identity and pride.

It wasn't just in Harlem. Chicago, Cleveland and other Northern cities saw similar cultural and artistic movements, born out of the massive migrations of African Americans from the rural South, first to Southern cities and then into the North.

"This is a period when the majority of black people in the United States are born as free people — the first generation when they're not largely born as slaves," says Minkah Makalani, assistant professor of African and African Diaspora Studies at the University of Texas at Austin.

But they still faced racial oppression and violence in the South, Makalani says, so "they find their way out of that and create some of the most vibrant artifacts and cultural practices that literally inform everything in the American culture today, be it dance, music, writing, poetry. It's a very vibrant robust period.

"You also have these kinds of compelling commentaries on democracy, on politics, on what a just society will look like. They're having these profound discussions about what does it mean to be a democracy, what does it mean to be a world power, where do black people fit in. And it's not monolithic."

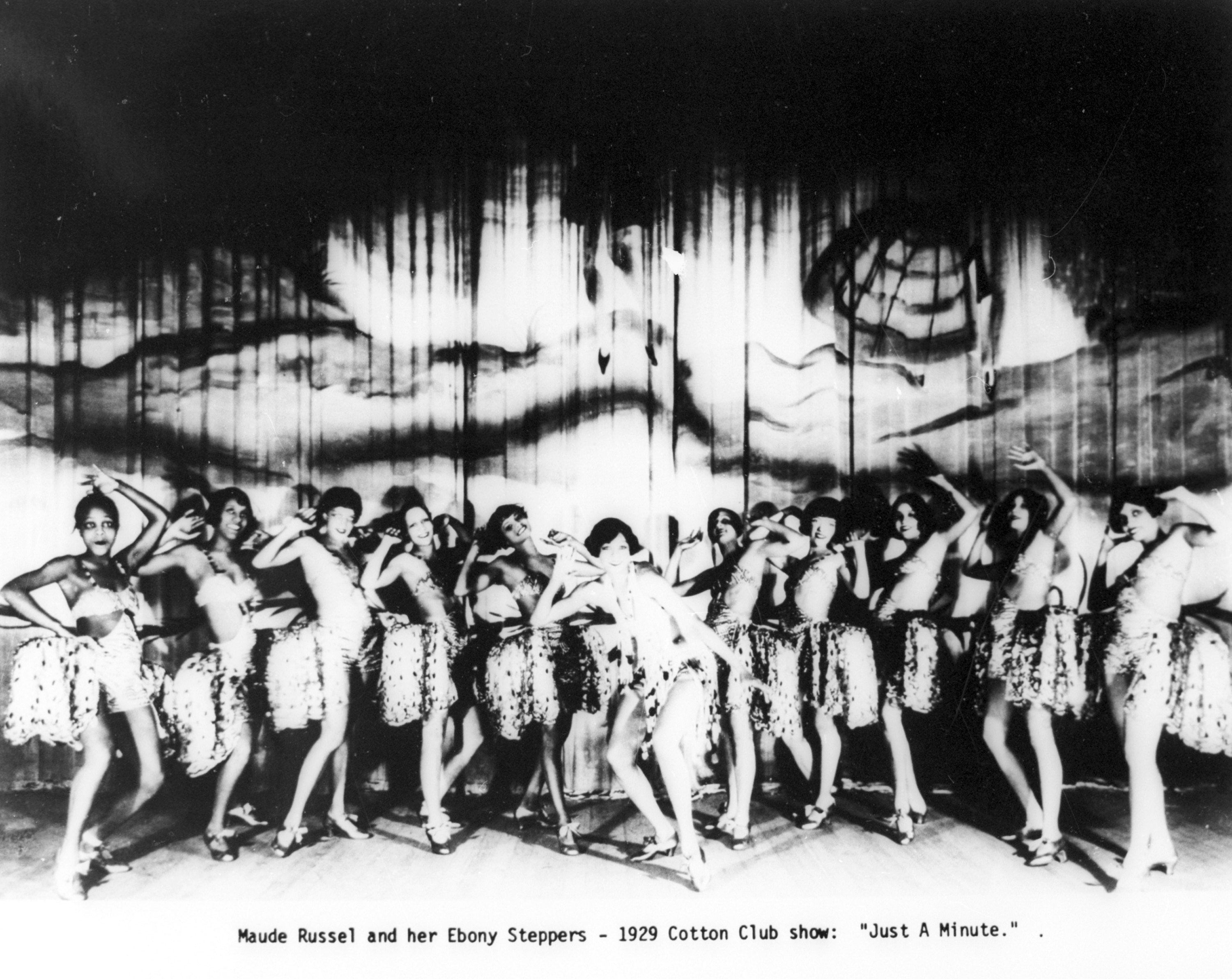

The people and places associated with the Harlem Renaissance are a roll call for American letters, art and thought: musicians Billie Holiday and Louis Armstrong; writer Wallace Thurman and mural artist Aaron Douglas; world-famous venues such as the Cotton Club and the Apollo Theatre; and United Negro Improvement Association founder Marcus Garvey, known as the "black Moses."

The prospect of jobs added to the allure of Harlem and other areas of the industrialized North, but people also were motivated to migrate by Jim Crow laws and other racial oppression in the South, says Davarian Baldwin, the Raether Distinguished Professor of American Studies at Connecticut's Trinity College.

"Part of the reason for their leaving was political," Baldwin says. "They already were prepared and engaged and remaking cities. They brought with them new expectations. They had to engage in debates not just with whites but older, more affluent African Americans in the North."

Those Southern migrations north coincided with huge migration trends across the globe, leading to convergences of numerous different groups in places like Harlem and political and cultural flourishings growing out of that, Baldwin says.

"Ford (Motor) really went out of its way to hire African-American workers for the first time," says Charles Lester, visiting assistant professor of history at Pennsylvania's Albright College. "All these job opportunities are drawing farmers to places like Detroit and Chicago and New York. The net effect is over 1 million Americans leave the South in a 20-year period. Half end up in five cities — Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, New York City and Pittsburgh. As you might imagine, it's going to create a lot of cultural side effects."

However, Makalani adds, "A lot of the stuff we see when we think of the Harlem Renaissance is already taking place in the South. Jazz is taking form in places like New Orleans and has roots in the blues and gospel and reflects this fantastic artistic imagination among black Southerners, and takes on a different life" in the North."

Of Northern communities experiencing this boom in African-American culture, Harlem disproportionately "gets a lot of the love, you might say," says Lester.

"In a lot of ways, Chicago dwarfs what's going on in Harlem, but it hasn't gotten the publicity," Lester says. "There are similar things going on in all kinds of cities. Memphis had Beale Street. Kansas City had a whole vibrant area around 12th Street. A lot of artists leave New Orleans and end up in Chicago."

While the Harlem Renaissance was centered in large part on literature and visual culture, "if you open it up to a wider understanding, Chicago was (author and filmmaker) Oscar Michaeux, Thomas Dorsey and gospel," says Baldwin.

Harlem got so much attention in part because New York was such a hub of publishing. "These were the ways we measure renaissance at that time — arts and letters," Baldwin says.

And Alain Locke's 1925 anthology The New Negro: An Interpretation, "really sort of exposed the broader American public to this cultural flourishing," Lester says. "They really went out their way to trumpet Harlem as the place. That work was very influential at the time."

Today, if there's a city having a Harlem-like flowering, it might be Atlanta, Lester says: "Atlanta has had this cultural explosion of the last 20, 30 years. African Americans feel safe to move to the South for the first time since the dismantling of Jim Crow. That's leading to a whole new cultural exchange."

Daneman also reports for the Rochester (N.Y.) Democrat and Chronicle.