Candidates who collect signatures to get their name on the election ballot don't always need to follow the rules exactly to qualify.

The Secretary of State's Office is responsible for reviewing the petitions and determining if the signatures collected are valid or invalid.

Throughout the last few weeks, the Secretary of State's Office has determined whose petitions were sufficient and insufficient to qualify for the ballot. You can read about the fate of each candidate here. Candidates like Republican gubernatorial candidate Doug Robinson and Republican treasurer candidate Brian Watson failed to gather enough valid signatures.

They took the Secretary of State to court to "cure" enough signatures to get to the threshold needed to qualify. Those signatures could have been invalidated because they were illegible, missing an apartment number for the voter's address or maybe because they were registered as a Democrat. They both successfully won their argument to cure enough signatures to qualify.

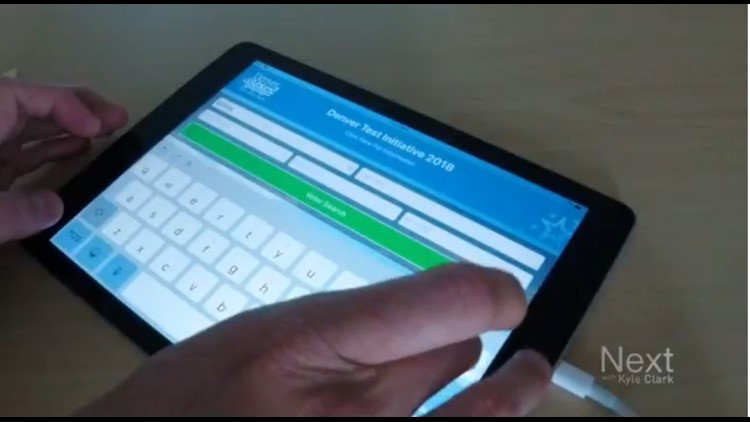

Elections in Denver wouldn't have to go through the lawsuits because the elections division does signature collection like it's 2018. The city uses iPads to collect signatures digitally.

"We've had this deployed in use in Denver since 2015," said Amber McReynolds, Denver Elections Director.

The app is loaded with voter registration information. A potential signee types in their name, address number, zip code and birth year and the app pulls up the voter's record. The app also tells the signature collector, based on color codes, if the signee is eligible to sign based on their address, party affiliation or if they've already signed another petition.

The voter then signs the iPad with a stylus.

"This makes the process more transparent for candidates and campaigns," said McReynolds.

The city still has to verify that the signature matches the voter's signature that they have on record, but this system eliminates the problems with missing address information and sloppy handwriting.

"We have talked to the state for the past year-and-a-half or so and gave them various demos," said McReynolds. "We demoed it for a few candidates that were running for statewide office. The state, what they shared with us, late last year, they felt that they didn't have enough time to get it implemented."

"We would love to use something like this," said Colorado Deputy Secretary of State Suzanne Staiert. "It's not going out in the format that's required by state law."

State and federal candidates and state ballot issues still have to use old-school signature collection techniques: pen and paper. State law is so specific, Staiert said she believes the state can't use it until state law is rewritten in modern language.

"It has to be printed on a sheet, and how the signer should sign in black ink, and how it has to be fastened at the top, and as you know these are things that don't apply to an iPad," Staiert said. "There is a massive amount of litigation related to these petitions. You can be sure that if we tried to circulate a petition like that, without changing these sections of the law related to black ink and paper sheets and all these kinds of things, then those petitions would be challenged in court."

What else is new?

On the back end of the process, the petitions are printed and can be fastened with a staple or paper clip. The only thing is that the names are printed, not in ink.

The city of Denver created the program and even licensed it to the Washington, D.C. Board of Elections. Though it's not a money maker for the city, they only charge what it costs to run the program.

Bottom line, the state would be interested in moving to a digital process, but state lawmakers need to change the wording of election law.

And even if this were in place, the signature issues that took Rep. Doug Lamborn, (R-Colorado Springs), to a federal courtroom to solve, would not be solved with an iPad. His issue was that two signature collectors were found to have not met Colorado's residency requirement. On Tuesday, a federal judge ruled that the signatures collected by out-of-state petitioners can be counted for Lamborn.

"Two of our pieces of litigation this round haven't been about the signatures, they've been about whether or not the circulator is actually a resident of the state, and that's not something that this kind of technology is going to detect," Staiert said.