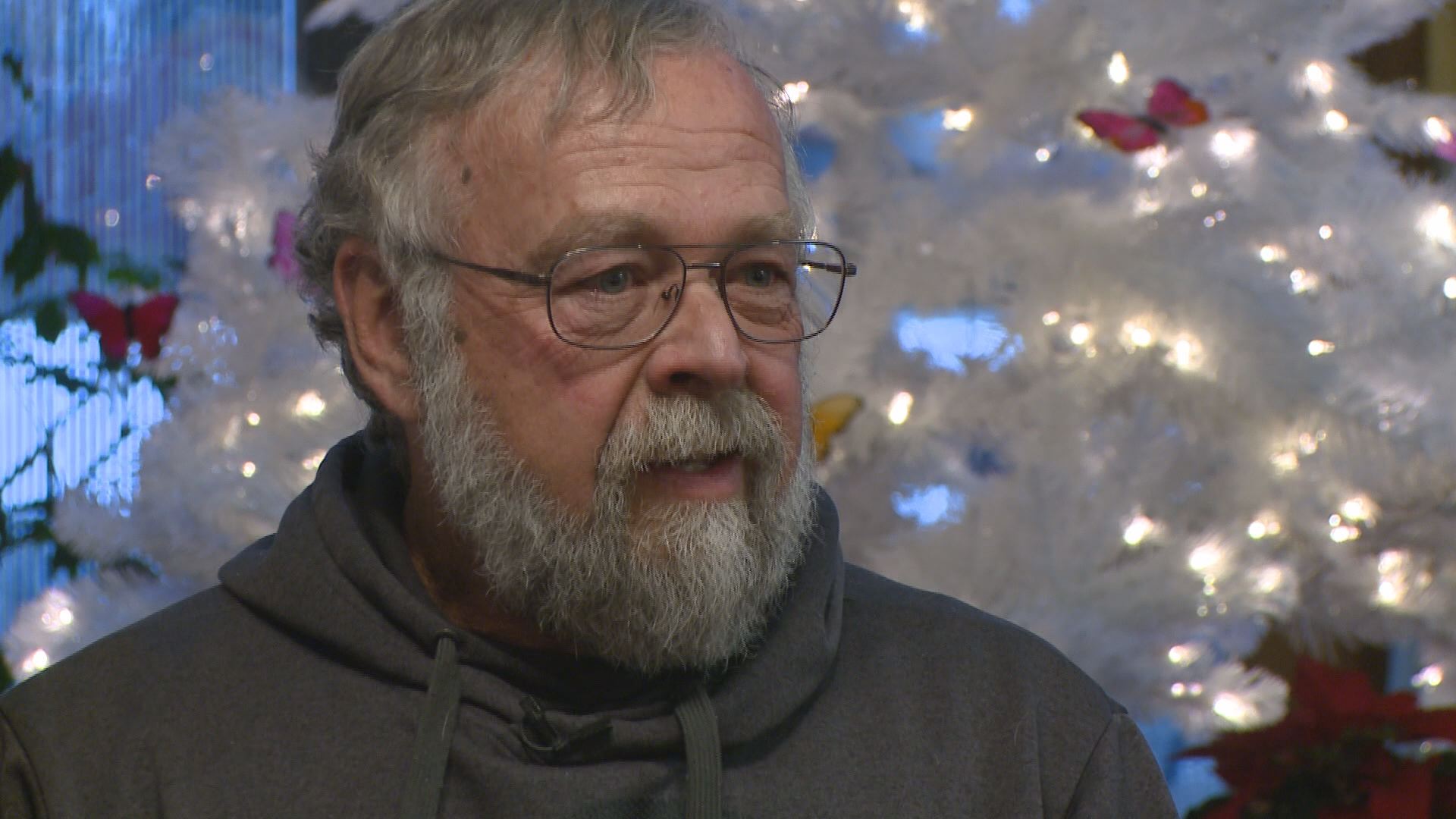

It's Christmastime again. Herb Myers has seen dozens of holiday seasons during his life. But this is the first time in 40 years he's celebrating without the love of his life.

And while it's getting a little easier - it's never going to be easy.

Last year, Herb asked his wife, Kathy, what she wanted for Christmas. She told him she wanted to die.

And he would help her - after 38 years of marriage - die peacefully in their home.

Kathy Myers started smoking when she was 12. Eleven years ago, she was diagnosed with COPD. Her conditioned worsened over time. She was put on an oxygen tank, then she spent months in hospice care.

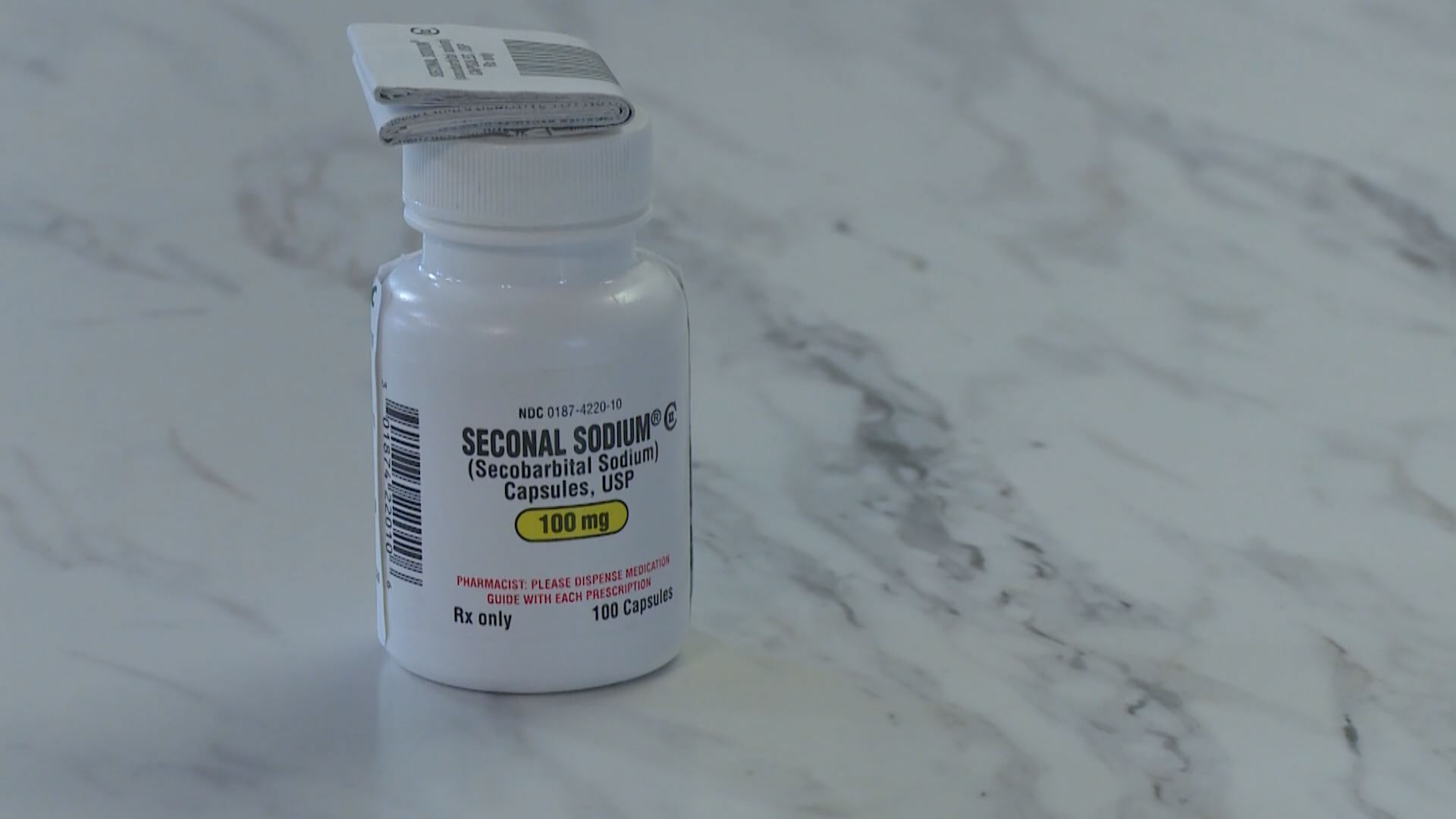

Last December, Colorado legalized assisted-suicide. Kathy and Herb then did everything they could to find a doctor who'd prescribe them what they needed to end her life.

It took a long time. Eventually, she was able to get the pills that would end her life. In April of this year, on a Sunday, she died peacefully in her home, surrounded by her family: her husband holding one hand and her daughter holding the other. Kathy was the first known person in Colorado to end her life under the aid-in-dying law.

Catching up with Herb

A year later, 9NEWS reached back out to Herb to talk about his life since the moment his wife died.

He said he likes the law as it's written and believes there are adequate protections for doctors and any organization that wants to help people with assisted-suicide.

He did add that there's always room to improve.

But his life now, in the 9 months and a few days since?

"Some days are easier than others," he said. "Tuesday, Colorado Public Broadcasting - they did a couple promos and I heard Kathy's voice on them. It was nice to hear her voice but it was really rough, too."

He explained that while he lit up when he heard her voice, that joy was tempered by the realization that he's never going to hear that voice come from his wife again.

"I listened to the voicemails from her the other night just to hear her voice again. You know, it was nice," he continued. "It was sad. But it was good to hear her voice again."

That voice was something he took for granted.

"Every day," he said. "There's not a day that goes by that I don't think of her. The very first time that I had a challenge at work that I was able to successfully complete, I thought - I've got no one to tell this to."

It's those moments that hit Herb.

"It's the first Christmas in 40 years that Kathy and I haven't been together," he continued. "I wasn't gonna put up a tree or anything. I just didn't feel it."

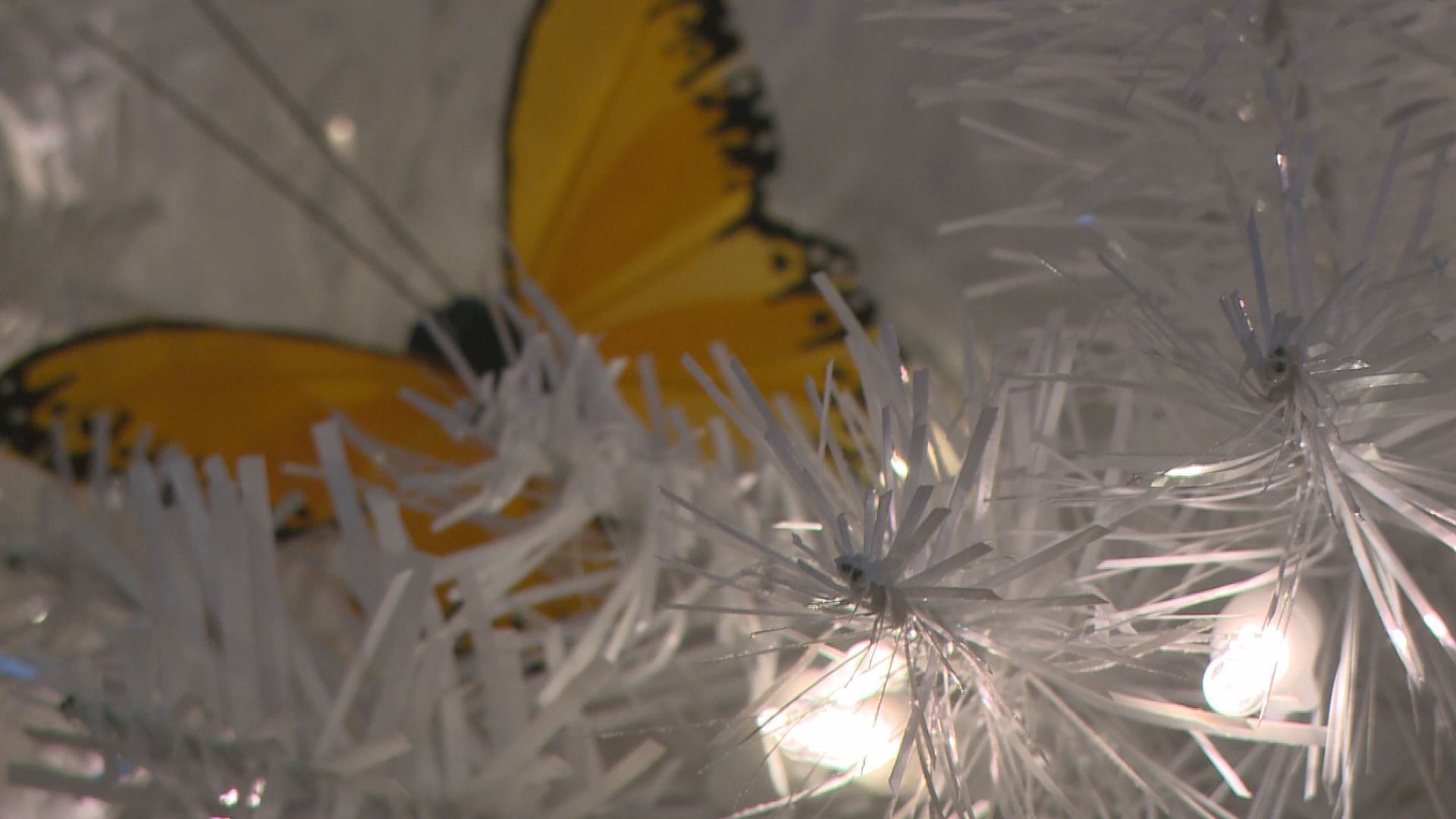

But at a group meeting called Grief Share, Herb got an idea.

"The butterflies are on there instead of ornaments because Kathy said if I saw butterflies fluttering around me that it was her coming to say hi," he said, sitting in front of a Christmas tree with different-colored butterflies strewn all over it.

"It made me think of her," he said.It made him think of the woman with whom he'd spent near countless hours discussing ending it - and even right before Kathy took the prescription Herb said he wasn't sure she really would."The week before we had talked about it a lot," he explained. "Let's go back even further."Last year, at Christmas, Herb asked Kathy what she wanted. Then she told him."I knew that's what she wanted. We had talked about it plenty before and after the law was passed," he said. "But it was a shock to hear her say that."There was a silence between them."And then about a week before she actually took it, we talked some more," he continued. "The night before, I got several different flavors of a sports drink. She picked out the one she liked best."She would need to take the contents of 100 gel caps for it to work. Herb spent an hour and a half rolling the pills, opening them, and then scraping out the contents with a drill bit. Then he added the contents to the drink so it would be easier to take.

"That's one regret I have," he said. "Because that's an hour and a half at the end that I didn't get to spend with her."He said the end was peaceful."She laid her head back on the pillow, we held hands, our daughter was on the other side of the bed and held her other hand," said Herb. "After about two minutes, her grip lightened and I never saw her take another breath."He watched to see if she was in any kind of pain or distress. Herb said he didn't see any signs of it.Herb said that people reach out to him every now and then and ask for help. Their main complaint? Finding a doctor to give them a prescription."I know how frustrating it was with me," he said. "Making all these phone calls to government agencies - just running up with no information at all."But the most common question isn't about how to do it or how to get pills."What was it like at the end," he explained. "Because that's what they're all trying to avoid is a rough end - depending on the drug that's used, it can be rought."The only thing he'd like now is more choices for people."More access. Compassionate Choices is still the number one resource if people are looking for help with this. I believe they are trying to put together a resource where they can put together doctors with patients."A look at the law after one yearA doctor actually found Kathy and Herb after Next interviewed them about their search.Nearly a year after the aid-in-dying law went into effect, people still struggle to find doctors willing to prescribe the medication in Colorado.“It's easier, but it's still not going to be a breeze,” said Kim Mooney, the founder of an end-of-life support organization called Practically Dying.People looking for the medication need to find two doctors to sign off on the prescription. Based on her work, Mooney says the difficulty in finding those doctors is about more than a struggle with the legal or ethical questions surrounding the law. Doctors who are comfortable prescribing the medication are hesitant to publicly say so, not just because of negative feedback, but also because of demand.“A couple that I know did it for one or two people and were inundated by… many other people wanting the help,” Mooney said. “This is a big shift for (doctors), thinking about how to help end a patient's life, but the second thing is that they really want to know the patient.”There's integrity in how a doctor goes about this, Mooney says. Doctors want to know the patient, know their mental state, and make sure each person is handled carefully, not casually.Doctors and advocates also want more information about the people who have decided to end their lives this way. Advocacy group Compassion and Choices estimates 45 to 55 people filled the prescription in 2017, although that does not mean all those people chose to take the medication.State data about the law's first year has yet to be released, and when it is, certain details will be lacking. Doctors can prescribe one of two medications, but the public doesn't currently know which is most often prescribed. Some patients say they're uncomfortable with the amount of time it takes for the medication to take effect. The time varies from person-to-person, and the law does not require people to report their experiences.“We're hearing about the cases that don't work, which is a good thing, but because of the low-reporting requirements, we don't know how many times anything works and doesn't work,” Mooney said.Other patients want to see the law evolve to reflect their personal needs. People with ALS, for example, cannot self-administer, as is required.Mooney wants more official data to be public, so that patients, medical groups, coroners and even funeral directors can find answers to questions they may have.Mooney hopes the process improves more in its second year.“People are doing a lot of legwork on their own, and when you're dealing with a stressful terminal illness, that's not something, I don't think, you need to be dealing with,” she says.Compassion and Choices has created an online tool to point patients in the direction of healthcare facilities that have policies supporting the law. You can find it on their website.You can watch our full interview with Mooney here.