DENVER — Editor's note: This article has been updated to reflect Diggins' correct comments. The article originally quoted him as stating he did not know Brian Hicks, the leader of the gang the Elite Eight. The article has been changed to reflect the following: When questioned in a telephone interview about Hicks and the Elite Eight and the allegations that he let Hicks use an unsecured telephone at the jail, Diggins said: "I'm sorry, I let who do that?" Questioned further, he said: "I don't know what you're talking about." He directed any further questions to the spokesperson at the Denver Sheriff's Department.

More than a decade ago, a confidential informant raised alarming allegations about law enforcement officers in Denver, contending that a top Denver sheriff’s commander tied to a notorious street gang through his brother allegedly did favors for gang members responsible for some of the city’s most heinous crimes.

That sheriff’s commander was Elias Diggins. Those allegations were never fully investigated — and now Diggins is Denver’s sheriff.

In an interview with The Gazette, Diggins denied he ever had any involvement with the gang though he acknowledged that his brother is a gang member.

> NOTE: This story originally appeared in the Denver Gazette and is published on 9NEWS.com with permission. To see the Denver Gazette’s coverage of this story, including images of some of the documents laying out the allegations against Elias Diggins, click/tap here.

For 14 years the informant’s allegations have remained a closely guarded secret, only known by a few select individuals. Two people with ties to law enforcement familiar with the allegations say they pushed, without success, behind the scenes for a deeper review of the informant's allegations and were surprised the city never conducted an internal affairs investigation.

Despite a second corroborating informant, the allegations were never investigated by Denver's internal affairs bureaus or by the FBI. Federal prosecutors were reluctant to pursue a criminal case without additional evidence, especially when other cooperating witnesses did not make similar allegations, recalled a third individual in law enforcement involved in those discussions.

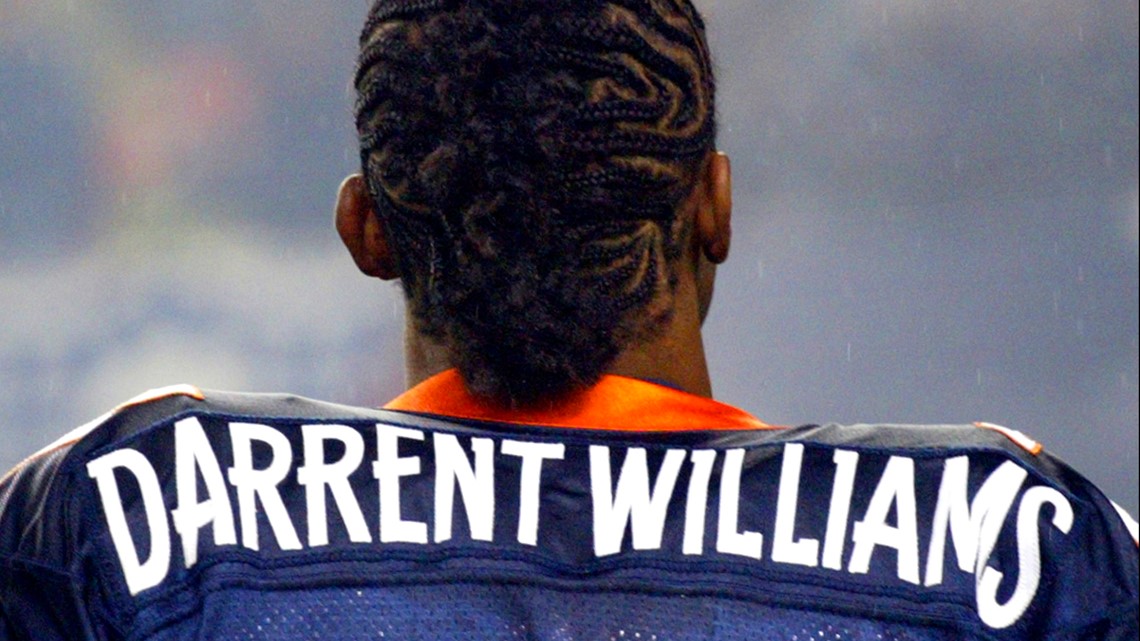

The statements from the two informants have remained shielded from public scrutiny, tucked away in files, even as members of the gang have been prosecuted for monthly crack cocaine sales in excess of $1 million and high-profile murders, including that of Denver Broncos cornerback Darrent Williams during the early hours of Jan. 1, 2007.

The city has declined to probe the allegations from the informants even as dissension has roiled the Denver Sheriff’s Department, stoked in part by word that federal telephone surveillance suggested someone working at the Denver County Jail may have helped the gang's leader when he was incarcerated there by allowing him to use an unsecured desk telephone that was not monitored by law enforcement. Gang unit officers at the department say they were told that surveillance showed calls coming from an unsecured telephone at the jail to associates of the gang leader.

At one point, an open rebellion by members of the Denver Sheriff’s Department gang unit, who feared Diggins was too close to gang members to supervise their work, prompted the city attorney’s office to call in an outside mediator to negotiate a truce. Along the way, relationships between the Sheriff's Department and other law enforcement agencies soured due to fears someone at the Sheriff's Department was leaking information back to the gang, according to people familiar with the situation.

Still, the informants' allegations remained unexplored and unknown to the public.

Until now. The Gazette has obtained statements from the first informant, a founding member of the Elite Eight gang, made in a series of interviews with a federal prosecutor, two FBI agents and local gang investigators.

City officials, when questioned about the informant and the lack of an internal affairs investigation, have rushed to defend Diggins, whom Mayor Michael Hancock named sheriff in July. City Attorney Kristin Bronson in a prepared statement said that the informant’s allegations “are nothing more than old conspiracy theories.”

"The fact that a convicted felon hoping to better his situation provides information to law enforcement does not make the information true, any more than repeating a rumor again and again makes the rumor true," Bronson said in her statement. Bronson did not comment on the fact that other information provided by the informant was deemed sufficiently credible to trigger criminal prosecutions, and resulting convictions, of those outside law enforcement.

The lack of an internal affairs investigation into the matters drew sharp criticism from five retired law enforcement officers — four of whom worked under Diggins — and another individual currently working in law enforcement.

Two former Sheriff's Department employees, former captain Phil Swift and former deputy Rick Ryder, said they separately clashed with Diggins when they questioned whether Diggins was too close to gang members to oversee their work as intelligence officers on the department's gang unit. Both of those former employees said that while they weren't aware of the informant's allegations, those allegations don't surprise them. They said that when they were at the department, they and others had questions about Diggins' loyalties.

"The long history of allegations around corruption in the department, and specifically those that have followed Sheriff Diggins about gang ties, need to be investigated to finally put it to rest and say there is nothing here or to determine that there was something that is wrong or illegal," said Swift, a former investigator in the Denver Sheriff's Department's internal affairs unit who is now a city marshal in Texas. "Currently, it's a stain on the sheriff's department's reputation because of the way it's viewed by outside agencies and the way it hinders the department's ability to carry out its duties."

"The fact that it was believed that Diggins has gang ties, and that he is somewhat empathetic to those ties is well known and discussed throughout the Sheriff's Department," Swift added.

Denver Police Department records obtained by The Gazette, detailing recorded telephone conversations in 2007 of the leader of the Elite Eight, Brian “Solo” Hicks, also show that Hicks himself claimed to know Diggins, back when Diggins was a major. A detective’s synopsis of those recordings, captured on the Denver County Jail’s inmate call system, show Hicks instructed his associates to contact Diggins when they visited Hicks while he was incarcerated at the Denver County Jail and told them Diggins was a "cool dude" who could facilitate their visitations.

“Hicks said that he talked to the major, and he is the boss of everything and he is cool,” the detective reported in one synopsis of a January 17, 2007 telephone conversation between Hicks and a female associate. “He is a black dude. He know me, I know his brother.”

The allegations from the two informants have never been formally investigated, either criminally or by internal affairs investigators, even though records from the Denver District Attorney’s office show officials there found the allegations serious enough that they screened to make sure none of the law enforcement individuals identified by the informants would testify during the murder-for-hire trial of the gang’s leader.

Kelli Christensen, a spokesperson for the Denver Department of Public Safety, which oversees the city's police and sheriff's department, confirmed the city was made aware 14 years ago of allegations that Diggins had gang ties but chose not to conduct an internal affairs investigation because an investigation was deemed unnecessary at the time. She said Mayor Hancock and Executive Director of Public Safety Murphy Robinson were informed of the allegations before they selected Diggins as sheriff in July, but they did not view the allegations, made years ago, as disqualifying.

The Gazette filed a Colorado Open Records Act request seeking details on how the city handled the allegations, but the city's safety department said it could find no records, and that the sheriff's department "did not retain records of not sustained cases pursuant to its record retention schedule."

Swift, who left the department in 2018 to take a new job in law enforcement, and Ryder, who retired from the department in 2019, said the city's lack of any follow up into the allegations is a shame. They said lingering questions over Diggins' alleged ties to gang members prompted other law enforcement agencies to balk at sharing gang intelligence with the Denver Sheriff's Department. They also said that officials with the U.S. Marshals Service grew so concerned over the potential for leaks out of the Sheriff's Department to gang members that the marshals refused to share with the Sheriff's Department details on how witnesses would be transported to a courtroom in Denver District Court to testify in a murder-for-hire trial. The U.S. Marshals Service did not return calls seeking to confirm or deny these allegations.

Ryder, now retired, said he "absolutely" believed an internal affairs investigation should have been conducted and recalled that he once witnessed what he described as a disturbing conversation between Diggins and Diggins' brother, Erique, identified in gang intelligence files as a Tre Deuce gang member. Ryder said that shortly after Elias Diggins was promoted to a division chief position running the Denver County Jail on Smith Road, Ryder passed Diggins' office and saw Erique, his feet propped up on Diggins' desk, telling his brother: "I'm running this bitch now."

"You have to be above reproach, especially when you are in a command position," Ryder said. "It's such a tangled web. There are a whole lot of questions that have never been answered."

Diggins, through Daria Serna, a Sheriff's Department spokesperson, denied having the conversation with his brother. The spokeswoman said Diggins "believes this may be a case of mistaken identity."

Two other retired Sheriff's deputies — Eric Hall and Michael Schaefer — confirmed that Diggins' interactions with incarcerated gang members prompted controversy at the department. They said they separately witnessed Diggins violate the Sheriff's Department's protocols for dealing with gang members, including with his own brother — allegations Diggins denies.

II.

Two other people involved in law enforcement who are familiar with the informant’s allegations said they had pushed for a deeper look. One of those said he was present when the FBI’s command staff in Denver was briefed by telephone on the allegations and recalled that the FBI chose not to investigate further. Another said the informant’s allegations also were referred to Denver public safety officials with the expectation they would trigger a robust internal affairs investigation.

That individual said he was surprised internal affairs investigations had not been conducted and said other agencies where he had worked would have taken a deeper look at the allegations, especially considering that law enforcement officials had forwarded the information on.

The two people familiar with the first confidential informant’s statements who spoke to The Gazette asked that they not be named due to the sensitivity of the matters involved.

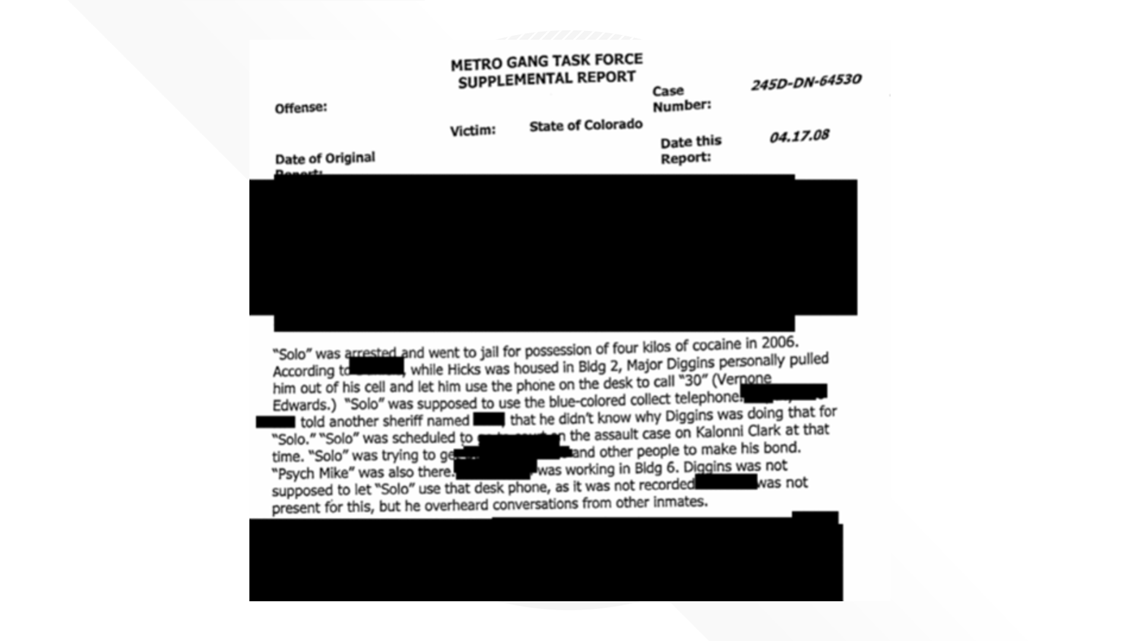

The informant alleged that law enforcement officials agreed to help gang members evade arrest in exchange for money, provided bulletproof vests to the gang and allowed Brian “Solo” Hicks, the leader of the Elite Eight, to make calls on an unsecured telephone line when he was jailed, according to FBI and Metro Gang Task Force memos obtained by The Gazette.

Both Swift and another person with ties to local law enforcement said telephone surveillance identified calls coming from an unsecured telephone at the Denver County Jail to the clothing store owned by Hicks, and to his associates.

The informant told authorities that “people recognized when other people were on the rise,” referring to the gang’s increasing influence at the time, according to one Metro Gang Task Force memorandum recounting his allegations. “The Elite Eight had a whole lot of money at the time. They got a lot of favors.”

The informant also identified Gary Wilson as providing "corrupt assistance." Wilson would go on to become sheriff in Denver from 2010 to mid-2014, but he stepped down amid a series of excessive force cases that had embarrassed the department and cost it millions. He then was demoted from a division chief position for giving preferential treatment to an inmate but had his demotion rescinded after he appealed through the civil service process. He has since retired from the department and moved out of state.

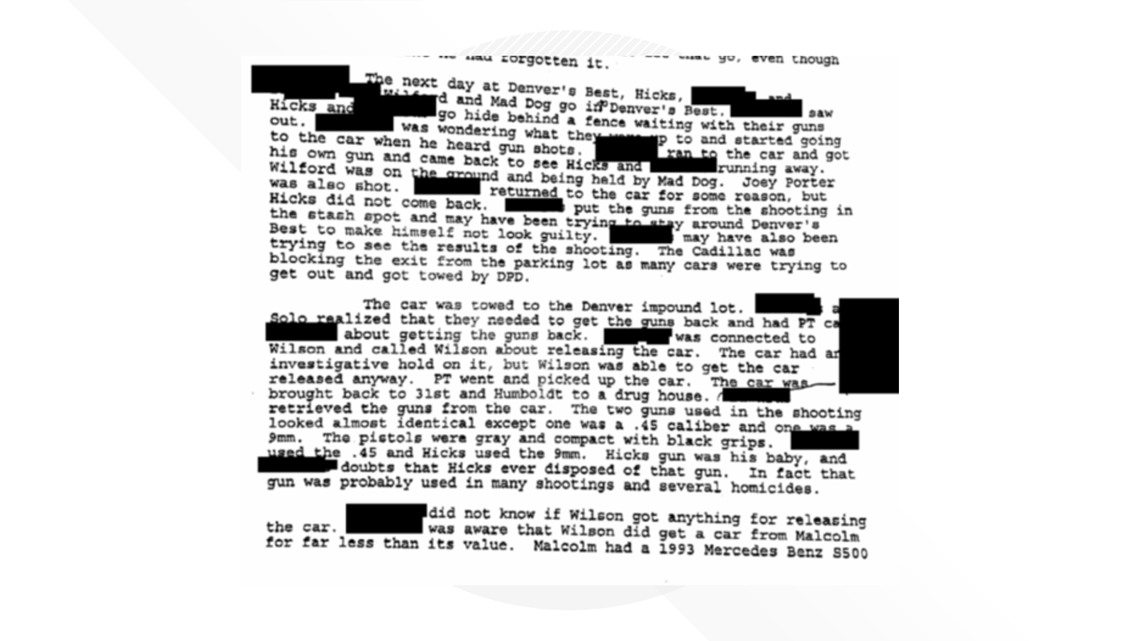

In one instance, Wilson, then a Denver Sheriff's captain, facilitated the return of a car back to the gang that police had seized as evidence in a 2003 murder case, according to the informant. The return of the car allowed the assailants to retrieve from a hidden stash compartment in the car’s dashboard two firearms used in a gang-style slaying, the informant alleged.

Wilson did not return telephone messages, text messages and emails seeking comment. Wilson also did not respond to messages left with an acquaintance.

The informant alleged that Hicks and one of Hicks’ enforcers had killed a member of the Tre-Tre Crips, Chris Wilford, when they shot a spree of bullets into a parking lot outside the All Sports Bar & Grill in Denver. Wilford was killed and five others seriously injured, including Pittsburgh Steelers linebacker Joey Porter. That killing was never officially solved or prosecuted.

Police impounded as evidence the gang’s Cadillac DeVille, which had a secret compartment where Hicks’ enforcer had hidden two handguns used in the murder, the informant said. Working through a local used car lot known as being owned by a drug trafficker, Hicks had Wilson release the Cadillac from the impound lot back to the gang, the informant said.

“The car had an investigative hold on it, but Wilson was able to get the car released anyway,” according to an FBI summary of the informant’s statement. The informant said that a 9 mm handgun that Hicks used in the murder was hidden in a “special stash spot behind the light switch,” and that the release of the car back to the gang allowed Hicks to retrieve the gun, which “was his baby,” the summary of the informant’s interview states.

“In fact that gun was probably used in many shootings and several homicides,” according to the summary The Gazette obtained. The informant said another handgun used by Hicks’ enforcer also was retrieved from the secret compartment.

The informant said he wasn’t sure if Wilson got anything of value in return for releasing the car back to the gang, but he said Wilson bought a car from a gang member with ties to the used car lot for far less than its value. The informant told authorities that Wilson, through gang ties, bought a Mercedes Benz for $12,000 when the car had an original asking price of $36,000. Law enforcement investigators say they later confirmed that Wilson owned the car described by the informant.

Other law enforcement officials identified by the informant as aiding the Elite Eight gang denied the allegations against them. Michael Hall, one Denver police officer identified by the informant as supplying the gang with bulletproof vests, has since died.

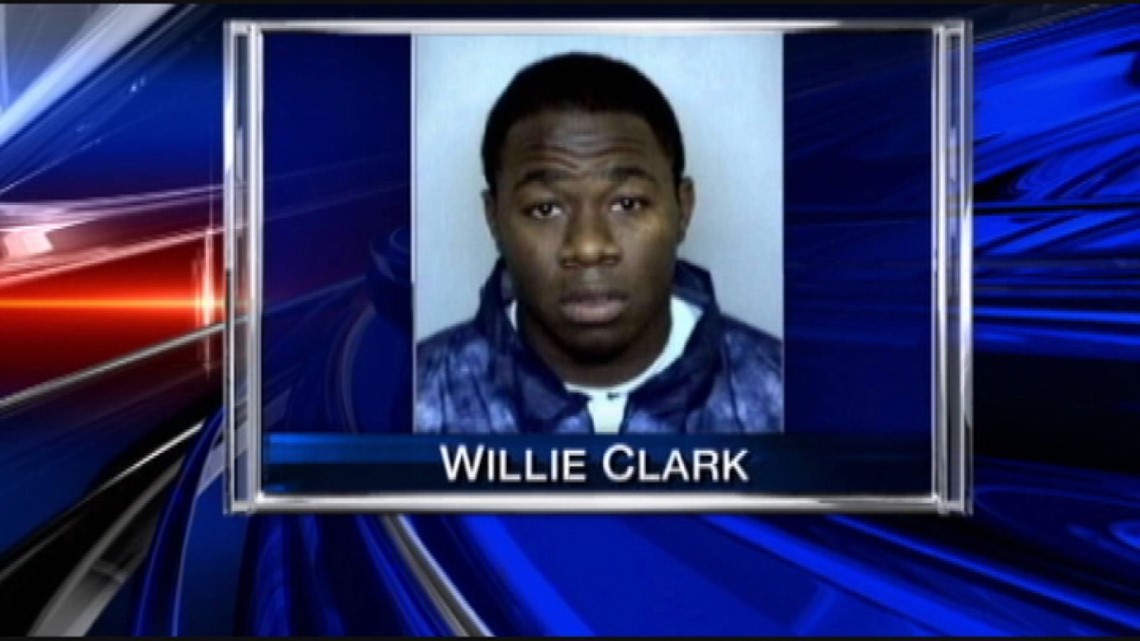

The statements were made more than a decade ago by a founding member of the Elite Eight in interviews with investigators and a federal prosecutor trying to solve a string of homicides in Denver. The gang was known for savage violence, including the 2006 shooting death of a witness, Kalonniann Clark, and the drive-by slaying of Williams, the popular Broncos player. Willie Clark, a member of the gang's parent organization, the Tre-Tre Crips, was convicted of murdering Williams and of murdering a witness for the Elite Eight's leader and was

sentenced to life in prison.

(In the video below, Clark talks to 9NEWS' Paula Woodward in a 2008 jailhouse interview.)

The four law-enforcement officials the informant identified as corruptly assisting the gang’s rise to power were never charged criminally, though investigative records show federal law enforcement officials were aware of the informant’s allegations. The FBI did not respond to a request for comment. However, information the informant provided to the FBI and the Metro Gang Task Force and federal prosecutors proved helpful to them in prosecuting gang members, including the eventual convictions of the Elite Eight's leader, Hicks, and others.

III.

Two people familiar with the details said there was a lack of corroborating evidence to build criminal cases against law enforcement individuals the informant identified, including against one of the named individuals, Diggins.

The two individuals with ties to law enforcement familiar with the informant’s statements said the FBI was alerted along with other local authorities, but there were jurisdictional hurdles and manpower issues that prevented follow-up that would lead to a robust public corruption investigation despite the informant’s statements raising suspicions.

Federal authorities were more concerned about making cases on drug-trafficking charges against the gang and believed the allegations would require further corroboration to pursue, they recalled.

“There were so many tentacles that you had to pick and choose what you could do,” one person familiar with the statements from the informant said. “In the end the dope cases were what the federal prosecutors wanted.”

One of the individuals with ties to law enforcement familiar with the informant's allegations said he was present when the FBI’s command staff in Denver was briefed by telephone on the allegations and recalled that the FBI chose not to investigate further. A third law enforcement individual familiar with the situation said federal prosecutors were also briefed, and that those prosecutors agreed there wasn't sufficient evidence for a case.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Stephanie Podolak, the federal prosecutor who helped interview the informant, declined comment.

Former Denver Police Commander John Lamb, who was in charge of internal affairs for Denver police during the time of the informant's allegations, and former Denver Sheriff Division Chief Phil Deeds, who was in charge of the Denver sheriff's department internal affairs back then, both declined to comment.

Bill Lovingier, who was Denver Sheriff at the time but has since retired, said he couldn't recall why an internal affairs investigation wasn't conducted.

"I remember hearing about the allegations, but obviously nothing was ever substantiated," Lovingier said. "I remember the talk and conversation, but it's been too long ago for me to remember the specifics."

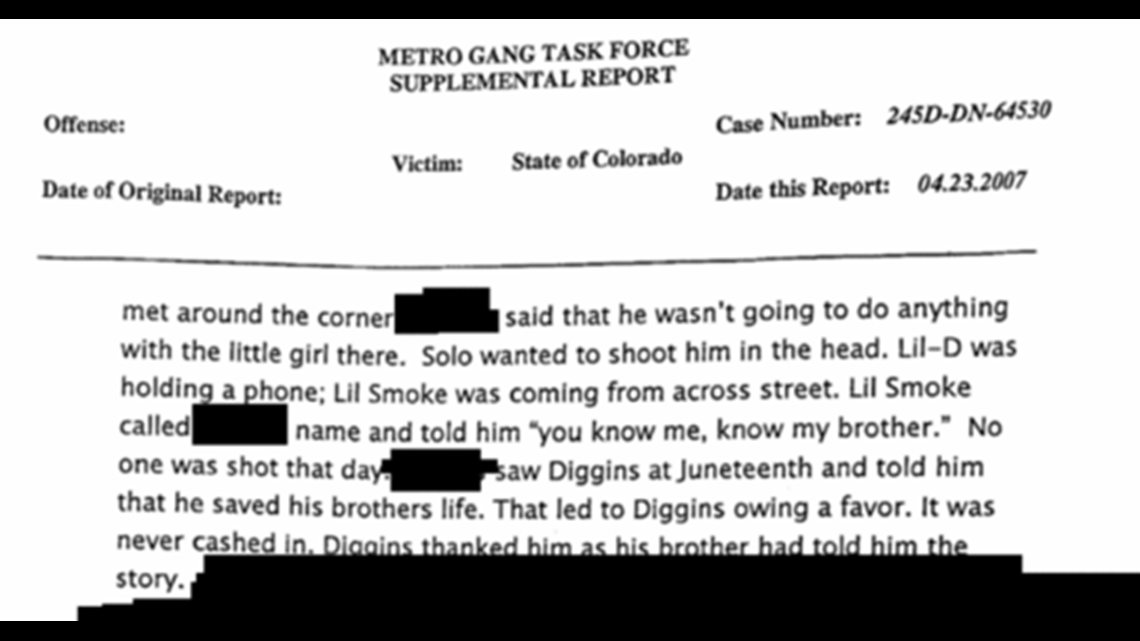

The informant said Diggins’ brother, Erique, known on the streets as Lil’ Smoke, who has a history of arrests ranging from homicide to possession of dangerous drugs and two felony convictions for possession of illegal drugs, was a rival to Hicks, the leader of the Elite Eight. That supposedly gave the gang leverage over Elias Diggins. the informant claimed, according to records reviewed by The Gazette. Diggins, then a captain at the sheriff’s office, was indebted to the gang because Hicks allowed Diggins’ brother, Erique, to walk free one night instead of assassinating him when the two came face to face at a local shop shortly after a flare-up of gang violence, the informant said.

Word of that favor later was passed on to Elias Diggins during a chance encounter at a Juneteenth celebration, the informant said.

The informant told authorities that while Diggins’ debt was never paid in full, Elias Diggins later assisted Hicks, when Hicks was incarcerated at the Denver jail. The informant said Diggins allowed Hicks to make telephone calls on a desk phone at the Sheriff’s Department, a coveted favor since the calls from that phone were not recorded like the collect calls from the phone inmates were supposed to use.

The use of the unsecured telephone allowed Hicks to communicate with his enforcer in the gang without the normal monitoring of such phone calls by law enforcement, the informant said.

One of the deputies the informant claimed had expressed concern about the telephone calls was Eric Hall, who said in an interview that he did not recall them, though Hall said he might have forgotten that they occurred. Another deputy identified by the informant as expressing concern could not be reached for comment.

IV.

Diggins categorically denies these allegations. When questioned in a telephone interview about Hicks and the Elite Eight and the allegations that he let Hicks use an unsecured telephone at the jail, Diggins said: "I'm sorry, I let who do that?" Questioned further, he said: "I don't know what you're talking about." He directed any further questions to the spokesperson at the Denver Sheriff's Department.

In response to follow-up questions, Daria Serna, the spokesperson, said Diggins actually does know Hicks, having met him “in the course and scope of his duties” when Hicks was incarcerated at the Denver County Jail. She denied that Diggins had been told his brother had clashed with the gang and been spared. She said Diggins denies ever letting Hicks use an unsecured phone and added that Diggins did not know Hicks prior to his incarceration.

“There is no merit to any of the claims,” Serna added but confirmed that Diggins has known his brother is a gang member.

"Sheriff Diggins has known that his brother has been affiliated with a gang for over 25 years, and he has never hidden that unfortunate fact," Serna said. "Our life experiences shape who we are and our core personal and professional values. Sheriff Diggins deeply understands the challenges faced by family members who have loved ones in custody and that understanding has shaped his views on compassionate incarceration. Sheriff Diggins continues to work on ways that family members and friends can still maintain connections with people in his custody while protecting the community."

She continued: "To be clear, the choices made by the sheriffs' brother have never compromised the sheriff nor influenced him to make improper or unethical decisions. Sheriff Diggins' passion for treating everyone with dignity and humanity is rooted in his personal understanding of the challenges faced by the loved ones of people who choose this path in life."

When Mayor Hancock named Diggins as sheriff, he said he wanted someone who “genuinely understood the job day in and day out” and noted that Diggins was “someone who appreciates the value of second chances.”

In 1996, Diggins was charged with a felony for attempting to influence a public servant. He admitted to lying to a judge about an insurance issue following a car crash. Diggins pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge.

Diggins, in statements to the press since his appointment as sheriff, has said he wants the department to “re-earn trust that has been broken” following excessive force cases that resulted in multi-million dollar payouts to settle lawsuits.

“We’ve had a lot of challenges that have happened in the past, but it’s a new day,” he said in one recent interview with Denver Urban Spectrum, a monthly newspaper. “It’s a new day for us, and we are going in a direction that I believe is going to be something that the community eventually has trust in us again, and they will see that our actions speak louder than our words.”

But Swift, Ryder, Hall and Schaefer, the former sheriff's department employees, said they question whether Diggins is the person to lead the department because they fear he is too close to gang members.

"When I heard that he was named sheriff, that sent a chill down my spine," said Schaefer, who said he has concerns even though Diggins had been good for Schaefer's career and been an advocate for him at the department.

Schaefer said his concerns stem from how Diggins interacted with Willie Clark when Clark was incarcerated at the Denver County Jail, awaiting trials in a murder-for-hire scheme and in the drive-by slaying of Darrent Williams. Diggins regularly violated department protocol in his interactions with Clark, Schaefer said. Clark had been placed in an isolation cell, cordoned off from other inmates, Schaefer recalled. He said the Sheriff's Department had put in rules that required personnel to refrain from visiting Clark alone without backup.

The protocol requiring the presence of at least two department employees when interacting with Clark was meant to ensure nothing compromising occurred and to protect deputies from the potential that Clark would try to blackmail them, he recalled.

Schaefer said Diggins regularly flouted that rule, telling deputies he was going back to visit Clark alone, hours at a time, and instructing them not to interrupt him when he did so.

"He kept going back there and talking for long periods of time," Schaefer said. "We all thought it was inappropriate."

"It was commonly known at the facility, and it was commonly known with officers and it was commonly known with inmates that he had gang connections," Schaefer said.

Diggins, who was a major back then, denied through the spokesperson that any protocol had been put in place restraining him from interacting alone with Clark. "He did not know Willie Clark and as part of Major Diggins' normal duties he would walk the jail and talk to those in custody while fielding complaints and concerns," the spokesperson said.

Eric Hall said that he witnessed Diggins violate protocol when Diggins' brother, Erique, was incarcerated at the county jail, waiting to be transferred to another jurisdiction on a homicide charge, later dismissed. Hall recalled that he saw Diggins deliver a brown paper bag with unknown material up to his brother's cell. That act violated the department's requirement that all deliveries to inmates go through the mail room to protect against delivery of contraband or weapons, Hall said. Hall said that when he was an investigator in internal affairs he saw other deputies fired for similar behavior.

"There was nothing I could do about it because at that time he had rank over me," Hall said. "But an officer is not allowed to give an inmate anything. Period."

Serna, the department's spokesperson, categorically denied Hall's allegation, saying Diggins "never delivered anything to his brother anytime that he was incarcerated."

V.

Swift and Ryder said they still have concerns about Diggins' loyalties in part because during the trial of Clark, Diggins was seen hugging and fist-bumping Clark's family members and associates at the courthouse. That incident so concerned the head of the U.S. Marshals Service in Denver, who witnessed the display of camaraderie along with Ryder, that Ryder recalled the head marshal turned to him and asked, "Is Elias Diggins a gang member?" Ryder recalled he answered, "No, but he's deeply affiliated with them."

Asked about this incident, Diggins, through the department spokesperson, said he has no knowledge of concerns that other law enforcement agencies have been reluctant to share information on gangs with the sheriff's department and does not recall the described interactions with Clark's family during Clark's trial.

Ryder and Swift said they earned the ire of Diggins by expressing their concerns to others at the department. Swift said that word was passed to Diggins that Swift had questioned his display of affection during the trial. Swift said he had pointed out to a deputy that he wouldn't have hugged and fist-bumped the family and associates of Ku Klux Klan members being tried for murder if he had grown up in the South and known them.

Swift and Ryder both said Diggins berated them separately. Swift said Diggins suspended him from the gang task force for six months and threatened to have the Denver District Attorney's office investigate him, which never occurred. Ryder said Diggins redeployed him to the downtown jail, away from the gang unit. Records show the city asked a human resources consulting firm, then known as Mountain States Employers Council, to investigate after it was alleged Swift made defamatory comments about Diggins and had been insubordinate to Diggins. Swift said Mountain States required him to attend a mediation session with Diggins.

Serna, the spokesperson for the sheriff's department, said that 10 years ago a workplace dispute between Diggins and Swift was resolved through mediation. "Sheriff Diggins recalls the mediation was settled amicably," she said.

Swift, a former internal affairs investigator at the sheriff's department, said he believes internal affairs investigations into allegations of gang ties at the sheriff's department have stalled in part because in the past the Sheriff's Department has been viewed as reluctant to root out wrongdoing and also because top leaders at the department favored Diggins.

"People and outside agencies were reluctant to share things with the department because of failures in previous investigations," said Swift, stressing in particular a reluctance to put confidential informants at risk by disclosing their identity. "There was a belief that things would not be held in confidence. There was a fear that sharing information during active cases would hinder those cases or accusations. That's what I was told from people outside the department."

Bronson, the city attorney, stoutly defended Diggins in her statement. She said that when the controversy over Swift's comments surfaced, the city attorney's office "was asked to retain an outside investigator back in 2010, and based on our review, found no evidence to support the allegations." Asked for a copy of the report from Mountain States Employer Council, Bronson declined to provide it.

"The allegations against Elias Diggins are nothing more than old conspiracy theories," Bronson said in her statement. "It is telling that not a single law enforcement agency involved — not the District Attorney, not the FBI, not the (Denver Sheriff's Department Internal Affairs unit), not the Denver Police Department — found them sufficiently credible to pursue any further."

Swift and Ryder said the only investigation that's ever been conducted as far as they know was on Swift for alleged insubordination for raising his concerns to others at the Sheriff's Department about Diggins.

VI.

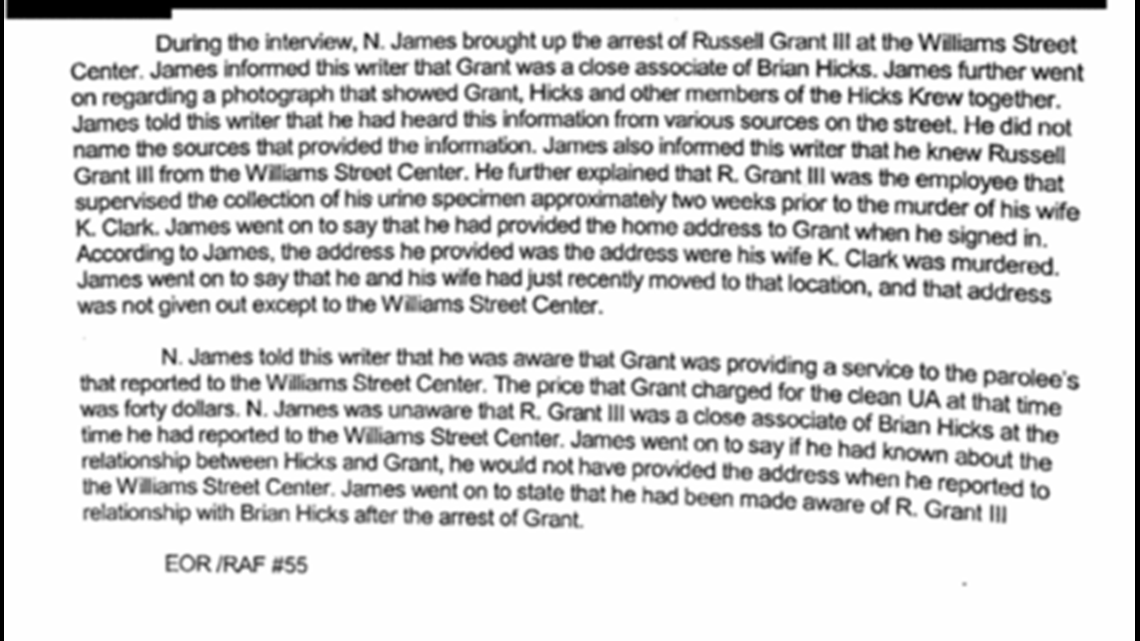

The informant also identified a fifth official, Russell Grant III, a halfway house corrections worker at the Williams Street Center in Denver, as having corruptly assisted the gang and of helping Brian Hicks, the gang’s leader, once administer a pistol-whipping to a rival. After growing suspicious about Grant due to complaints, law enforcement officials reached out to the informant who detailed Grant’s alleged ties to the Elite Eight, which were further confirmed through photos.

Grant did not respond to messages seeking comment.

Grant was arrested after a successful sting operation by law enforcement officials in which he accepted $180 to swap out his urine for that of an undercover police officer’s urine who was wearing a wire and posing as a parolee. Grant, then 32, and also a code enforcement officer for the city of Aurora, pleaded guilty to attempting to influence a public servant and was sentenced to probation. Records show he had been accepting cash to provide clean urine so gang members serving time in a halfway house would pass their drug tests

Records show law enforcement officials suspected Grant may have given a member of the gang the address of Kalonniann Clark, a witness who was later slain at her home. Clark’s live-in boyfriend was on parole at the time of the murder and told police he had given his address to Grant when Grant administered his drug tests at the halfway house and believed Grant had passed the address on to the gang. He said the gang’s members had previously not been able to locate him and his girlfriend, Clark, because they had just moved and had kept their new location secret.

Grant denied providing Clark’s address to the gang during interviews with the police, but a polygraph exam indicated he was being deceptive. He later admitted to police that he told another member of the gang about administering drug tests to Clark’s boyfriend at the halfway house, records show.

A person with ties to law enforcement familiar with the details of Grant's prosecution said Grant was never prosecuted for any complicity in the murder because he only admitted to telling the gang that he was administering drug tests to Clark's boyfriend and denied giving out his address. Without any further confirmation, there was not sufficient evidence to prosecute him for deeper involvement, said the person familiar with the details of the case.

The Elite Eight gang, a subset of the Rolling 30’s Crips and Tre-Tre Crips, was responsible for at least 11 murders and had ties to Mafia crime families, including the Gambinos in New York and the Camorra organized crime syndicate in Sicily, gang intelligence reports show. A cartel led by Mexican drug lord Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman-Lorea supplied the Elite Eight with cocaine, records state. Monthly crack cocaine sales of the gang exceeded $1 million at the gang’s height, according to law enforcement documents.

The Gazette obtained details of the informant's statements through official Metro Gang Task Force summaries, Denver District Attorney records and FBI memorandums of interviews with the informant conducted in 2006, 2007, 2008, 2010 and 2015. Participating in the interviews of the informant were two FBI agents, a federal prosecutor and two local law-enforcement Metro Gang Task Force members.

The informant, a founding member of the gang, helped law enforcement dismantle the Elite Eight by providing details about the gang’s formation, hierarchy, drug trade and murders. He has continued to assist law enforcement as an informant through the years, as recently as 2015 providing information on gang activity in Denver.

Several of the statements from the informant were made during a proffer session in the presence of a federal prosecutor. During such sessions, a witness can divulge criminal activity and potential evidence to prosecutors with the assurance that information cannot be used to prosecute the witness. In such sessions, informants are warned that all statements must be truthful and that untruthful statements can result in prosecution. Colloquially known as becoming “Queen for a Day,” such sessions allow informants to provide helpful information to law enforcement with the hopes of reducing their own prison sentences.

Two law enforcement officials later asked a U.S. District judge to reduce the informant’s prison sentence for assisting in the prosecution of gang members, and the judge agreed to a reduction. The informant has since moved out of state.

VII.

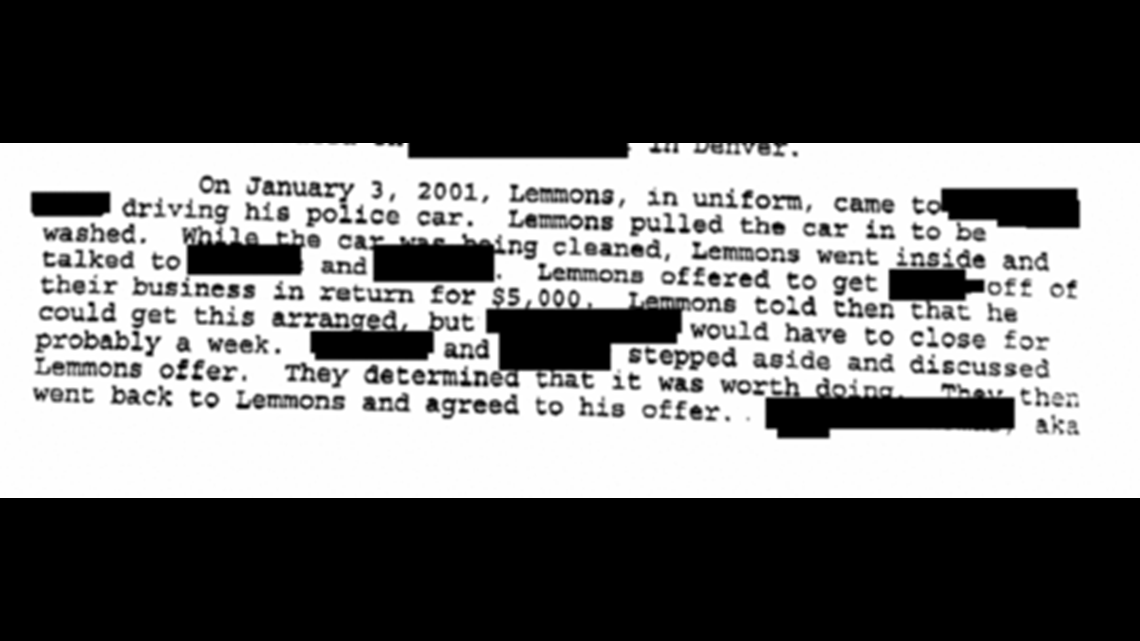

The informant also identified Denver police officer Michael Lemmons as taking $800 from gang members in exchange for promising to alert the gang “when heat was coming down.” The informant further told federal investigators that Lemmons negotiated another $5,000 payment for information, but that deal was never consummated because of an unrelated arrest.

The informant said Lemmons and another Denver police officer, Michael Hall, often worked off-duty shifts providing security at a restaurant in Denver the gang favored, and that when they worked those shifts they allowed individuals to deal drugs out of the restaurant. The informant said those police officers also helped the gang by providing its members several bulletproof vests.

Lemmons denied the informant’s allegations in an interview with The Gazette. He said he had been approached by a member of the gang who tried to bribe him into alerting the gang when police would bust a Denver car wash that was a known spot for drug trafficking. He said he never accepted the cash but played along with hopes of eventually snaring the gang in a sting operation that never came to fruition.

“It sounds like this is coming from someone who is in trouble and trying to save themselves,” he said of the informant’s statements.

Summaries of internal affairs files for all of the individuals named by the informant, obtained through an open records request, do not indicate any internal affairs investigation into the informant's allegations. The summaries do show other issues were raised, some of which occurred at the same restaurant where the informant claimed gang members allegedly bonded with two police officers.

The internal affairs summaries show Lemmons and Hall worked off-duty at that restaurant from 1997 through 2003. According to the summaries, patrons of that restaurant complained the two officers on separate occasions had refused to investigate or provide enforcement action after being alerted of assaults and minor thefts, including one instance when Hall allegedly stated, “I’m not doing nothing to my boy!” An internal affairs investigation exonerated Hall of one of those allegations, but in another instance he received a minor suspension from work duties for failing to follow secondary employment procedures related to working at that restaurant.

Hall retired from the force in 2006 after an investigation disclosed the detective "allegedly committed policy violations." Lemmons was accused of owning a house where “there is drug activity going on,” and of “receiving preferential treatment.” That allegation was not investigated, according to the summary of internal affairs files.

Mitch Morrissey, who was Denver District attorney at the time of the informant’s allegations, said he recalled rumblings that sheriff’s officials, including Diggins, had been accused of exhibiting favoritism toward incarcerated gang members back in 2007, but said he does not recall that a case was ever presented to him for prosecution. He added that such cases are difficult because informants can be prone to embellishment and often have track records that can call their motives into question.

“It’s tough to build a case off of that,” said Morrissey, adding that further complicating the issue were past histories that made it difficult to decipher whether crimes actually occurred or whether the allegations were speculative and based on untruthful lore.

“Some of those guys grew up together and live in the same neighborhood and same communities,” Morrissey said. “They go to the same high schools and the same churches. That makes it hard sometimes to know what’s what.”

A six-year joint federal and local law enforcement investigation into the Elite Eight, and its parent organizations, the Rolling 30’s Crips and the Tre-Tre Crips, resulted in the convictions of more than 70 defendants, including Hicks, who was sentenced to life in prison without parole plus 120 years for soliciting two other gang members to kill Kalonniann Clark.

The 28-year-old Clark was killed on December 6, 2006. At the time of the slaying, she was scheduled to testify that Hicks tried to shoot her in 2005. Hicks was convicted of hiring Shun Birch and Willie Clark, who was convicted of murdering Darrent Williams, to murder Kalonniann Clark.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Investigations from 9Wants to Know