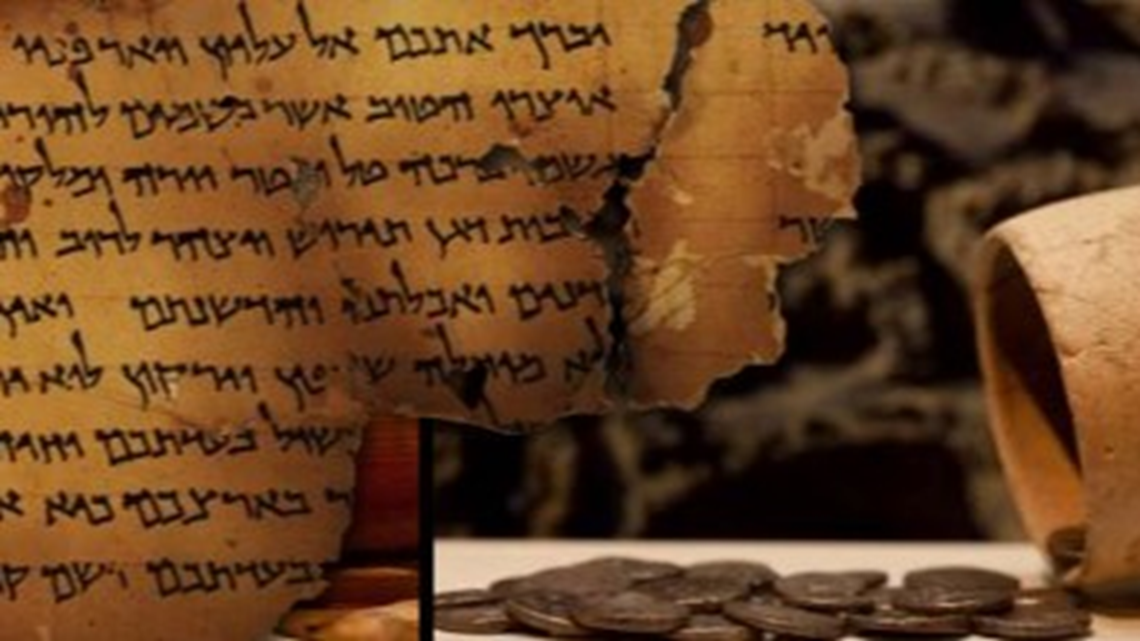

You don't have to be a history nerd to appreciate the importance of the Dead Sea Scrolls - ancient manuscripts dating back over 2,000 years, which include laws, poetry and some of the earliest biblical documents.

People can see some of them now at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, including at least one that's never before been seen by the public.

As people head to the museum to appreciate the documents, a three-person "editor-in-chief" team is working to create a new translation of them from the original Aramaic, Hebrew and Greek languages. One of the editors is Alison Schofield, who teaches Judaic and religious studies at the University of Denver. She has spent the last decade traveling to Israel working with the manuscripts, as well as trying to get them on display in Denver.

"There is so much yet to be known about these texts, and yet, they are so important for us to reveal a window of a hidden time, really, in terms of preservation." she says. "A time when Judaism and Christianity come into being, and they hold a lot of the key for us to understand this period."

The first scrolls were found near the Dead Sea in 1947, but the scholars who had them didn't make them openly available until the 90s, Schofield says. She's currently working on a more thorough version of the early translation of scrolls found in "Cave 1" of 12 - the first place they were discovered.

Several people wrote these manuscripts, mostly on leather with a carbon-based ink, but she doesn't know specifically who they were; different handwriting does help distinguish one author from another, and scholars mostly believe them to be men.

The content is diverse. The writers say they believe they're at the end of the world, they mention searching for a Messiah, and they describe themselves as being the most pure and righteous people, Schofield says.

"I find nuggets of humanity in these texts, where we see jealousy, we see descriptions of anger, and backbiting. Things that just seem sort of normal, but just seem fascinating to me that this was going on over 2,000 years ago," Schofield says.

She's the first woman to be an editor, a job that was previously held by one man for decades. The scrolls have been a passion of hers since she was a teenager. Schofield, who has a PhD from Notre Dame, turned the scrolls into a career by studying languages and history, and through diverse training over years.

"This is an extension of the sandbox for me, in the sense that as a kid I liked to find things, dig up things, and then put them back together," she says.

Schofield can read the manuscripts easily, if you will - without notes or special references. But if she's one of a few experts, how do we know she's reading them accurately?

"We luckily have a cohort of scholars around the world, those of us who know how to read these things, and we're continually checking up on each other," she says.

Daniel Falk from Penn State University and Martin Abegg Jr. from Trinity Western University are working with Schofield.

Many scrolls are on display now at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. The Denver exhibit opens Friday.

Next often profiles people with interesting careers. If you know someone with one of those, and think, "That's a Job?" let us know: Next@9news.com.

RELATED STORIES: