'The species is in trouble': Race is on to save Colorado's tiny alpine toad

There might be only 800 adult boreal toads left in the state due to a deadly fungus, according to wildlife officials.

Chapter 1 The culmination of a journey

High above Pitkin, a couple dozen conservationists and volunteers from Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) and Denver Zoo trekked to the banks of a shallow pond. They stepped softly, eyes glued to the ground, on the hunt for a tiny amphibian.

"It's some great toad habitat," said Stefan Ekernas, the zoo's director of Colorado field conservation. "Lots of insects."

As the team spread apart, an excited cry rang out.

"Did you find one?" Ekernas shouted, picking up the pace to inspect the discovery. "Oh, look at him!"

A colleague passed the boreal toad to Ekernas as a photographer took a barrage of shots. The find was worth celebrating.

Critically endangered on the state level, boreal toads are Colorado's only alpine toad species. They live between elevations of 8,000 and 12,000 feet. Only three other amphibian species share that habitat.

They used to be so numerous that hoards of them dined on bugs under mountain town streetlamps. Now, though, because of a deadly fungus, CPW biologists think that only 800 adult toads are left in Colorado.

"To see them surviving out here in this beautiful spot is pretty amazing," Ekernas said.

RELATED: Endangered boreal toad tadpoles released into the wild by Denver Zoo, Colorado Parks & Wildlife

The crew didn't end up here by chance. This spot is one of the few places left in the state where the chytrid fungus – the primary killer of boreal toads – has yet to invade.

They weren't just looking for toads, either. They brought 570 tadpoles to the pond to release them.

"We're just acclimating them, getting them comfortable with their new water source," Ekernas said, pointing to bags, full of tadpoles, scattered around the pond.

It was the culmination of years of work, the end of a process for the zoo that started with a refrigerator in a new building and a few dozen hibernating toads.

Chapter 2 Canaries in a coal mine

"I like to focus on species that no one really knows about," said Tom Weaver, Denver Zoo's assistant curator of ectotherms.

In a corner of a small building at the edge of the zoo's campus, he opened a fridge and showed off containers stacked from top to bottom.

"These are all toads in these containers," he said. "They basically sit in a stupor over winter."

That stupor is called brumation – hibernation for amphibians and reptiles. In nature, boreal toads burrow into willow shrubs and holes around their ponds and enter into brumation beneath the snow pack. The zoo has to re-create the wild.

"You have to manipulate their internal clock," Weaver said.

He wakes the toads up in May, feeds them, hits them with hormones and breeds an assurance population to release into the wild. The goal of the project is to keep the wild population stable so the boreal toads survive long enough to develop a resistance to chytrid fungus.

"We see this as a long-term, multiyear effort," Ekernas said. "The species is in trouble. It's not gonna be a two-year solution. It's going to be a 10 year or more solution."

He called the toads a "canary in a coal mine" for alpine wetlands.

"They breathe through their skin, so anything that’s in the water also gets in the animals," he said. "So the first thing we’ll see that’s getting hit if the ecosystem isn’t healthy is we’ll see it in amphibians."

> How conservationists are working to save boreal toads:

RELATED: Boreal toads are endangered in Colorado. The Denver Zoo and CPW have a plan to bring them back

Ekernas said that Colorado would lose a symbol of its wetlands if boreal toads get wiped out.

"Those wetlands will be worse, they won't be as alive and thriving as they are now, and that would be devastating," he said. "We'd lose a really important part of Colorado."

Chapter 3 A string of successes

The zoo's boreal toads hibernated in brumation in their fridge until May, when Weaver woke them up.

"When we first took them out, I was like, 'oh man, they're just out of hibernation,'" he said. "When we started feeding them, their eyes perked up and they were like, oh, it's food time."

Weaver started out the toads in a strictly land-based enclosure, but they need water to lay their eggs, so eventually he moved them into a half-and-half environment.

"The biggest thing when you turn it from land to aquatic, you have to be very careful with your ammonia levels," he said.

Weaver and his colleagues got it right, and one morning he saw what everyone was waiting for.

"If you look in here, you can see the string of little black or brown balls, those are all eggs," he said. "We don't know if they're fertile yet, but we do have eggs from five of the 10 groups."

It doesn't take long for the eggs to hatch – just a couple of weeks to see how many tadpoles they'll get.

"Hopefully one morning we'll be in here and we'll have tadpoles swimming," Weaver said.

Chapter 4 Hundreds of tadpoles

"To me, it's really awesome to be here and seeing these guys doing their thing," Ekernas said.

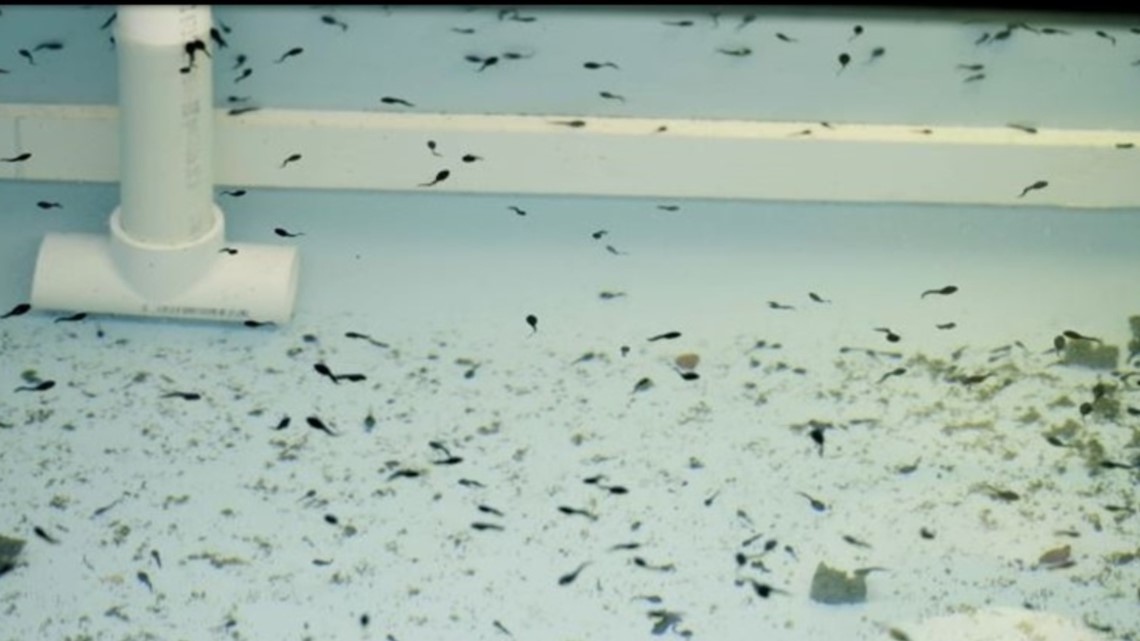

By the end of May, the eggs were gone, and hundreds of tadpoles were swimming around in their now fully aquatic tanks.

"We're feeding them up, so they're ready to grow," Ekernas said.

The tadpoles represent a step in the long journey of helping boreal toads survive in the wild. Because this is a long-term project, the tadpoles' parents won't go into the wild with them.

"These animals will always be here," Weaver said. "We'll keep them healthy and able to physically reproduce."

Chapter 5 Something to be proud of

At first, it didn't seem like the weather would ever cooperate. The pond where the 570 tadpoles were about to be released sat right at the edge of the tree line, where there weren't many places to shelter from elements.

"Avoid all the hail because it might kill you," Ekernas joked.

As the last boom of thunder echoed off the surrounding peaks, though, the sun began to shine and the pond stilled.

"It's amazing to be in this spot, helping this toad," Ekernas said.

He looked for a CPW partner before dumping out the first bag of tadpoles.

"It's just such an amazing opportunity to bring out an endangered species and help it thrive in the wild," he said. "That's kind of a once in a lifetime opportunity, really."

Weaver agreed.

"When I go back to the zoo, I'm going to take this with me and realize our efforts went to something we can really be proud of and know we made a difference," he said.

As summer turns to fall in the Gunnison National Forest, the tadpoles become juvenile toads. They'll find their own burrows to hunker down in for the winter, and, eventually, some of them will grow into breeding adults.

One day, the zoo and CPW hope projects like this won't be necessary. Until then, they'll build on this small step to save Colorado's only high alpine toad.

Endangered Boreal Toad Tadpoles released into wild by Denver Zoo, Colorado Parks & Wildlife

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Animals and Wildlife